Single-variable calculus can be divided up into differential calculus and integral calculus. Differential calculus studies derivatives and their applications. Integral calculus studies integrals and their applications. The two parts are connected by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus; it says, roughly, that derivatives and integrals are "opposites".

I'll begin this discussion of derivatives with a geometric question.

Given a function ![]() , how do you find the slope of the

tangent line to the graph at the point

, how do you find the slope of the

tangent line to the graph at the point ![]() ?

?

(I'm thinking of the tangent line as a line

that just skims the graph at ![]() , without going

through the graph at that point. This is a vague description, but it

will do for now.)

, without going

through the graph at that point. This is a vague description, but it

will do for now.)

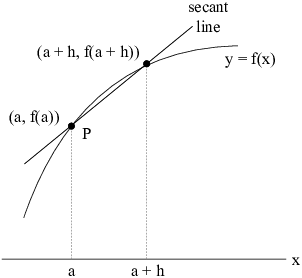

Here's the idea. Pick a point ![]() nearby, and draw

the line connecting

nearby, and draw

the line connecting ![]() to

to ![]() . (A

line connecting two points on a graph is called a

secant line.)

. (A

line connecting two points on a graph is called a

secant line.)

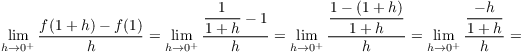

Thus, h represents how much you "moved over" in the x-direction. The line has slope

![]()

If you slide the second point ![]() along the graph

toward P, the secant line gets closer and closer to the tangent line.

Algebraically, this amounts to taking the limit as

along the graph

toward P, the secant line gets closer and closer to the tangent line.

Algebraically, this amounts to taking the limit as ![]() . Thus, the slope of the tangent at

. Thus, the slope of the tangent at ![]() is

is

![]()

Example. Let ![]() .

.

(a) Find the slope of the secant line joining ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

(b) Find the slope of the tangent line to ![]() at

at ![]() .

.

(a)

![]()

(b) In this case, I let ![]() in the equation for

in the equation for ![]() and compute the limit:

and compute the limit:

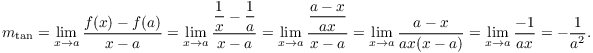

![]()

Another form of the tangent line formula is

![]()

You can get this formula from the previous one by letting ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , so

, so ![]() gives

gives ![]() .

.

Example. Find the slope of the tangent line to

![]() at

at ![]() .

.

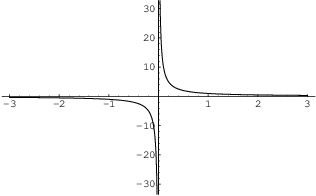

The graph of ![]() is a rectangular hyperbola. Notice

that by not plugging in a specific number for a, I've obtained a

formula which I can use for any a. For example, the slope of the

tangent at

is a rectangular hyperbola. Notice

that by not plugging in a specific number for a, I've obtained a

formula which I can use for any a. For example, the slope of the

tangent at ![]() (i.e. at the point

(i.e. at the point ![]() ) is

) is

![]()

There is another interpretation of the slopes of the secant line and

the tangent line. The slope of the secant line joining ![]() to

to ![]() is

is

![]()

This is the change in f divided by the change in x,

so it represents the average rate of change of

f as x goes from a to b (i.e. on the interval ![]() ).

).

What is the slope of the tangent line at a? It represents the instantaneous rate of change at ![]() . (Sometimes people get lazy and just say "rate

of change" to mean "instantaneous rate of

change".)

. (Sometimes people get lazy and just say "rate

of change" to mean "instantaneous rate of

change".)

Example. Let ![]()

(a) Find the average rate of change of ![]() on the interval

on the interval ![]() .

.

(b) Find the instantaneous rate of change of ![]() at

at ![]() .

.

(a)

![]()

(b) The instantaneous rate of change of ![]() at

at ![]() is

is ![]() at

at ![]() . I'll use the

second formula for

. I'll use the

second formula for ![]() :

:

![]()

I set ![]() and compute the limit:

and compute the limit:

![]()

![]()

Thus, the instantaneous rate of change of ![]() at

at ![]() is

is ![]() . This means

that if f continued to change at the same rate, then for every 4

units that x increased, the function would increase by 1 unit.

. This means

that if f continued to change at the same rate, then for every 4

units that x increased, the function would increase by 1 unit.

Of course, the function does not continue to change at the

same rate. In fact, the rate of change of the function changes! ---

the rate of change of the function is a function itself.![]()

Suppose that the function under investigation gives the position of an object moving in one dimension.

(Think of something moving left or right along the x-axis, or an

object that is thrown straight upward, and which eventually falls

back to earth.) For instance, suppose that ![]() is the position of the object at time t.

is the position of the object at time t.

The average velocity of the object from ![]() to

to ![]() is the change in position divided

by the time elapsed:

is the change in position divided

by the time elapsed:

![]()

Notice that this is the same as the slope of the secant line to the curve, or the average rate of change.

The instantaneous velocity at ![]() is

is

![]()

This is the slope of the tangent line to the curve, or the instantaneous rate of change. You can also use the second formula

![]()

Roughly speaking, the instantaneous velocity measures how fast the object is travelling at a particular instant.

Example. The position of an object at time t is

![]()

(a) Find the average velocity from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

(b) Find the average velocity from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

(c) Find the instantaneous velocity when ![]() .

.

(a)

![]()

(b)

![]()

What does this mean? Notice that ![]() and

and ![]() . In other words, the object moved around from

. In other words, the object moved around from ![]() to

to ![]() , but it wound up back where it

started. Since the net change in position was 0, the average

velocity was 0.

, but it wound up back where it

started. Since the net change in position was 0, the average

velocity was 0.![]()

(c) I set ![]() in

in

![]()

I get

![]()

People who have seen calculus before know that ![]() is usually called the

derivative of

is usually called the

derivative of ![]() at a. It is denoted by

at a. It is denoted by

![]()

That is, the derivative of ![]() at

at ![]() is given by

is given by

![]()

![]() gives the instantaneous rate of change of f at a, or

the slope of the tangent line to the graph of

gives the instantaneous rate of change of f at a, or

the slope of the tangent line to the graph of ![]() at

at ![]() .

.

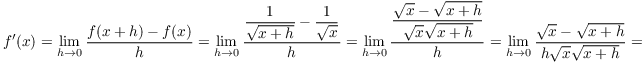

The derivative is a function in its own right. Since x is usually used to denote the input variable for a function, it's common to write the definition of the derivative in this form:

![]()

f is differentiable at x if ![]() exists --- that is, if the limit above is defined.

exists --- that is, if the limit above is defined.

Example. Compute ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

Example. Suppose

![]()

Is f differentiable at ![]() ?

?

![]()

However, the definition of ![]() depends on whether h is

positive or negative. I need to take the left- and right-hand limits

at 1.

depends on whether h is

positive or negative. I need to take the left- and right-hand limits

at 1.

The right-hand limit is

![]()

The left-hand limit is

![]()

Since the left- and right-hand limits agree, the two-sided limit exists. Thus,

![]()

This shows that f is differentiable at ![]() .

.

In this example, the function was constructed by "gluing"

the two pieces ![]() and

and ![]() together at

together at

![]() . The fact that

. The fact that ![]() was defined means

that the pieces were "glued together smoothly". By analogy,

if the two pieces of the function are like two pieces of wood being

glued together, you could run your hand over the joint and not feel a

"corner" or "ridge".

was defined means

that the pieces were "glued together smoothly". By analogy,

if the two pieces of the function are like two pieces of wood being

glued together, you could run your hand over the joint and not feel a

"corner" or "ridge".![]()

Geometrically, a differentiable function has a tangent line at each point of its graph. You'd suspect that this would rule out gaps, jumps, or vertical asymptotes --- typical discontinuities. In fact, the requirement that a differentiable function have a tangent line at each point means that its graph has no "corners" --- all of the curves and turns are "smooth".

Theorem. A differentiable function is continuous.

Proof. Suppose ![]() is differentiable at

a point c. By definition,

is differentiable at

a point c. By definition,

![]()

Then

![]()

On the one hand, ![]() , so

the left side is 0. On the other hand, the product of the limits is

the limit of the product, so

, so

the left side is 0. On the other hand, the product of the limits is

the limit of the product, so

![]()

I can rewrite this as

![]()

This says that f is continuous at c.![]()

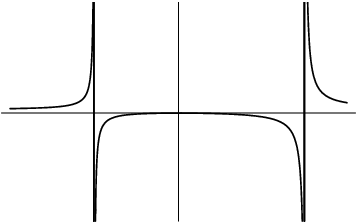

Example. The picture below shows that graph of

a function ![]() . Sketch the graph of

. Sketch the graph of ![]() .

.

I'll do each piece separately from left to right. The left hand piece starts out with a small positive slope. The slope increases till it is large and positive at the asymptote.

The piece in the middle starts out with a big positive slope at the left-hand asymptote. It decreases to 0 --- there's a horizontal tangent at the top of the "bump". It continues to decrease, becoming big and negative at the right-hand asymptote.

Finally, the right-hand piece starts out with a big negative slope near the asymptote. As you go out to the right, the slope continues to be negative, but the curve flattens out --- that is, the slope approaches 0.

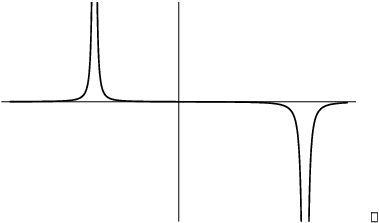

Putting these observations together produces a picture like this:

The preceding discussion suggests the following rule of thumb: If a graph is continuous at a point but has a "corner" there, the derivative at the corner is undefined.

This is not the only way the derivative can be undefined: For example, the derivative is undefined at a point where the graph has a vertical tangent line.

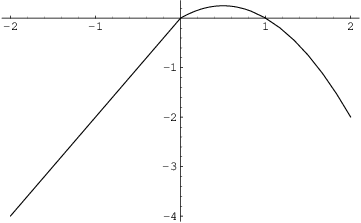

Example. Suppose

![]()

Tell whether there is a corner in the graph at ![]() by computing the derivative at 0.

by computing the derivative at 0.

The derivative is

![]()

(I used the fact that ![]() .)

.)

Since f is defined in two pieces, I have to compute the limit on the left and right:

![]()

![]()

The left- and right-hand limits do not agree. Therefore, the

two-sided limit ![]() is undefined --- f is not differentiable at

is undefined --- f is not differentiable at

![]() .

.

The left- and right-hand limits I computed are sometimes called the

left- and right-hand derivatives of f at ![]() . Intuitively, they give the slope of the tangent as

you come in from the left and right, respectively. Thus, the

left-hand derivative at 0 is 2 and the right-hand derivative at 0 is

1.

. Intuitively, they give the slope of the tangent as

you come in from the left and right, respectively. Thus, the

left-hand derivative at 0 is 2 and the right-hand derivative at 0 is

1.![]()

Copyright 2018 by Bruce Ikenaga