Definition. Let V be a vector space over F,

where ![]() or

or ![]() . An inner product on V is a function

. An inner product on V is a function ![]() which satisfies:

which satisfies:

(a) (Linearity) ![]() ,

for

,

for ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

(b) (Symmetry) ![]() ,for

,for ![]() . ("

. ("![]() " denotes

the complex conjugate of x.)

" denotes

the complex conjugate of x.)

(c) (Positive-definiteness) If ![]() , then

, then ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

A vector space with an inner product is an inner

product space. If ![]() , V is a

real inner product space; if

, V is a

real inner product space; if ![]() , V is a complex inner product space.

, V is a complex inner product space.

Notation. There are various notations for

inner products. You may see "![]() " or

"

" or

"![]() " or "

" or "![]() ", for

instance. Some specific inner products come with established

notation. For example, the dot product, which

I'll discuss below, is denoted "

", for

instance. Some specific inner products come with established

notation. For example, the dot product, which

I'll discuss below, is denoted "![]() ".

".

Proposition. Let V be an inner product space

over F, where ![]() or

or ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() , and let

, and let ![]() .

.

(a) ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() .

.

In particular, if ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

(c) If ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

(a)

![]()

By symmetry, ![]() as well.

as well.

(b)

![]()

If ![]() , then

, then ![]() , and so

, and so

![]() .

.

(c) As in the proof of (b), I have ![]() , so

, so

![]()

Remarks. Why include complex conjugation in the symmetry axiom? Suppose the symmetry axiom had read

![]()

Then

![]()

This contradicts ![]() . That is, I can't have

both pure symmetry and positive definiteness.

. That is, I can't have

both pure symmetry and positive definiteness.![]()

Example. Suppose u, v, and w are vectors in a real inner product space V. Suppose

![]()

![]()

(a) Compute ![]() .

.

(b) Compute ![]() .

.

(a) Using the linearity and symmetry properties, I have

![]()

![]()

Notice that this "looks like" the polynomial multiplication you learned in basic algebra:

![]()

(b)

![]()

Example. Let ![]() . The dot product on

. The dot product on

![]() is given by

is given by

![]()

It's easy to verify that the axioms for an inner product hold. For

example, suppose ![]() . Then at

least one of

. Then at

least one of ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() is nonzero, so

is nonzero, so

![]()

This proves that the dot product is positive-definite.![]()

I can use an inner product to define lengths and angles. Thus, an inner product introduces (metric) geometry into vector spaces.

Definition. Let V be an inner product space,

and let ![]() .

.

(a) The length of x is ![]() .

.

(b) The distance between x and y is ![]() .

.

(c) The angle between x and y is the smallest

positive real number ![]() satisfying

satisfying

![]()

Remark. The definition of the angle between x and y wouldn't make sense if the

expression ![]() was greater than 1 or less than -1, since I'm

asserting that it's the cosine of an angle.

was greater than 1 or less than -1, since I'm

asserting that it's the cosine of an angle.

In fact, the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality (which I'll prove below) will show that

![]()

Proposition. Let V be a real inner product

space, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

(a) ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() . ("

. ("![]() " denotes the absolute value of a.)

" denotes the absolute value of a.)

(c) ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() .

.

(d) ( Cauchy- Schwarz inequality) ![]() .

.

(e) ( Triangle inequality) ![]() .

.

Proof. (a) Squaring ![]() gives

gives ![]() .

.

(b) Since ![]() ,

,

![]()

(c) ![]() implies

implies ![]() , and

hence

, and

hence ![]() . Conversely, if

. Conversely, if ![]() , then

, then ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

(d) If ![]() , then

, then

![]()

Hence, ![]() . The same is true

if

. The same is true

if ![]() .

.

Thus, I may assume that ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The major part of the proof comes next, and it involves a trick. Don't feel bad if you wouldn't have thought of this yourself: Try to follow along and understand the steps.

If ![]() , then by positive-definiteness and

linearity,

, then by positive-definiteness and

linearity,

![]()

The trick is to pick "nice" values for a and b. I will set

![]() and

and ![]() . (A rationale for this is that I

want the expression

. (A rationale for this is that I

want the expression ![]() to appear in the

inequality.)

to appear in the

inequality.)

I get

Since ![]() and

and ![]() , I have

, I have ![]() and

and ![]() . So I can divide the

inequality by

. So I can divide the

inequality by ![]() to obtain

to obtain

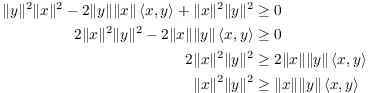

![]()

In the last inequality, x and y are arbitrary vectors. So the

inequality is still true if x is replaced by ![]() . If I replace x with

. If I replace x with ![]() , then

, then ![]() and

and ![]() , and the inequality becomes

, and the inequality becomes

![]()

Since ![]() is greater than or equal to both

is greater than or equal to both ![]() and

and ![]() , I have

, I have

![]()

(e)

![]()

Hence, ![]() .

.![]()

Example. ![]() is an inner

product space using the standard dot product of vectors. The cosine

of the angle between

is an inner

product space using the standard dot product of vectors. The cosine

of the angle between ![]() and

and ![]() is

is

![]()

Example. Let ![]() denote the real vector space of continuous functions

on the interval

denote the real vector space of continuous functions

on the interval ![]() . Define an inner product on

. Define an inner product on ![]() by

by

![]()

Note that ![]() is integrable, since it's continuous on a

closed interval.

is integrable, since it's continuous on a

closed interval.

The verification that this gives an inner product relies on standard

properties of Riemann integrals. For example, if ![]() ,

,

![]()

Given that this is a real inner product, I may apply the preceding proposition to produce some useful results. For example, the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality says that

![]()

Definition. A set of vectors S in an inner

product space V is orthogonal if ![]() for

for ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

An orthogonal set S is orthonormal if ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.

If you've seen dot products in a multivariable calculus course, you

know that vectors in ![]() whose dot product is 0 are

perpendicular. With this interpretation, the vectors in an orthogonal

set are mutually perpendicular. The vectors in an orthonormal set are

mutually perpendicular unit vectors.

whose dot product is 0 are

perpendicular. With this interpretation, the vectors in an orthogonal

set are mutually perpendicular. The vectors in an orthonormal set are

mutually perpendicular unit vectors.

Notation. If I is an index set, the Kronecker delta ![]() (or

(or ![]() ) is defined by

) is defined by

![]()

With this notation, a set ![]() is orthonormal if

is orthonormal if

![]()

Note that the ![]() matrix whose

matrix whose ![]() -th component is

-th component is ![]() is the

is the ![]() identity matrix.

identity matrix.

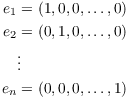

Example. The standard basis for ![]() is

is

It's clear that relative to the dot product on ![]() , each of these vectors as length 1, and each pair of

the vectors has dot product 0. Hence, the standard basis is an

orthonormal set relative to the dot product on

, each of these vectors as length 1, and each pair of

the vectors has dot product 0. Hence, the standard basis is an

orthonormal set relative to the dot product on ![]() .

.![]()

Example. Consider the following set of

vectors in ![]() :

:

![]()

I have

![]()

![]()

![]()

It follows that the set is orthonormal relative to the dot product on

![]() .

.![]()

Example. Let ![]() denote the complex-valued continuous

functions on

denote the complex-valued continuous

functions on ![]() . Define an inner product by

. Define an inner product by

![]()

Let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

It follows that the following set is orthonormal in ![]() relative to this inner product:

relative to this inner product:

![]()

Proposition. Let ![]() be an orthogonal set of vectors,

be an orthogonal set of vectors, ![]() for all i. Then

for all i. Then ![]() is independent.

is independent.

Proof. Suppose

![]()

Take the inner product of both sides with ![]() :

:

![]()

Since ![]() is orthogonal,

is orthogonal,

![]()

The equation becomes

![]()

But ![]() by positive-definiteness,

since

by positive-definiteness,

since ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() .

.

Similarly, taking the inner product of both sides of the original

equation with ![]() , ...

, ... ![]() shows

shows ![]() for all j. Therefore,

for all j. Therefore, ![]() is independent.

is independent.![]()

An orthonormal set consists of vectors of length 1, so the vectors are obviously nonzero. Hence, an orthonormal set is independent, and forms a basis for the subspace it spans. A basis which is an orthonormal set is called an orthonormal basis.

It is very easy to find the components of a vector relative to an orthonormal basis.

Proposition. Let ![]() be an orthonormal basis for V, and let

be an orthonormal basis for V, and let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Note: In fact, the sum above is a finite sum --- that is, only finitely many terms are nonzero.

Proof. Since ![]() is a basis, there are elements

is a basis, there are elements ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that

![]()

Take the inner product of both sides with ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

As in the proof of the last proposition, all the inner product terms

on the right vanish, except that ![]() by orthonormality. Thus,

by orthonormality. Thus,

![]()

Taking the inner product of both sides of the original equation with

![]() , ...

, ... ![]() shows

shows

![]()

Example. Here is an orthonormal basis for

![]() :

:

![$$\left\{ \left[\matrix{\dfrac{3}{5} \cr \noalign{\vskip2pt} \dfrac{4}{5} \cr}\right], \left[\matrix{-\dfrac{4}{5} \cr \noalign{\vskip2pt} \dfrac{3}{5} \cr}\right]\right\}$$](inner-products186.png)

To express ![]() in terms of this basis, take the dot

product of the vector with each element of the basis:

in terms of this basis, take the dot

product of the vector with each element of the basis:

![]()

![]()

Hence,

![$$\left[\matrix{-7 \cr 6 \cr}\right] = \dfrac{3}{5} \cdot \left[\matrix{\dfrac{3}{5} \cr \noalign{\vskip2pt} \dfrac{4}{5} \cr}\right] + \dfrac{46}{5} \cdot \left[\matrix{-\dfrac{4}{5} \cr \noalign{\vskip2pt} \dfrac{3}{5} \cr}\right].\quad\halmos$$](inner-products190.png)

Example. Let ![]() denote the complex inner product space of

complex-valued continuous functions on

denote the complex inner product space of

complex-valued continuous functions on ![]() , where the inner product is defined by

, where the inner product is defined by

![]()

I noted earlier that the following set is orthonormal:

![]()

Suppose I try to compute the "components" of ![]() relative to this orthonormal set by taking inner

products --- that is, using the approach of the preceding example.

relative to this orthonormal set by taking inner

products --- that is, using the approach of the preceding example.

For ![]() ,

,

![]()

Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

There are infinitely many nonzero components! Of course, the reason

this does not contradict the earlier result is that ![]() may not lie in the span of S. S is orthonormal, hence

independent, but it is not a basis for

may not lie in the span of S. S is orthonormal, hence

independent, but it is not a basis for ![]() .

.

In fact, since ![]() , a

finite linear combination of elements of S must be periodic.

, a

finite linear combination of elements of S must be periodic.

It is still reasonable to ask whether (or in what sense) ![]() can be represented by the the infinite sum

can be represented by the the infinite sum

![]()

For example, it is reasonable to ask whether the series converges

uniformly to f at each point of ![]() . The answers

to these kinds of questions would require an excursion into the

theory of Fourier series.

. The answers

to these kinds of questions would require an excursion into the

theory of Fourier series.![]()

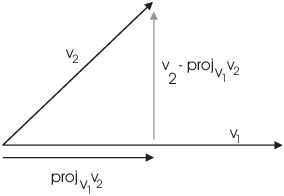

Since it's so easy to find the components of a vector relative to an orthonormal basis, it's of interest to have an algorithm which converts a given basis to an orthonormal one.

The Gram-Schmidt algorithm converts a basis to an orthonormal basis by "straightening out" the vectors one by one.

The picture shows the first step in the straightening process. Given

vectors ![]() and

and ![]() , I want to replace

, I want to replace

![]() with a vector perpendicular to

with a vector perpendicular to ![]() . I can do this by taking the component of

. I can do this by taking the component of ![]() perpendicular to

perpendicular to ![]() , which is

, which is

![]()

Lemma. ( Gram-Schmidt

algorithm) Let ![]() be a set of

nonzero vectors in an inner product space V. Suppose

be a set of

nonzero vectors in an inner product space V. Suppose ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() are pairwise

orthogonal. Let

are pairwise

orthogonal. Let

![]()

Then ![]() is orthogonal to

is orthogonal to ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() .

.

Proof. Let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Now ![]() for

for ![]() because the set is orthogonal. Hence, the right side

collapses to

because the set is orthogonal. Hence, the right side

collapses to

![]()

Suppose that I start with an independent set ![]() . Apply the Gram-Schmidt procedure to the

set, beginning with

. Apply the Gram-Schmidt procedure to the

set, beginning with ![]() . This produces an

orthogonal set

. This produces an

orthogonal set ![]() . In fact,

. In fact, ![]() is a nonzero orthogonal set, so it

is independent as well.

is a nonzero orthogonal set, so it

is independent as well.

To see that each ![]() is nonzero, suppose

is nonzero, suppose

![]()

Then

![]()

This contradicts the independence of ![]() , because

, because ![]() is expressed as the linear combination of

is expressed as the linear combination of ![]() , ...

, ... ![]() .

.

In general, if the algorithm is applied iteratively to a set of vectors, the span is preserved at each state. That is,

![]()

This is true at the start, since ![]() . Assume

inductively that

. Assume

inductively that

![]()

Consider the equation

![]()

It expresses ![]() as a linear combination of

as a linear combination of ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() .

.

Conversely,

![]()

![]()

It follows that ![]() , so

, so ![]() , by induction.

, by induction.

To summarize: If you apply Gram-Schmidt to a set of vectors, the algorithm produces a new set of vectors with the same span as the old set. If the original set was independent, the new set is independent (and orthogonal) as well.

So, for example, if Gram-Schmidt is applied to a basis for an inner product space, it will produce an orthogonal basis for the space.

Finally, you can always produce orthonormal set from a

orthogonal set (of nonzero vectors) --- merely divide each vector in

the orthogonal set by its length.![]()

Example. (

Gram-Schmidt) Apply Gram-Schmidt to the following set of vectors

in ![]() (relative to the usual dot product):

(relative to the usual dot product):

![$$\left\{\left[\matrix{3 \cr 0 \cr 4 \cr}\right], \left[\matrix{-1 \cr 0 \cr 7 \cr}\right], \left[\matrix{2 \cr 9 \cr 11 \cr}\right]\right\}.$$](inner-products249.png)

![]()

![]()

![]()

(A common mistake here is to project onto ![]() ,

, ![]() , ... . I need to project onto the

vectors that have already been orthogonalized. That is why I

projected onto

, ... . I need to project onto the

vectors that have already been orthogonalized. That is why I

projected onto ![]() and

and ![]() rather than

rather than ![]() and

and ![]() .)

.)

The algorithm has produced the following orthogonal set:

![$$\left\{\left[\matrix{3 \cr 0 \cr 4 \cr}\right], \left[\matrix{-4 \cr 0 \cr 3 \cr}\right], \left[\matrix{0 \cr 9 \cr 0 \cr}\right]\right\}.$$](inner-products259.png)

The lengths of these vectors are 5, 5, and 9. For example

![]()

The correponding orthonormal set is

![$$\left\{\dfrac{1}{5}\left[\matrix{3 \cr 0 \cr 4 \cr}\right], \dfrac{1}{5}\left[\matrix{-4 \cr 0 \cr 3 \cr}\right], \left[\matrix{0 \cr 1 \cr 0 \cr}\right]\right\}.\quad\halmos$$](inner-products261.png)

Example. (

Gram-Schmidt) Find an orthonormal basis (relative to the usual

dot product) for the subspace of ![]() spanned by the

vectors

spanned by the

vectors

![]()

I'll use ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() to denote the orthonormal basis.

to denote the orthonormal basis.

To simplify the computations, you should fix the vectors so they're mutually perpendicular first. Then you can divide each by its length to get vectors of length 1.

First,

![]()

Next,

![]()

![]()

You can check that ![]() , so the first two are

perpendicular.

, so the first two are

perpendicular.

Finally,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

If at any point you wind up with a vector with fractions, it's a good idea to clear the fractions before continuing. Since multiplying a vector by a number doesn't change its direction, it remains perpendicular to the vectors already constructed.

Thus, I'll multiply the last vector by 9 and use

![]()

Thus, the orthogonal set is

![]()

The lengths of these vectors are 3, 9, and ![]() . Dividing the vectors by their

lengths gives and orthonormal basis:

. Dividing the vectors by their

lengths gives and orthonormal basis:

![]()

Recall that when an n-dimensional vector is interpreted as a matrix,

it is taken to be an ![]() matrix: that is, an

n-dimensional column vector

matrix: that is, an

n-dimensional column vector

![$$(v_1, v_2, \ldots v_n) = \left[\matrix{v_1 \cr v_2 \cr \vdots \cr v_n \cr}\right].$$](inner-products280.png)

If I need an n-dimensional row vector, I'll take the transpose. Thus,

![]()

Lemma. Let A be an invertible ![]() matrix with entries in

matrix with entries in ![]() . Let

. Let

![]()

Then ![]() defines an inner product on

defines an inner product on ![]() .

.

Proof. I have to check linearity, symmetry, and positive definiteness.

First, if ![]() , then

, then

![]()

This proves that the function is linear in the first slot.

Next,

![]()

The second equality comes from the fact that ![]() for matrices. The third inequality comes

from the fact that

for matrices. The third inequality comes

from the fact that ![]() is a

is a ![]() matrix, so it equals its transpose.

matrix, so it equals its transpose.

This proves that the function is symmetric.

Finally,

![]()

Now ![]() is an

is an ![]() vector --- I'll label its

components this way:

vector --- I'll label its

components this way:

![$$A x = \left[\matrix{u_1 \cr u_2 \cr \vdots \cr u_n \cr}\right].$$](inner-products296.png)

Then

![$$\innp{x}{x} = (A x)^T (A x) = \left[\matrix{u_1 & u_2 & \cdots & u_n \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{u_1 \cr u_2 \cr \vdots \cr u_n \cr}\right] = u_1^2 + u_2^2 + \cdots + u_n^2 \ge 0.$$](inner-products297.png)

That is, the inner product of a vector with itself is a nonnegative

number. All that remains is to show that if the inner product of a

vector with itself is 0, them the vector is ![]() .

.

Using the notation above, suppose

![]()

Then ![]() , because a nonzero u would

produce a positive number on the right side of the equation.

, because a nonzero u would

produce a positive number on the right side of the equation.

So

![$$A x = \left[\matrix{u_1 \cr u_2 \cr \vdots \cr u_n \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{0 \cr 0 \cr \vdots \cr 0 \cr}\right] = \vec{0}.$$](inner-products301.png)

Finally, I'll use the fact that A is invertible:

![]()

This proves that the function is positive definite, so it's an inner

product.![]()

Example. The previous lemma provides lots of

examples of inner products on ![]() besides the usual

dot product. All I have to do is take an invertible matrix A and form

besides the usual

dot product. All I have to do is take an invertible matrix A and form

![]() , defining the inner product as above.

, defining the inner product as above.

For example, this ![]() real matrix is invertible:

real matrix is invertible:

![]()

Now

![]()

(Notice that ![]() will always be symmetric.) The inner

product defined by this matrix is

will always be symmetric.) The inner

product defined by this matrix is

![]()

For example, under this inner product,

![]()

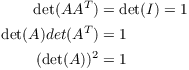

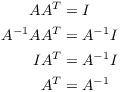

Definition. A matrix A in ![]() is orthogonal if

is orthogonal if ![]() .

.

Proposition. Let A be an orthogonal matrix.

(a) ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() --- in other words,

--- in other words, ![]() .

.

(c) The rows of A form an orthonormal set. The columns of A form an orthonormal set.

(d) A preserves dot products --- and hence, lengths and angles --- in the sense that

![]()

Proof. (a) If A is orthogonal,

Therefore, ![]() .

.

(b) Since ![]() , the determinant is certainly

nonzero, so A is invertible. Hence,

, the determinant is certainly

nonzero, so A is invertible. Hence,

But ![]() , so

, so ![]() as well.

as well.

(c) The equation ![]() implies that the rows of A form an

orthonormal set of vector. Likewise,

implies that the rows of A form an

orthonormal set of vector. Likewise, ![]() shows that the

same is true for the columns of A.

shows that the

same is true for the columns of A.

(d) The ordinary dot product of vectors ![]() and

and ![]() can be written as a matrix

multiplication:

can be written as a matrix

multiplication:

![$$x \cdot y = \left[\matrix{x_1 & x_2 & \cdots & x_n \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{y_1 \cr y_2 \cr \vdots \cr y_n \cr}\right] = x^T y.$$](inner-products327.png)

(Remember the convention that vectors are column vectors.)

Suppose A is orthogonal. Then

![]()

In other words, orthogonal matrices preserve dot products. It follows

that orthogonal matrices will also preserve lengths of

vectors and angles between vectors, because these are

defined in terms of dot products.![]()

Example. Find real numbers a and b such that the following matrix is orthogonal:

![]()

Since the columns of A must form an orthonormal set, I must have

![]()

(Note that ![]() already.) The first equation

gives

already.) The first equation

gives

![]()

The easy way to get a solution is to swap 0.6 and 0.8 and negate one

of them; thus, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , I'm done. (If the a and b I

chose had made

, I'm done. (If the a and b I

chose had made ![]() , then I'd simply divide

, then I'd simply divide ![]() by its length.)

by its length.)![]()

Example. Orthogonal ![]() matrices represent rotations of the

plane about the origin or reflections across a

line through the origin.

matrices represent rotations of the

plane about the origin or reflections across a

line through the origin.

Rotations are represented by matrices

![]()

You can check that this works by considering the effect of

multiplying the standard basis vectors ![]() and

and ![]() by this matrix.

by this matrix.

Multiplying a vector by the following matrix product reflects the

vector across the line L that makes an angle ![]() with the x-axis:

with the x-axis:

![]()

Reading from right to left, the first matrix rotates everything by

![]() radians, so L coincides with the x-axis. The second

matrix reflects everything across the x-axis. The third matrix

rotates everything by

radians, so L coincides with the x-axis. The second

matrix reflects everything across the x-axis. The third matrix

rotates everything by ![]() radians. Hence, a given vector is

rotated by

radians. Hence, a given vector is

rotated by ![]() and reflected across the x-axis, after

which the reflected vector is rotated by

and reflected across the x-axis, after

which the reflected vector is rotated by ![]() . The net effect is to reflect across L.

. The net effect is to reflect across L.

Many transformation problems can be easily accomplished by doing

transformations to reduce a general problem to a special case.![]()

Send comments about this page to: Bruce.Ikenaga@millersville.edu.

Copyright 2014 by Bruce Ikenaga