Recall that the conjugate of a complex number

![]() is

is ![]() . The conjugate of

. The conjugate of ![]() is denoted

is denoted ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

In this section, I'll use ![]() for complex conjugation of numbers of matrices. I

want to use

for complex conjugation of numbers of matrices. I

want to use ![]() to denote

an operation on matrices, the conjugate

transpose.

to denote

an operation on matrices, the conjugate

transpose.

Thus,

![]()

Complex conjugation satisfies the following properties:

(a) If ![]() , then

, then ![]() if and only if z is a real number.

if and only if z is a real number.

(b) If ![]() , then

, then

![]()

(c) If ![]() , then

, then

![]()

The proofs are easy; just write out the complex numbers (e.g. ![]() and

and ![]() ) and compute.

) and compute.

The conjugate of a matrix A is the matrix ![]() obtained by conjugating each

element: That is,

obtained by conjugating each

element: That is,

![]()

You can check that if A and B are matrices and ![]() , then

, then

![]()

You can prove these results by looking at individual elements of the matrices and using the properties of conjugation of numbers given above.

Definition. If A is a complex matrix, ![]() is the conjugate transpose of A:

is the conjugate transpose of A:

![]()

Note that the conjugation and transposition can be done in either

order: That is, ![]() . To see this, consider the

. To see this, consider the ![]() element of the matrices:

element of the matrices:

![]()

Example. If

![$$A = \left[\matrix{ 1 + 2i & 2 - i & 3i \cr 4 & -2 + 7i & 6 + 6i \cr}\right], \quad\hbox{then}\quad A^* = \left[\matrix{ 1 - 2i & 4 \cr 2 + i & -2 - 7i \cr -3i & 6 - 6i \cr}\right].$$](unitary-and-hermitian-matrices26.png)

Since the complex conjugate of a real number is the real number, if B

is a real matrix, then ![]() .

.![]()

Remark. Most people call ![]() the adjoint of A ---

though, unfortunately, the word "adjoint" has already been

used for the transpose of the matrix of cofactors in the determinant

formula for

the adjoint of A ---

though, unfortunately, the word "adjoint" has already been

used for the transpose of the matrix of cofactors in the determinant

formula for ![]() . (Sometimes people

try to get around this by using the term "classical

adjoint" to refer to the transpose of the matrix of cofactors.)

In modern mathematics, the word "adjoint" refers to a

property of

. (Sometimes people

try to get around this by using the term "classical

adjoint" to refer to the transpose of the matrix of cofactors.)

In modern mathematics, the word "adjoint" refers to a

property of ![]() that I'll prove below.

This property generalizes to other things which you might see in more

advanced courses.

that I'll prove below.

This property generalizes to other things which you might see in more

advanced courses.

The ![]() operation

is sometimes called the Hermitian --- but this

has always sounded ugly to me, so I won't use this terminology.

operation

is sometimes called the Hermitian --- but this

has always sounded ugly to me, so I won't use this terminology.

Since this is an introduction to linear algebra, I'll usually refer

to ![]() as the conjugate

transpose, which at least has the virtue of saying what the

thing is.

as the conjugate

transpose, which at least has the virtue of saying what the

thing is.

Proposition. Let U and V be complex

matrices, and let ![]() .

.

(a) ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() .

.

(c) ![]() .

.

(d) If ![]() , their dot product

is given by

, their dot product

is given by

![]()

Proof. I'll prove (a), (c), and (d).

For (a), I use the fact noted above that ![]() and

and ![]() can be

done in either order, along with the facts that

can be

done in either order, along with the facts that

![]()

I have

![]()

This proves (a).

For (c), I have

![]()

For (d), recall that the dot product of complex vectors ![]() and

and ![]() is

is

![]()

Notice that you take the complex conjugates of the components of v before multiplying!

This can be expressed as the matrix multiplication

![$$u \cdot v = \left[\matrix{ \conjugate{v_1} & \conjugate{v_2} & \cdots & \conjugate{v_n} \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{u_1 \cr u_2 \cr \vdots \cr u_n \cr}\right] = v^* u.\quad\halmos$$](unitary-and-hermitian-matrices47.png)

Example. In this example, use the complex dot product.

(a) Compute ![]() .

.

(b) Find ![]() .

.

(c) Find a nonzero vector ![]() which is orthogonal to

which is orthogonal to ![]() .

.

(a)

![]()

It's a common notational abuse to write the number "![]() " instead of writing it as a

" instead of writing it as a ![]() matrix "

matrix "![]() ".

".![]()

(b)

![]()

Hence, ![]() .

.![]()

The following formula is evident from this example:

![]()

This extends in the obvious way to vectors in ![]() .

.

(c) I need

![]()

In matrix form, this is

![]()

Note that the vector ![]() was

conjugated and transposed.

was

conjugated and transposed.

Doing the matrix multiplication,

![]()

I can get a solution ![]() by switching the

numbers

by switching the

numbers ![]() and

and ![]() and negating one of them:

and negating one of them: ![]() .

.![]()

There are two points about the equation ![]() which might be confusing. First,

why is it necessary to conjugate and transpose v? The reason

for the conjugation goes back to the need for inner products to be

positive definite (so

which might be confusing. First,

why is it necessary to conjugate and transpose v? The reason

for the conjugation goes back to the need for inner products to be

positive definite (so ![]() is a nonnegative

real number).

is a nonnegative

real number).

The reason for the transpose is that I'm using the convention that

vectors are column vectors. So if u and v are n-dimensional

column vectors and I want the product to be a number --- i.e. a ![]() matrix --- I have to multiply an

n-dimensional row vector (

matrix --- I have to multiply an

n-dimensional row vector (![]() ) and an n-dimensional column

vector (

) and an n-dimensional column

vector (![]() ). To get the row

vector, I have to transpose the column vector.

). To get the row

vector, I have to transpose the column vector.

Finally, why do u and v switch places in going from the left side to

the right side? The reason you write ![]() instead of

instead of ![]() is because inner products are defined to be

linear in the first variable. If you use

is because inner products are defined to be

linear in the first variable. If you use ![]() you get a product which is linear in the

second variable.

you get a product which is linear in the

second variable.

Of course, none of this makes any difference if you're dealing with

real numbers. So if x and y are vectors in ![]() , you can write

, you can write

![]()

Definition. A complex matrix U is unitary if ![]() .

.

Notice that if U happens to be a real matrix, ![]() , and the equation says

, and the equation says ![]() --- that is, U is orthogonal. In other

words, unitary is the complex analog of orthogonal.

--- that is, U is orthogonal. In other

words, unitary is the complex analog of orthogonal.

By the same kind of argument I gave for orthogonal matrices, ![]() implies

implies ![]() --- that is,

--- that is, ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Proposition. Let U be a unitary matrix.

(a) U preserves inner products: ![]() . Consequently, it

also preserves lengths:

. Consequently, it

also preserves lengths: ![]() .

.

(b) An eigenvalue of U must have length 1.

(c) The columns of a unitary matrix form an orthonormal set.

Proof. (a)

![]()

Since U preserves inner products, it also preserves lengths of vectors, and the angles between them. For example,

![]()

(b) Suppose x is an eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue ![]() of U. Then

of U. Then ![]() , so

, so

![]()

But U preserves lengths, so ![]() , and hence

, and hence ![]() .

.

(c) Suppose

![$$U = \left[\matrix{ \uparrow & \uparrow & & \uparrow \cr c_1 & c_2 & \cdot & c_n \cr \downarrow & \downarrow & & \downarrow \cr}\right].$$](unitary-and-hermitian-matrices94.png)

Then ![]() means

means

![$$\left[\matrix{ \leftarrow & \overline{c_1}^T & \rightarrow \cr \leftarrow & \overline{c_2}^T & \rightarrow \cr & \vdots & \cr \leftarrow & \overline{c_n}^T & \rightarrow \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{ \uparrow & \uparrow & & \uparrow \cr c_1 & c_2 & \cdot & c_n \cr \downarrow & \downarrow & & \downarrow \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{ 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \cr 0 & 1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 1 & \cdots & 0 \cr \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \cr 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 1 \cr}\right].$$](unitary-and-hermitian-matrices96.png)

Here ![]() is the

complex conjugate of the

is the

complex conjugate of the ![]() column

column ![]() , transposed to make it a row vector. If

you look at the dot products of the rows of

, transposed to make it a row vector. If

you look at the dot products of the rows of ![]() and the columns of U, and note that the

result is I, you see that the equation above exactly expresses the

fact that the columns of U are orthonormal.

and the columns of U, and note that the

result is I, you see that the equation above exactly expresses the

fact that the columns of U are orthonormal.

For example, take the first row ![]() . Its product with the columns

. Its product with the columns

![]() ,

, ![]() , and so on give the first row of the

identity matrix, so

, and so on give the first row of the

identity matrix, so

![]()

This says that ![]() has length 1 and is

perpendicular to the other columns. Similar statements hold for

has length 1 and is

perpendicular to the other columns. Similar statements hold for ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() .

.![]()

Example. Find c and d so that the following matrix is unitary:

![$$\left[\matrix{ \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{7}} (1 + 2 i) & c \cr \noalign{\vskip2pt} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{7}} (1 - i) & d \cr}\right].$$ I want the columns to be orthogonal, so their complex dot product should be 0. First, I'll find a vector that is orthogonal to the first column. I may ignore the factor of $\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{7}}$; I need](unitary-and-hermitian-matrices108.png)

![$$\eqalign{ (a, b) \cdot (1 + 2 i, 1 - i) & = 0 \cr \left[\matrix{1 - 2 i & 1 + i \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{a \cr b \cr}\right] & = 0 \cr}$$](unitary-and-hermitian-matrices109.png)

This gives

![]()

I may take ![]() and

and ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

So I need to divide each of a and b by ![]() to get a unit vector. Thus,

to get a unit vector. Thus,

![]()

Proposition. (

Adjointness) let ![]() and let

and let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Proof.

![]()

Remark. If ![]() is any inner product on a vector

space V and

is any inner product on a vector

space V and ![]() is a linear

transformation, the adjoint

is a linear

transformation, the adjoint ![]() of T is the linear transformation which

satisfies

of T is the linear transformation which

satisfies

![]()

(This definition assumes that there is such a

transformation.) This explains why, in the special case of the

complex inner product, the matrix ![]() is called the

adjoint. It also explains the term

self-adjoint in the next definition.

is called the

adjoint. It also explains the term

self-adjoint in the next definition.

Corollary. (

Adjointness) let ![]() and let

and let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Proof. This follows from adjointness in the

complex case, because ![]() for a real matrix.

for a real matrix.![]()

Definition. An complex matrix A is Hermitian (or self-adjoint)

if ![]() .

.

Note that a Hermitian matrix is automatically square.

For real matrices, ![]() , and the

definition above is just the definition of a symmetric matrix.

, and the

definition above is just the definition of a symmetric matrix.

Example. Here are examples of Hermitian matrices:

![$$\left[\matrix{ -4 & 2 + 3i \cr 2 - 3i & 17 \cr}\right], \quad \left[\matrix{ 5 & 6i & 2 \cr -6i & 0.87 & 1 - 5i \cr 2 & 1 + 5i & 42 \cr}\right].$$](unitary-and-hermitian-matrices131.png)

It is no accident that the diagonal entries are real numbers --- see

the result that follows.![]()

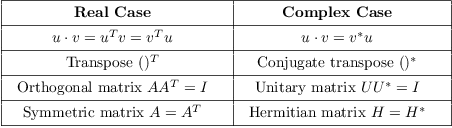

Here's a table of the correspondences between the real and complex cases:

Proposition. Let A be a Hermitian matrix.

(a) The diagonal elements of A are real numbers, and elements on opposite sides of the main diagonal are conjugates.

(b) The eigenvalues of a Hermitian matrix are real numbers.

(c) Eigenvectors of A corresponding to different eigenvalues are orthogonal.

Proof. (a) Since ![]() , I have

, I have ![]() . This shows

that elements on opposite sides of the main diagonal are conjugates.

. This shows

that elements on opposite sides of the main diagonal are conjugates.

Taking ![]() , I have

, I have

![]()

But a complex number is equal to its conjugate if and only if it's a

real number, so ![]() is real.

is real.

(b) Suppose A is Hermitian and ![]() is an eigenvalue of A with eigenvector v.

Then

is an eigenvalue of A with eigenvector v.

Then

![]()

Therefore, ![]() --- but a number that equals its complex conjugate

must be real.

--- but a number that equals its complex conjugate

must be real.

(c) Suppose ![]() is an eigenvalue of A

with eigenvector u and

is an eigenvalue of A

with eigenvector u and ![]() is an eigenvalue of A with eigenvector v.

Then

is an eigenvalue of A with eigenvector v.

Then

![]()

![]() implies

implies ![]() , so if the eigenvalues are

different, then

, so if the eigenvalues are

different, then ![]() .

.![]()

Example. Let

![]()

Show that the eigenvalues are real, and that eigenvectors for different eigenvalues are orthogonal.

The matrix is Hermitian. The characteristic polynomial is

![]()

The eigenvalues are real numbers: -4 and 2.

For -4, the eigenvector matrix is

![]()

![]() is an eigenvector.

is an eigenvector.

For 2, the eigenvector matrix is

![]()

![]() is an eigenvector.

is an eigenvector.

Note that

![]()

Thus, the eigenvectors are orthogonal.![]()

Since real symmetric matrices are Hermitian, the previous results apply to them as well. I'll restate the previous result for the case of a symmetric matrix.

Corollary. Let A be a symmetric matrix.

(a) The elements on opposite sides of the main diagonal are equal.

(b) The eigenvalues of a symmetric matrix are real numbers.

(c) Eigenvectors of A corresponding to different eigenvalues are

orthogonal.![]()

Example. Consider the symmetric matrix

![]()

The characteristic polynomial is ![]() .

.

Note that the eigenvalues are real numbers.

For ![]() , an eigenvector is

, an eigenvector is ![]() .

.

For ![]() , an eigenvector is

, an eigenvector is ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , the

eigenvectors are orthogonal.

, the

eigenvectors are orthogonal.![]()

Example. A ![]() real symmetric matrix A has

eigenvalues 1 and 3.

real symmetric matrix A has

eigenvalues 1 and 3.

![]() is an eigenvector corresponding to

the eigenvalue 1.

is an eigenvector corresponding to

the eigenvalue 1.

(a) Find an eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue 3.

Let ![]() be an eigenvector corresponding to

the eigenvalue 3.

be an eigenvector corresponding to

the eigenvalue 3.

Since eigenvectors for different eigenvalues of a symmetric matrix must be orthogonal, I have

![]()

So, for example, ![]() is a

solution.

is a

solution.![]()

(b) Find A.

From (a), a diagonalizing matrix and the corresponding diagonal matrix are

![]()

Now ![]() , so

, so

![]()

Note that the result is indeed symmetric.![]()

Example. Let ![]() , and consider the

, and consider the ![]() Hermitian matrix

Hermitian matrix

![]()

Compute the characteristic polynomial of A, and show directly that the eigenvalues must be real numbers.

![]()

The discriminant is

![]()

Since this is a sum of squares, it can't be negative. Hence, the

roots of the characteristic polynomial --- the eigenvalues --- must

be real numbers.![]()

Send comments about this page to: Bruce.Ikenaga@millersville.edu.

Copyright 2014 by Bruce Ikenaga