Induction is used to prove a sequence of

statements ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , .... There may be finitely many

statements, but often there are infinitely many.

, .... There may be finitely many

statements, but often there are infinitely many.

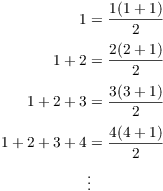

For example, consider the statement

![]()

This is actually an infinite set of statements, one for each integer

![]() :

:

You might think of proving this result by induction --- and in fact, I'll do so below.

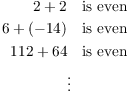

On the other hand, this statement is also an infinite set of statements:

![]()

However, there is one for each real number. You are unlikely to prove this by induction.

The fact that a statement involves integers does not mean induction is appropriate. For example, consider the statement

"The sum of two even numbers is even."

It's true that this is a statement about an infinite set of pairs of integers.

However, the problem with using induction here is that there isn't an obvious way to arrange the statements in a sequence.

Likewise, consider the statement

"If n is an integer, then ![]() is odd."

is odd."

While it's conceivable that you could give an induction proof, it

would be overkill: ![]() expresses

expresses ![]() as 2 times something plus 1, so it must be odd.

as 2 times something plus 1, so it must be odd.

How does induction work? Suppose you have a sequence of statements

![]() ,

, ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() , ..., one for each

positive integer. (There's no harm in starting your numbering with 0

if it's convenient.) In the simplest case, to give a proof by

induction:

, ..., one for each

positive integer. (There's no harm in starting your numbering with 0

if it's convenient.) In the simplest case, to give a proof by

induction:

1. Prove ![]() .

.

2. Let ![]() , and assume

, and assume ![]() is

true.

is

true.

3. Using the assumption that ![]() is true, prove that

is true, prove that

![]() must be true.

must be true.

If you can complete these steps, you can conclude that ![]() is true for all

is true for all ![]() , by induction.

, by induction.

The assumption that ![]() is true is often called the induction hypothesis, or the

inductive assumption.

is true is often called the induction hypothesis, or the

inductive assumption.

Why does it work? Induction follows from a fundamental fact about the positive integers called the Well-Ordering Axiom.

Well-Ordering Axiom. Every nonempty subset of the positive integers has a smallest element.

The Well-Ordering Axiom is an axiom for the positive integers, so there's no question of proving it.

Example. Verify the Well-Ordering Axiom for the following subsets of positive integers:

(a) The positive even integers: ![]() .

.

(b) The subset of the positive integers which consists of positive integers whose decimal representations begin and end with "1". For example, 101, 128391, and 1651 are elements of this set.

(a) The smallest element of this set is 2.![]()

(b) The smallest element of this set is 1.![]()

Theorem. (Principle of

Mathematical Induction) Let ![]() ,

, ![]() , ... be a set of statements indexed by the positive integers.

Suppose that:

, ... be a set of statements indexed by the positive integers.

Suppose that:

(a) ![]() is true.

is true.

(b) For every ![]() , if

, if ![]() is true, then

is true, then ![]() is true.

is true.

Then ![]() is true for all

is true for all ![]() .

.

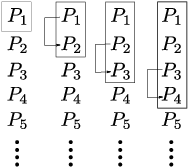

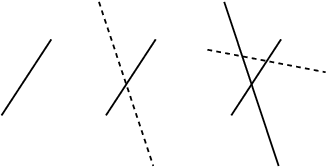

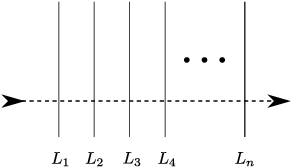

The intuitive idea is illustrated below:

Assumption (a) says that ![]() is true. Assumption (b) says that

if a statement is true, the next statement below it is true. I've

represented this with a "C-shaped" arrow connector from the

known true statement to the next one. As you move the connector down,

you find that

is true. Assumption (b) says that

if a statement is true, the next statement below it is true. I've

represented this with a "C-shaped" arrow connector from the

known true statement to the next one. As you move the connector down,

you find that ![]() being true makes

being true makes ![]() true,

true, ![]() being true makes

being true makes ![]() true, and so on. Thus, all the statements

are true.

true, and so on. Thus, all the statements

are true.

Proof. I'll prove the result by contradiction.

Assume that ![]() is true, and for every

is true, and for every ![]() , if

, if ![]() is true, then

is true, then ![]() is true. Suppose that it

isn't true that

is true. Suppose that it

isn't true that ![]() is true for all

is true for all ![]() .

.

Consider the set of integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() is false. Since

is false. Since ![]() is not true for all

is not true for all ![]() , there must be some n for which

, there must be some n for which ![]() is false. Hence, the set of integers

is false. Hence, the set of integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() is false is nonempty.

is false is nonempty.

Since this is a nonempty subset of the positive integers, by

Well-Ordering it contains a smallest element MIN. Thus, ![]() is false, and

is false, and ![]() is not false (i.e.

is not false (i.e. ![]() is true) for all

is true) for all ![]() .

.

Now MIN can't be 1, because ![]() is true by assumption. Thus,

is true by assumption. Thus, ![]() . So

. So ![]() is a positive integer, and

is a positive integer, and

![]() must be true.

must be true.

But now my second assumption --- if a statement in the sequence is

true, the following statement is true --- shows that ![]() must be true. This contradicts

the fact that

must be true. This contradicts

the fact that ![]() is false.

is false.

This contradiction proves that ![]() is true for all

is true for all ![]() .

.![]()

Remark. You can also do the induction step by

assuming the result for n, and proving it for ![]() , and I will often do this. Usually, there is no

difference in the difficulty, so you should use whichever approach

you find comfortable.

, and I will often do this. Usually, there is no

difference in the difficulty, so you should use whichever approach

you find comfortable.

Also, some inductions begin with a statement numbered "0" --- or "42". The numbering doesn't matter.

Example. Prove that

![]()

The formula is true for ![]() , since the left side is 1 and the

right side is

, since the left side is 1 and the

right side is

![]()

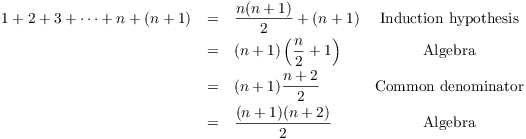

Suppose the formula holds for n. This means that

![]()

I want to prove that the formula holds for ![]() .

.

Suggestion: You might want to write the

formula for ![]() out on scratch paper so you know what

you're trying to prove. You get it by replacing "n" with

"

out on scratch paper so you know what

you're trying to prove. You get it by replacing "n" with

"![]() " in the formula for n:

" in the formula for n:

![]()

Don't start with this equation! --- that would be assuming what you want to prove. Instead, start with the left side and work until you get the right side.

This proves the formula for ![]() . Hence, the result is true for

all

. Hence, the result is true for

all ![]() , by induction.

, by induction.![]()

Notice that when I wrote out the left side of the formula for ![]() I put in both the final term "

I put in both the final term "![]() " and the term before it, which is

"n". In that way, I could see the expression "

" and the term before it, which is

"n". In that way, I could see the expression "![]() " which is the left side of my

induction assumption --- so I knew to begin by substituting. This

trick is often useful in the induction step.

" which is the left side of my

induction assumption --- so I knew to begin by substituting. This

trick is often useful in the induction step.

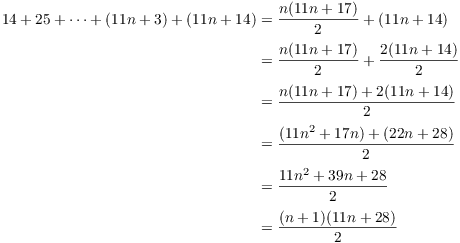

Example. Prove that for ![]()

![]()

The formula is true for ![]() , since the left side is 14 and

the right side is

, since the left side is 14 and

the right side is

![]()

Suppose the formula holds for n. This means that

![]()

I need to prove the formula for ![]() .

.

On scratch paper, I write out the formula for ![]() ; it is

; it is

![]()

Remember not to start with this equation --- start with the

left side! Notice that on the left side I wrote out the final term

(![]() ), then wrote out the previous

term (

), then wrote out the previous

term (![]() ). This helps me recognize the left side of the

induction assumption.)

). This helps me recognize the left side of the

induction assumption.)

Continuing with our proof, here's the proof of the formula for ![]() . I won't write out justifications for steps this

time, as most of it is basic algebra.

. I won't write out justifications for steps this

time, as most of it is basic algebra.

This proves the result for ![]() , so the result is true for all

, so the result is true for all

![]() by induction.

by induction.![]()

Are you wondering how I made the final step?

![]()

The idea is that I knew from my scratch work that the final answer

had to be ![]() . So I wrote it down,

then checked that it worked by multiplying out

. So I wrote it down,

then checked that it worked by multiplying out ![]() to see if I got

to see if I got ![]() . Nobody

"knows" how you got the final step --- the question is

whether it's true!

. Nobody

"knows" how you got the final step --- the question is

whether it's true!

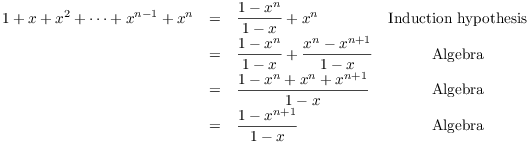

Example. Let ![]() ,

, ![]() . Prove that

. Prove that

![]()

You're allowed to "begin" an induction with ![]() --- or any other integer --- if it's convenient to do

so.

--- or any other integer --- if it's convenient to do

so.

For ![]() ,

,

![]()

The result is true for ![]() .

.

(For variety, I'll do this induction step by assuming the result for

![]() and proving it for n. The amount of work is about the

same as assuming it for n and proving it for

and proving it for n. The amount of work is about the

same as assuming it for n and proving it for ![]() .)

.)

Assume that ![]() , and that the result holds for

, and that the result holds for ![]() :

:

![]()

I want to show that the result holds for n.

This proves the result for n, so the result is true for all ![]() , by induction.

, by induction.![]()

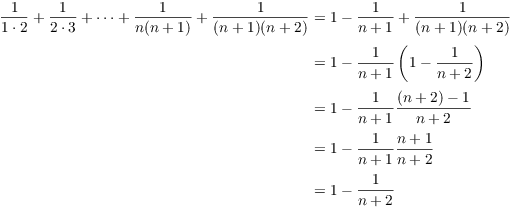

Example. Let ![]() ,

, ![]() . Prove that

. Prove that

![]()

You may have seen this idea when you learned about infinite series; it's called telescoping:

![]()

The "argument" is that the terms cancel in pairs, leaving

![]() .

.

Arguments where you say "and so on" are often justified rigorously by induction. That's what I'll do here.

For ![]() ,

,

![]()

The result is true for ![]() .

.

Assume that the result is true for n:

![]()

I want to show that the result holds for ![]() .

.

This proves the result for ![]() , so the result is true for all

, so the result is true for all

![]() , by induction.

, by induction.![]()

In some situations, it's convenient to give an induction proof in the following form:

1. Prove ![]() .

.

2. Let ![]() , and assume

, and assume ![]() is true for

all

is true for

all ![]() .

.

3. Using the assumption that ![]() is true for all

is true for all ![]() , prove that

, prove that ![]() must be true.

must be true.

In other words, you can take as your induction hypothesis the truth

of all the statements prior to the ![]() statement, which you are trying to prove. This is

sometimes called generalized induction or strong induction.

statement, which you are trying to prove. This is

sometimes called generalized induction or strong induction.

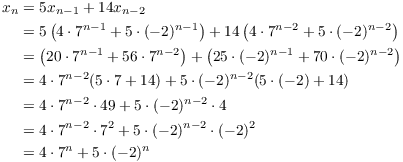

Example. Define a sequence of integers by

![]()

Prove that

![]()

To get the induction started, I have to verify the formula ![]() for both

for both ![]() and

and ![]() . The reason is that the recursion

formula doesn't kick in till

. The reason is that the recursion

formula doesn't kick in till ![]() .

.

For ![]() , the formula gives

, the formula gives

![]()

For ![]() , the formula gives

, the formula gives

![]()

The formula holds for ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Now assume that ![]() and the formula holds for all

and the formula holds for all ![]() , i.e. for all numbers less than n. In particular,

since

, i.e. for all numbers less than n. In particular,

since ![]() and

and ![]() are less than n, I have

are less than n, I have

![]()

The fact that I need both of these formulas to do the induction step

is why I'm using a generalized or strong induction. If I did a

standard induction where I just assumed the result for ![]() , I would not have it for

, I would not have it for ![]() .

.

I have to show that the formula holds for n. I start with the

recursion formula that defines ![]() , substitute the

results for

, substitute the

results for ![]() and

and ![]() , and do some algebra:

, and do some algebra:

This proves the result for n, so the result holds for all ![]() by induction.

by induction.![]()

Here are some remarks about the algebra I did. My target expression

![]() has a power of 7 and a power of

-2. So I began by grouping terms into powers of 7 and powers of -2.

has a power of 7 and a power of

-2. So I began by grouping terms into powers of 7 and powers of -2.

Next, to try to make what I had look like what I wanted, I factor out

![]() and

and ![]() . Then

simplifying what was left produced the powers (

. Then

simplifying what was left produced the powers (![]() and

and ![]() ) that I needed to finish. Perhaps it looks like

magic, but as we've seen in other proofs, if your steps are correct,

it has to work --- you know what the final expression should be.

) that I needed to finish. Perhaps it looks like

magic, but as we've seen in other proofs, if your steps are correct,

it has to work --- you know what the final expression should be.

In the examples that follow, I use induction to prove inequalities and a divisibility result. The general setup for the inductions remains the same --- it's just the specific work that differs.

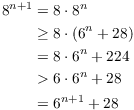

Example. Prove that

![]()

For ![]() ,

,

![]()

The result holds for ![]() .

.

Assume that the result holds for n:

![]()

I'll prove it for ![]() . To get the proof started, I make a

"

. To get the proof started, I make a

"![]() " term appear using algebra, so I can use the

induction assumption.

" term appear using algebra, so I can use the

induction assumption.

(In the inequality which gave the second-to-the-last line, I used the

facts that ![]() and

and ![]() to replace the existing terms

so I could match the target.)

to replace the existing terms

so I could match the target.)

This proves the result for ![]() , so the result is true for all

, so the result is true for all

![]() by induction.

by induction.![]()

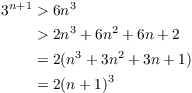

Example. Prove that for ![]() ,

,

![]()

In this case, the basis step is ![]() , because the result is to be

proved for

, because the result is to be

proved for ![]() . (Try some numbers and you'll find the

. (Try some numbers and you'll find the

![]() can be bigger than

can be bigger than ![]() for some numbers

smaller than 6 .)

for some numbers

smaller than 6 .)

For ![]() ,

,

![]()

The result is true for ![]() .

.

Assume that the result holds for n:

![]()

I have to prove the result for ![]() .

.

Thus, I have

![]()

On scratch paper, I see that my target inequality is

![]()

So my strategy will be to break up the ![]() that I have so far

into 4 pieces, each of which will be greater than or equal to one of

the 4 pieces of

that I have so far

into 4 pieces, each of which will be greater than or equal to one of

the 4 pieces of ![]() . I will do this in steps.

. I will do this in steps.

Since ![]() and

and ![]() , I have

, I have

![]()

Again, since ![]() , multiplying both sides by

, multiplying both sides by ![]() , I get

, I get

![]()

Since ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() . So taking the last inequality and adding another

term, I have

. So taking the last inequality and adding another

term, I have

![]()

Finally, ![]() gives

gives

![]()

Adding the inequalities (1), (2), (3), and (4), I have

![]()

Combine this with the inequality I proved earlier:

This proves the result for ![]() , so the result is true for all

, so the result is true for all

![]() by induction.

by induction.![]()

There are other ways to prove the key inequality ![]() . For example, you could use

calculus: After some algebra, you get the inequality

. For example, you could use

calculus: After some algebra, you get the inequality ![]() . Take

. Take ![]() . Note that

. Note that ![]() , and show that

, and show that ![]() for

for ![]() , so the function increases.

, so the function increases.

This proof is a little involved, so for starters try to understand why each step is correct before trying to grasp the whole. Don't feel bad if you think that you wouldn't have figured this out by yourself! There are math problems that stump even the best mathematicians. The more experience you get, the more you will be able to do by yourself.

For the next example, remember that if m and n are integers, m

divides n (in symbols, ![]() ) if

) if ![]() for some integer

n.

for some integer

n.

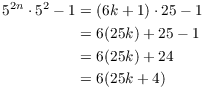

Example. Prove that for ![]() ,

,

![]()

You can do this proof directly, without induction. But I'll give an induction proof by way of example.

For ![]() , I have

, I have

![]()

Since ![]() , the result holds for

, the result holds for ![]() .

.

Assume that the result holds for n:

![]()

I can write this as ![]() for some integer k, or

for some integer k, or

![]()

I must prove the result for ![]() . As usual, the first thing I'll

do is to work on the given expression to get (part of) the induction

assumption to appear.

. As usual, the first thing I'll

do is to work on the given expression to get (part of) the induction

assumption to appear.

![]()

I have the "![]() " which is part of the induction

assumption. Now

" which is part of the induction

assumption. Now ![]() means

means ![]() for some integer k, or

for some integer k, or

![]()

Substituting this into the expression above, I get

All together,

![]()

Therefore, ![]() . This proves the result for

. This proves the result for

![]() , so the result holds for

, so the result holds for ![]() by induction.

by induction.![]()

Here's a sketch of a direct proof: Write ![]() . Then use the formula

. Then use the formula

![]()

Lines and regions in the plane. This is an extended example which illustrates how you might "guess" a formula, then confirm it using induction.

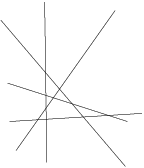

Suppose we draw lines in the plane, one after another:

Each line that we draw should satisfy the following conditions:

1. It should not be parallel to any of the previous lines.

2. It should intersect all of the previous lines.

3. It should not pass through the intersection point of any two of the previous lines.

The lines in the picture above satisfy these conditions.

Question: Into how many regions do the lines divide the plane?

Before we even consider this question, we should be careful that we can actually do what we require. In particular, how do we know we can satisfy conditions 2 and 3?

Try it yourself (maybe with a drawing program on a computer). It starts to become a little tricky to get the next line to cross all of the previous lines. Imagine that you had 100 lines and you were trying to draw one more!

I'll prove this is possible by induction.

Proposition. Suppose there are n lines in the plane, each of which intersects all the others, and such that no three lines intersect. Then there is a line which intersects all n lines, and does not go through any of their intersections.

Proof. From geometry, two lines are parallel if and only if they have the same slope. So if two lines have different slopes, they aren't parallel, and they must intersect. We'll use this to give an induction proof.

We can get started and draw the first line wherever we want.

Then suppose we've draw lines ![]() ,

, ![]() , and so on, all the

way up to

, and so on, all the

way up to ![]() . We want to draw the

. We want to draw the ![]() line so

that it intersects the n previous lines.

line so

that it intersects the n previous lines.

Suppose the slope of ![]() is

is ![]() , the slope of

, the slope of ![]() is

is ![]() , and so on. We have n slopes:

, and so on. We have n slopes:

![]()

These are n different numbers (where a "number" could include the designation "undefined" if one of the lines is vertical). The numbers are different because these n lines intersect, and these numbers are their slopes.

Pick a number ![]() which is different from all of these m's.

To make the arguments that follow easier, I'll also assume

which is different from all of these m's.

To make the arguments that follow easier, I'll also assume ![]() is not "undefined". I can pick such a

number

is not "undefined". I can pick such a

number ![]() because there are infinitely many real

numbers, so there are real numbers different from the previous m's

and "undefined".

because there are infinitely many real

numbers, so there are real numbers different from the previous m's

and "undefined".

Consider a line ![]() with slope

with slope ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is different from all the other

m's, the line

is different from all the other

m's, the line ![]() must intersect the n previous lines.

must intersect the n previous lines.

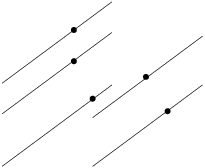

How can we ensure that this new line does not go through the

intersections of any of the previous lines? The n previous lines

intersect in a finite number of points. Consider the lines with slope

![]() which go through these intersection points.

which go through these intersection points.

In the picture above, the dots represent the intersection point of

the previous lines, and the lines I've drawn show the lines with

slope ![]() which pass through them.

which pass through them.

Each of those lines has a y-intercept, so there are finitely many such y-intercepts.

Let's say the y-intercepts are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and so on. Because there are only finitely many b's, I can choose a

number b different from all of them.

, and so on. Because there are only finitely many b's, I can choose a

number b different from all of them.

Consider the line ![]() . It has slope

. It has slope ![]() , so it intersects all the previous lines. Its

y-intercept is different from the y-intercepts of all the

intersection point lines, so it does not pass through any of the

intersection points.

, so it intersects all the previous lines. Its

y-intercept is different from the y-intercepts of all the

intersection point lines, so it does not pass through any of the

intersection points.

This proves the result for n lines, so it's true for any number of

lines, by induction.![]()

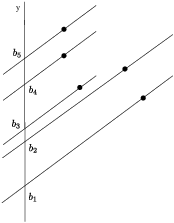

At this point, we know our question makes sense, so we can think about answering it. Let's see if we can see a pattern.

We go from 2 regions to 4 regions, and ![]() . We go from 4

regions to 7 regions, and

. We go from 4

regions to 7 regions, and ![]() . If you draw a picture,

you'll find that with 4 lines there are 11 regions, and

. If you draw a picture,

you'll find that with 4 lines there are 11 regions, and ![]() . Let's set up some notation. Let

. Let's set up some notation. Let ![]() be the number of regions made by n lines. It appears that

be the number of regions made by n lines. It appears that

![]()

The formula seems to work for ![]() .

.

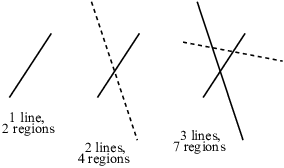

Let's see if we can verify this with a picture. Suppose I have n

lines. When I draw the ![]() line, it must cross each of

the previous n lines. Schematically:

line, it must cross each of

the previous n lines. Schematically:

As the new line crosses ![]() , it splits the region on the left

of

, it splits the region on the left

of ![]() , and one new region is added. As the new line

crosses

, and one new region is added. As the new line

crosses ![]() , it splits the region between

, it splits the region between ![]() and

and ![]() , and one new region is added. And so on. All

together,

, and one new region is added. And so on. All

together, ![]() new regions are added. That is,

new regions are added. That is, ![]() regions are added to

regions are added to ![]() to get

to get ![]() .

.

This recursion isn't bad, but it would be nice to have a

"closed-form" expression which gives ![]() in terms of n. We'll show how to go from the recursion to such an

expression in the next theorem.

in terms of n. We'll show how to go from the recursion to such an

expression in the next theorem.

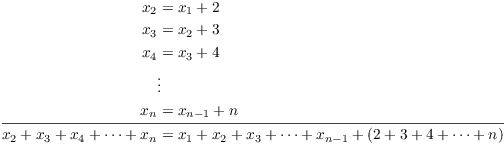

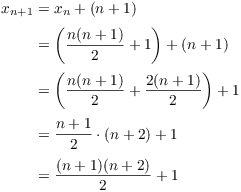

Theorem. Suppose ![]() , and a sequence

is defined recursively by

, and a sequence

is defined recursively by ![]() , and

, and

![]()

Then for ![]() ,

,

![]()

Proof. Method 1. This method doesn't use induction, but I'll point out afterward some details which it omits.

Write out the recursion ![]() for

for ![]() , then add the equations:

, then add the equations:

I subtract ![]() from both sides:

from both sides:

![]()

Now

![]()

Also, ![]() . Plugging these into the equation for

. Plugging these into the equation for ![]() , I get

, I get

![]()

Method 2. For ![]() , the formula gives

, the formula gives

![]()

The result holds for ![]() .

.

Assume that the result is true for n:

![]()

I will prove it for ![]() :

:

This proves the result for ![]() , so the result is true for all

, so the result is true for all

![]() by induction.

by induction.![]()

The first method may seem pretty appealing --- you may have seen similar techniques used in computing values of infinite series ("telescoping"). Depending on what you're willing to assume, this may be adequate as a proof. Let's note a couple of things.

First, what does "![]() " mean?

Maybe it's obvious to you: It means "add up the numbers

" mean?

Maybe it's obvious to you: It means "add up the numbers ![]() ,

, ![]() , and so on up to

, and so on up to ![]() . However, addition is a binary

operation: It tells you how to add 2 numbers at a time, not 100

numbers or

. However, addition is a binary

operation: It tells you how to add 2 numbers at a time, not 100

numbers or ![]() numbers. Adding more than two numbers at a

time actually requires a definition.

numbers. Adding more than two numbers at a

time actually requires a definition.

Well, you might say: Just add the numbers two at a time. And in fact,

you can define a sum of more than 2 numbers recursively in this way:

If you already know how to add n numbers, then to add ![]() numbers, you can make the following definition:

numbers, you can make the following definition:

![]()

The right side is a sum of two numbers, so this works.

But a second issue arises, and that is that the definition above picks a particular way of grouping the numbers when you add. Now the associative law for addition tells you that you get the same thing when you group 3 numbers for addition in two different ways:

![]()

However, when I write "![]() "

I'm implying that if I add any number of numbers, I get the

same result regardless of how I group the additions. For example,

"

I'm implying that if I add any number of numbers, I get the

same result regardless of how I group the additions. For example,

![]()

Try deriving the last line using associativity for just three numbers. We're saying that the same thing works for any grouping, and any number of numbers. And it's true! How do you prove it? You use induction! I won't give the proof here, but you might try it yourself as a challenge.

In other math courses, you didn't worry about these issues, and things work the way you'd expect. But as you've already noticed, proving things is a lot harder than simply know or believing that they're true.

Copyright 2019 by Bruce Ikenaga