We've already seen examples of proofs of inequalities as examples of various proof techniques. In this section, we'll discuss assorted inequalities and the heuristics involved in proving them. The subject of inequalities is vast, so our discussion will barely scratch the surface.

Here are a couple of basic rules which I'll use constantly.

1. You can add a number to both (or all sides) of an inequality.

2. You can multiply an inequality by a nonzero number --- but if the number you multiply by is negative, the inequality is reversed.

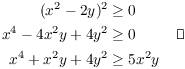

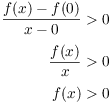

Example. Prove that ![]() .

.

The ![]() looks like it came from

looks like it came from ![]() . I know that even powers are always

. I know that even powers are always ![]() . I'll start with

. I'll start with ![]() and

see if I can get the desired inequality:

and

see if I can get the desired inequality:

Example. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . And if

. And if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() . Is it true that if

. Is it true that if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() ?

?

The statement is false. For example, ![]() and

and ![]() , but

, but ![]() .

.

This result shows that you have to be careful in the rules you use to

work with inequalities. Some "rules" which look obvious

aren't correct.![]()

In fact, the false result in the example can be "fixed" by placing additional assumptions on a, b, c, and d. To prove the correct result, I'll have to use very basic facts about inequalities involving real numbers.

Here are some axioms for the standard order relation on ![]() . Everything is defined in terms of a subset

. Everything is defined in terms of a subset ![]() , the positive real numbers.

, the positive real numbers.

1. For every real number x, either ![]() ,

, ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

2. The sum of positive real numbers is a positive real number.

3. The product of positive real numbers is a positive real number.

The order relation ![]() is defined in terms of

is defined in terms of ![]() . Think about a statement like "

. Think about a statement like "![]() ". Another way to say this is: You add a

positive number (namely 4) to 3 to get 7.

". Another way to say this is: You add a

positive number (namely 4) to 3 to get 7.

Definition. If ![]() ,

, ![]() means that

means that ![]() , where

, where ![]() .

.

As usual, ![]() means

means ![]() ,

, ![]() means

means ![]() or

or ![]() , and

, and ![]() means

means ![]() .

.

Here is a "fixed" version of the incorrect rule in the last example. The proof illustrates a standard approach in inequality proofs involving the basic axioms: Convert inequality statements to equations and work with the equations.

Lemma. Suppose a, b, c, and d are positive

real numbers, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() .

.

Proof. Suppose ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Write

. Write

![]()

Then

![]()

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are positive, because each is

the product of positive numbers. Hence,

are positive, because each is

the product of positive numbers. Hence, ![]() is

positive. The equation above therefore shows that

is

positive. The equation above therefore shows that ![]() .

.![]()

Lemma. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

Proof. Since ![]() , I know that

, I know that ![]() , where

, where ![]() . Hence,

. Hence,

![]()

But since ![]() , this means that

, this means that ![]() .

.![]()

Plainly, the same proof works if addition is replaced with subtraction.

You can often prove an inequality by transforming or substituting in a known inequality. Unfortunately, there are infinitely many inequalities you can start with! You have to rely on your knowledge of mathematics, as well as common sense: If you're trying to prove an inequality in calculus, for example, it's natural to think of all the "calculus inequalities" you know.

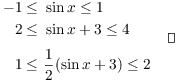

Example. ( Using a known trig

inequality) Prove that for all ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

The "![]() " form of the

inequality and the presence of the

" form of the

inequality and the presence of the ![]() in the middle

remind me of

in the middle

remind me of ![]() , so I'll start with that and

do some algebra:

, so I'll start with that and

do some algebra:

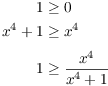

Example. ( Using an integral

inequality) From calculus, you know that if f and g are

integrable functions and ![]() on

on ![]() , then

, then

![]()

Use this inequality to prove that

![]()

I have

Applying the integral inequality, I get

![]()

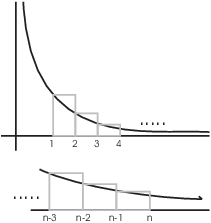

You can often "see" that an inequality is true by drawing a

picture. For example, draw the graph of ![]() for

for ![]() , where n is an integer greater than 1.

, where n is an integer greater than 1.

Divide the interval ![]() up into n equal pieces, and build

a rectangle on each piece, using the left-hand endpoints of each

subinterval to get the heights. As you can see from the picture, the

rectangles all lie above the curve, so the sum of the rectangle areas

will be greater than the area under the curve.

up into n equal pieces, and build

a rectangle on each piece, using the left-hand endpoints of each

subinterval to get the heights. As you can see from the picture, the

rectangles all lie above the curve, so the sum of the rectangle areas

will be greater than the area under the curve.

The first rectangle has base 1 and height 1, so its area is 1. The

second rectangle has base 1 and height ![]() , so its area

is

, so its area

is ![]() . Continuing in this way, the last

rectangle has base 1 and height

. Continuing in this way, the last

rectangle has base 1 and height ![]() , so its

area is

, so its

area is ![]() .

.

The area under the curve is ![]() .

.

Therefore,

![]()

This inequality is correct (and by the way, you can use it to see

that the harmonic series ![]() diverges). But the argument I gave is not a

completely rigorous proof.

diverges). But the argument I gave is not a

completely rigorous proof.

I'm assuming that the picture accurately represents the situation. To

prove that this is the case takes some work. For example,

I'd need to prove that each rectangle really does lie above

the curve. This would involve noting that ![]() shows that the graph is decreasing, then

using this to prove that the left-hand endpoints give the maximum

value of

shows that the graph is decreasing, then

using this to prove that the left-hand endpoints give the maximum

value of ![]() on each subinterval.

on each subinterval.

Pictures can help you see or remember that something is true, and sometimes a picture or a heuristic argument is useful in teaching --- to avoid obscuring the idea with technicalities. But you should never confuse a picture with a rigorous proof!

Example. ( Using the Mean

Value Theorem) Prove that for all ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

Let ![]() . Take

. Take ![]() and apply the Mean Value Theorem to f on the interval

and apply the Mean Value Theorem to f on the interval

![]() . The Mean Value Theorem implies that there is a

number c such that

. The Mean Value Theorem implies that there is a

number c such that ![]() and

and

![]()

Now ![]() , and

, and ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

Therefore, ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.![]()

In some cases, you can use a known inequality to prove other inequalities. Here are some well-known inequalities.

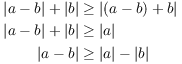

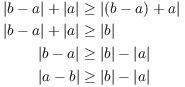

The Triangle Inequality. Let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

The name "Triangle Inequality" comes from the corresponding

inequality when x and y are vectors. In that case, it says that the

sum of the lengths of two sides of a triangle (![]() ) is greater than or equal to the length of the third

side (

) is greater than or equal to the length of the third

side (![]() ).

).

The Arithmetic-Geometric Mean Inequality. Let

![]() , and suppose that

, and suppose that ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

If x and y are two nonnegative numbers, their

arithmetic mean ("average") is ![]() and their geometric mean is

and their geometric mean is

![]() --- hence the name of this inequality.

--- hence the name of this inequality.

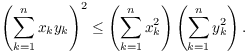

The Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality. If ![]() , then

, then

You may have seen this inequality in a vector calculus course or a linear algebra course. Let

![]()

Then the vector form of the inequality is

![]()

(The product on the left side is the dot product of the two vectors.)

Example. ( Using the Triangle Inequality) Prove that if a and b are real numbers, then

![]()

Apply the Triangle Inequality with ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

Apply the Triangle Inequality with ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

The last step follows from the fact that ![]() .

.

Now

![]()

I've show that in both of these two cases, ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.![]()

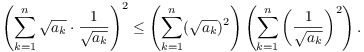

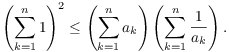

Example. ( Using the

Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality) Prove that if ![]() , then

, then

![]()

Apply the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality with

![]()

I get

This simplifies to

But ![]() , so

, so

![]()

As in this example, the trick to applying known inequalities is

figuring out what substitutions to make.![]()

Copyright 2018 by Bruce Ikenaga