A partial order on a set is, roughly speaking,

a relation that behaves like the relation ![]() on

on ![]() .

.

Definition. Let X be a set, and let ![]() be a relation on X.

be a relation on X. ![]() is a

partial order if:

is a

partial order if:

(a) (Reflexive) For all ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

(b) (Antisymmetric) For all ![]() , if

, if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

(c) (Transitive) For all ![]() , if

, if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

Example. For each relation, check each axiom for a partial order. If the axiom holds, prove it. If the axiom does not hold, give a specific counterexample.

(a) The relation ![]() on

on ![]() .

.

(b) The relation ![]() on

on ![]() .

.

(a) For all ![]() ,

, ![]() : Reflexivity

holds.

: Reflexivity

holds.

For all ![]() , if

, if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() : Antisymmetry holds.

: Antisymmetry holds.

For all ![]() , if

, if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() : Transitivity holds.

: Transitivity holds.

Thus, ![]() is a partial order.

is a partial order.![]()

(b) For no x is it true that ![]() , so reflexivity fails.

, so reflexivity fails.

Antisymmetry would say: If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() . However, for no

. However, for no ![]() is it true that

is it true that ![]() and

and ![]() . Therefore, the first part of the conditional is

false, and the conditional is true. Thus, antisymmetry is

vacuously true.

. Therefore, the first part of the conditional is

false, and the conditional is true. Thus, antisymmetry is

vacuously true.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() . Therefore, transitivity holds.

. Therefore, transitivity holds.

Hence, ![]() is not a partial order.

is not a partial order.![]()

Example. Let X be a set and let ![]() be the power set of X --- i.e. the set of all subsets

of X. Show that the relation of set inclusion

is a partial order on

be the power set of X --- i.e. the set of all subsets

of X. Show that the relation of set inclusion

is a partial order on ![]() .

.

Subsets A and B of X are related under set inclusion if ![]() .

.

If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . The relation

is reflexive.

. The relation

is reflexive.

Suppose ![]() . If

. If ![]() and

and ![]() , then by definition of set

equality,

, then by definition of set

equality, ![]() . The relation is symmetric.

. The relation is symmetric.

Finally, suppose ![]() . If

. If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() . (You can write out the easy proof using elements.)

The relation is transitive.

. (You can write out the easy proof using elements.)

The relation is transitive.

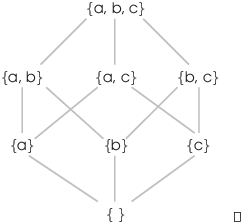

Here's a particular example. Let ![]() . This is

a picture of the set inclusion relation on

. This is

a picture of the set inclusion relation on ![]() :

:

Definition. Let ![]() be a partially ordered set. The

lexicographic order (or dictionary order)

on

be a partially ordered set. The

lexicographic order (or dictionary order)

on ![]() is defined as follows:

is defined as follows: ![]() means that

means that

(a) ![]() , or

, or

(b) ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Note that ![]() implies

implies ![]() .

.

You can extend the definition to two different partially ordered sets

X and Y, or a sequence ![]() ,

, ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() of partially ordered sets in the same way. The name

dictionary order comes from the fact that it describes the

way words are ordered alphabetically in a dictionary. For instance,

"aardvark" comes before "banana" because

"a" comes before "b". If the first letters are

the same, as with "mystery" and "meat", then you

look at the second letters: "e" comes before "y",

so "meat" comes before "mystery".

of partially ordered sets in the same way. The name

dictionary order comes from the fact that it describes the

way words are ordered alphabetically in a dictionary. For instance,

"aardvark" comes before "banana" because

"a" comes before "b". If the first letters are

the same, as with "mystery" and "meat", then you

look at the second letters: "e" comes before "y",

so "meat" comes before "mystery".

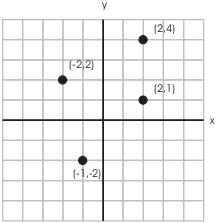

In the picture above, ![]() , because

, because ![]() . And

. And ![]() because the

x-coordinates are equal and

because the

x-coordinates are equal and ![]() .

.

Proposition. The lexicographic order on ![]() is a partial order.

is a partial order.

Proof. First, ![]() , since

, since

![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() is reflexive.

is reflexive.

Next, suppose ![]() and

and ![]() . Now

. Now ![]() means that either

means that either ![]() or

or ![]() . The first case

. The first case ![]() is impossible, since this would contradict

is impossible, since this would contradict ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() implies

implies

![]() and

and ![]() implies

implies ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() .

.

![]() is antisymmetric.

is antisymmetric.

Finally, suppose ![]() and

and ![]() . To keep things organized, I'll

consider the four cases.

. To keep things organized, I'll

consider the four cases.

(a) If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

(b) If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

(c) If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

(d) If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() and

and ![]() . This implies

. This implies ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() is transitive, and this completes the proof

that

is transitive, and this completes the proof

that ![]() is a partial order.

is a partial order.![]()

A common mistake in working with partial orders --- and in real life --- consists of assuming that if you have two things, then one must be bigger than the other. When this is true about two things, the things are said to be comparable. However, in an arbitrary partially ordered set, some pairs of elements are comparable and some are not.

Definition. Let ![]() be a relation on a set X. x and y in X are comparable if either

be a relation on a set X. x and y in X are comparable if either ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

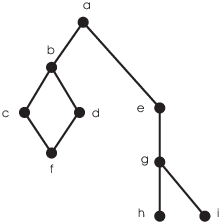

Here's a pictorial example to illustrate the idea. You can sometimes describe an order relation by drawing a graph like the one below:

This picture shows a relation ![]() on the set

on the set

![]()

Two elements are comparable if they're joining by a sequence of edges

that goes upward "without reversing direction". (Think of

"bigger" elements being above and "smaller"

elements being below.) It's also understood that every element

satisfies ![]() .

.

For example, ![]() , since there's an upward segment

connecting f to c. And

, since there's an upward segment

connecting f to c. And ![]() , since there's an upward path

of segments

, since there's an upward path

of segments ![]() connecting f to a.

connecting f to a.

On the other hand, there are elements which are not comparable. For

example, d and e are not comparable, because there is no upward path

of segments connecting one to the other. Likewise, ![]() and

and ![]() , but h and i are not

comparable.

, but h and i are not

comparable.

Notice that a is comparable to every element of the set, and that

![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.

Definition. Let X be a partially ordered set.

(a) An element ![]() which is comparable to every other

element of X and satisfies

which is comparable to every other

element of X and satisfies ![]() for all

for all ![]() is the largest element of the

set.

is the largest element of the

set.

(b) An element ![]() which is comparable to every other

element of X and satisfies

which is comparable to every other

element of X and satisfies ![]() for all

for all ![]() is the smallest element of the

set.

is the smallest element of the

set.

In some cases, we only care that an element be "bigger than" or "smaller than" elements to which it is comparable.

Definition. Let X be a partially ordered set.

If an element x satisfies ![]() for all y to which it is

comparable, then x is a maximal element.

Likewise, if an element x satisfies

for all y to which it is

comparable, then x is a maximal element.

Likewise, if an element x satisfies ![]() for all y to which

it is comparable, then x is a minimal element.

for all y to which

it is comparable, then x is a minimal element.

Note that a largest or smallest element, if it exists, is unique. On the other hand, there may be many maximal or minimal elements.

Example. Define a relation ![]() on

on ![]() by

by

![]()

Check each axiom for a partial order. If the axiom holds, prove it. If the axiom does not hold, give a specific counterexample.

![]() for all

for all ![]() , so

, so ![]() for all

for all ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() is reflexive.

is reflexive.

Suppose ![]() and

and ![]() . Is is true that

. Is is true that

![]() ?

?

![]() , since

, since ![]() . Likewise,

. Likewise, ![]() , since

, since ![]() . But

. But ![]() , so

, so ![]() is not antisymmetric.

is not antisymmetric.

Finally, suppose ![]() and

and ![]() . This means that

. This means that ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() , so

, so ![]() is transitive.

is transitive.![]()

Example. Define a relation ![]() on

on ![]() by

by

![]()

Check each axiom for a partial order. If the axiom holds, prove it. If the axiom does not hold, give a specific counterexample.

Since ![]() for all

for all ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

Therefore,

.

Therefore, ![]() is reflexive.

is reflexive.

![]() , since

, since ![]() . Likewise,

. Likewise, ![]() , since

, since ![]() . However,

. However, ![]() .

Therefore,

.

Therefore, ![]() is not antisymmetric.

is not antisymmetric.

Finally, suppose ![]() and

and ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() .

Therefore,

.

Therefore, ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() is transitive.

is transitive.![]()

Definition. A relation ![]() on a set X is a total order

if:

on a set X is a total order

if:

(a) (Trichotomy) For all ![]() , exactly one of the

following holds:

, exactly one of the

following holds: ![]() ,

, ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

(b) (Transitivity) For all ![]() , if

, if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

The usual less than relation ![]() is a total order on

is a total order on ![]() , on

, on ![]() , and on

, and on ![]() . Likewise, you can use the total order relation on

. Likewise, you can use the total order relation on

![]() to define a lexicographic order on

to define a lexicographic order on ![]() which is a total order.

Specifically, define a total order

which is a total order.

Specifically, define a total order ![]() on

on ![]() as follows:

as follows: ![]() means that

means that

(a) ![]() , or

, or

(b) ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

You can check that the axioms for a total order hold.

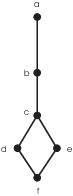

Example. Consider the relation defined by the graph below:

Thus, ![]() means that

means that ![]() , and there is an upward path of segments from x to

y.

, and there is an upward path of segments from x to

y.

Is this relation a total order? You can check cases, using the picture, that the relation is transitive. (This amounts to saying that if there's an upward path from x to y and one from y to z, then there's such a path from x to z. In fact, if you define a relation using a graph in this way, the relation will be transitive.)

However, this graph does not define a total order. Trichotomy fails

for d and e, since ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are all false.

are all false.![]()

Definition. Let S be a partially ordered set, and let T be a subset of S.

(a) ![]() is an upper bound

for T if

is an upper bound

for T if ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() is a lower bound for

T if

is a lower bound for

T if ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.

Thus, an upper bound for a subset is an element which is greater than or equal to everything in the subset; a lower bound for a subset is an element which is less than or equal to everything in the subset. Note that unlike the largest element or smallest element of a subset, upper and lower bounds don't need to belong to the subset.

For instance, consider the subset ![]() of

of ![]() . 2 is an upper bound for T, since

. 2 is an upper bound for T, since ![]() for all

for all ![]() . 1 is also an upper bound for

T. Note that 2 is not an element of T while 1 is an element of T. In

fact, any real number greater than or equal to 1 is an upper bound

for T.

. 1 is also an upper bound for

T. Note that 2 is not an element of T while 1 is an element of T. In

fact, any real number greater than or equal to 1 is an upper bound

for T.

Likewise, any real number less than or equal to 0 is a lower bound for T.

T has a largest element, namely 1. It does not have a smallest element; the obvious candidate 0 is not in T.

This example shows that a subset may have many --- even infinitely many --- upper or lower bounds. Among all the upper bounds for a set, there may be one which is smallest.

Definition. Let S be a partially ordered set,

and let T be a subset of S. An element ![]() is a least upper bound for T

if:

is a least upper bound for T

if:

(a) ![]() is an upper bound for T.

is an upper bound for T.

(b) If s is an upper bound for T, then ![]() .

.

The idea is that ![]() is an upper bound by (a); it's the

least upper bound, since (b) says

is an upper bound by (a); it's the

least upper bound, since (b) says ![]() is smaller than any other upper bound.

is smaller than any other upper bound.

Definition. Let S be a partially ordered set,

and let T be a subset of S. An element ![]() is a greatest lower bound for

T if:

is a greatest lower bound for

T if:

(a) ![]() is an lower bound for T.

is an lower bound for T.

(b) If s is an lower bound for T, then ![]() .

.

The concepts of least upper bound and greatest lower bound come up often in analysis. I'll give a simple example.

Example. Determine the least upper bound and greatest lower bound for the following sets (if they exist):

(a) The subset ![]() of

of ![]() .

.

(b) The subset ![]() of

of ![]() . (Thus, T is the positive real axis, not including

0.)

. (Thus, T is the positive real axis, not including

0.)

(a) Any real number greater than or equal to 1 is an upper bound for T. Among the upper bounds for S, it's clear that 1 is the smallest, so 1 is the least upper bound for S.

Likewise, any real number less than or equal to 0 is a lower bound for S. But among the lower bounds for S, it's clear that 0 is the largest, so 0 is the greatest lower bound for S.

Notice that ![]() , but

, but ![]() . The least upper bound and greatest lower bound may

be contained, or not contained, in the set.

. The least upper bound and greatest lower bound may

be contained, or not contained, in the set.![]()

(b) T has no least upper bound in ![]() ; in fact, T has no

upper bound in

; in fact, T has no

upper bound in ![]() .

.

0 is the greatest lower bound for T in ![]() .

.![]()

Copyright 2020 by Bruce Ikenaga