To prove a statement P by contradiction, you

assume the negation ![]() of what you want

to prove and try to derive a contradiction (usually a

statement of the form

of what you want

to prove and try to derive a contradiction (usually a

statement of the form ![]() ). Since a

contradiction is always false, your assumption

). Since a

contradiction is always false, your assumption ![]() must be false, so the original statement P must be

true.

must be false, so the original statement P must be

true.

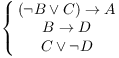

Example. Premises:

Prove: A.

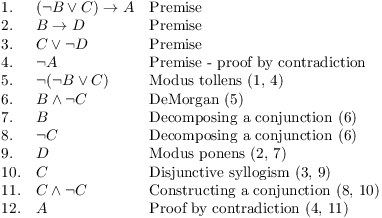

Since I want to prove A by contradiction, I begin by assuming the

negation ![]() . I'm trying to construct a

contradiction of the form

. I'm trying to construct a

contradiction of the form ![]() .

.

I arrived at the contradiction ![]() at line

11. Therefore, I conclude that my premise

at line

11. Therefore, I conclude that my premise ![]() was false, so A must be true (line 12).

was false, so A must be true (line 12).![]()

In the next example, I'll look at Euclid's proof that there are infinitely many prime numbers; it occurs in Book IX of Euclid's Elements, which was composed around 300 B.C. and is arguably the most famous math textbook of all time.

Example. Prove that there are infinitely many

prime numbers. (An integer ![]() is

prime if its only positive divisors are 1 and n.)

is

prime if its only positive divisors are 1 and n.)

Suppose that there are not infinitely many prime numbers. That means there are finitely many prime numbers --- suppose they are

![]()

Look at the number

![]()

(It's the product of all of the p's, plus one. Notice that the product of the p's wouldn't make sense if there were infinitely many p's.)

x leaves a remainder of 1 when it's divided by ![]() , since

, since ![]() divides evenly into

the

divides evenly into

the ![]() term. Likewise, x leaves a

remainder of 1 when it's divided by

term. Likewise, x leaves a

remainder of 1 when it's divided by ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() . Therefore, x is not

divisible by any of the p's --- that is, x is not divisible by any

prime number.

. Therefore, x is not

divisible by any of the p's --- that is, x is not divisible by any

prime number.

However, every integer greater than 1 is divisible by some prime number. A precise proof of this fact requires induction, which I'll discuss later. But you can see that it's reasonable. If a number z is prime, it's divisible by a prime, namely z. Otherwise, you can factor z into a product of two smaller numbers. If either factor is prime, then the prime factor is a prime which divides z. If neither factor of z is prime, you can factor them, and so on. Eventually, the process must stop, because the factors always get smaller.

Returning to my proof, I've found that x isn't divisible by any prime

number, which I've just noted is impossible. This contradiction shows

that there must be infinitely many prime numbers.![]()

Example. Prove that the following system of equations has no real solutions:

![]()

Suppose there is a real solution ![]() , so that

, so that

![]()

Add the equations, and complete the square in x:

![]()

Now squares are nonnegative, so

![]()

Also, ![]() .

.

In addition,

![]()

Therefore,

![]()

So ![]() . This

contradiction shows that the original system has no solutions.

. This

contradiction shows that the original system has no solutions.![]()

The next example is another "classical" result. The discovery that there are quantities which can't be expressed in terms of whole numbers or their ratios was known to the ancient Greeks; Boyer and Mertzbach [1] place the discovery prior to 410 B.C.

Example. Prove that ![]() is irrational. (A

rational number is a real number which can be written in the

form

is irrational. (A

rational number is a real number which can be written in the

form ![]() , where m and n are integers. A

real number which is not rational is

irrational.)

, where m and n are integers. A

real number which is not rational is

irrational.)

Suppose on the contrary that ![]() is rational. Then

I can write

is rational. Then

I can write ![]() , where

, where ![]() . (Remember that

. (Remember that ![]() stands for the set of integers.) By

dividing out any common factors, I can assume that

stands for the set of integers.) By

dividing out any common factors, I can assume that ![]() is in lowest terms (that is, m and n have

no common factors besides 1 and -1).

is in lowest terms (that is, m and n have

no common factors besides 1 and -1).

Clear the denominator, then square both sides:

![]()

Since 2 divides the left side, it must divide the right side. But if

2 divides ![]() , it must in fact divide m. So

suppose

, it must in fact divide m. So

suppose ![]() , where

, where ![]() . Substitute in the previous equation and

cancel a factor of 2:

. Substitute in the previous equation and

cancel a factor of 2:

![]()

Now 2 divides the right side, so it must divide the left side. But if

2 divides ![]() , it must divide n.

, it must divide n.

However, I already showed that 2 divides m, so 2 divides both m and

n. This contradicts my assumption that the fraction ![]() was in lowest terms.

was in lowest terms.

Therefore, ![]() must be irrational.

must be irrational.![]()

The preceding examples give situations in which proof by contradiction might be useful:

A proof by contradiction might be useful if the statement of a theorem is a negation --- for example, the theorem says that a certain thing doesn't exist, that an object doesn't have a certain property, or that something can't happen. In these cases, when you assume the contrary, you negate the original negative statement and get a positive statement, which gives you something to work with.

Having said this, I should note that it is considered bad style to write a proof by contradiction when you can give a direct proof. In those situations, the proof by contradiction often looks awkward. Moreover, the direct proof will often tell you more. For example, a direct proof that something exists will often work by constructing the object. This is better than simply knowing that the object exists on logical grounds.

In some cases, proof by contradiction is used as part of a larger proof --- for instance, to eliminate certain possibilities.

Example. Prove that the function ![]() cannot have more than one

root.

cannot have more than one

root.

In this proof, I'll use Rolle's Theorem, which

says: If f is continuous on the interval ![]() , differentiable on the interval

, differentiable on the interval ![]() , and

, and ![]() , then

, then ![]() for some

for some ![]() .

.

Suppose on the contrary that ![]() has more than one root. Then f has at least two

roots. Suppose that a and b are (different) roots of f with

has more than one root. Then f has at least two

roots. Suppose that a and b are (different) roots of f with ![]() .

.

Since f is a polynomial, it is continuous and differentiable for all x. Since a and b are roots, I have

![]()

By Rolle's Theorem, ![]() for some c such

that

for some c such

that ![]() .

.

However,

![]()

Since ![]() is a sum of even powers and a positive

number (17), it follows that

is a sum of even powers and a positive

number (17), it follows that ![]() for all x. This

contradicts

for all x. This

contradicts ![]() .

.

Therefore, f does not have more than one root.

Note: You could use the Intermediate Value Theorem to show that ![]() has at least one root. Combined with the result I

just proved, this shows that

has at least one root. Combined with the result I

just proved, this shows that ![]() has

exactly one root.

has

exactly one root.![]()

Example. On a certain island, each inhabitant always lies or always tells the truth. Calvin and Phoebe live on the island.

Calvin says: "Exactly one of us is lying."

Phoebe says: "Calvin is telling the truth."

Determine who is telling the truth and who is lying.

Suppose Calvin is a truth teller. Then "Exactly one of us is lying" is true, and since Calvin is a truth teller, Phoebe is a liar. Therefore, "Calvin is telling the truth" is a lie, so Calvin must be lying. This is a contradiction, because I assumed he was telling the truth.

Hence, I've proved by contradiction that Calvin must be a liar. Hence, "Exactly one of us is lying" is false. This gives two possibilities: Either both are telling the truth, or both are lying.

Suppose both are telling the truth. This contradicts the fact that Calvin is lying.

The only other possibility is that both are lying. Then Calvin's statement "Exactly one of us is lying" should be false (and it is), and Phoebe's statement "Calvin is telling the truth" should be false (and it is). Thus, this is the only possibility, and it's consistent with the given statements.

Therefore, Calvin and Phoebe are both liars.![]()

[1] Carl Boyer, A History of Mathematics (2![]() edition) (revised by Uta Merzbach), New

York: John Wiley \& Sons, Inc., 1991.

edition) (revised by Uta Merzbach), New

York: John Wiley \& Sons, Inc., 1991.

Copyright 2019 by Bruce Ikenaga