Continued fractions give the best rational approximations to an irrational number. In this section, we'll see in what sense this is true.

The first lemma says that the denominators of convergents of continued fractions increase.

Lemma. Let ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , ... be a sequence of integers, where

, ... be a sequence of integers, where ![]() for

for ![]() . Define

. Define

![]()

![]()

![]()

Then ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

Proof. Let ![]() . Note that

. Note that ![]() is a positive integer, and

is a positive integer, and ![]() because the a's are positive integers from

because the a's are positive integers from

![]() on. So

on. So

![]()

Theorem. Let x be irrational, and let ![]() be the k-th convergent in the

continued fraction expansion of x. Suppose

be the k-th convergent in the

continued fraction expansion of x. Suppose ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and

![]()

Then ![]() .

.![]()

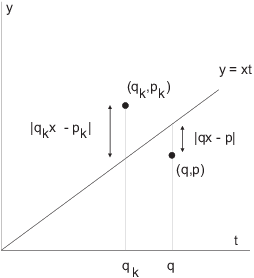

Here's what the result means. Draw the line through the origin in the

t-y plane with slope x. Plot the points ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The hypothesis ![]() says that

the vertical distance from

says that

the vertical distance from ![]() to

to ![]() is less than the vertical distance from

is less than the vertical distance from

![]() to

to ![]() .

.

The conclusion says that ![]() . In fact,

since

. In fact,

since ![]() , I have

, I have ![]() : The denominator of

: The denominator of ![]() is bigger than that of

is bigger than that of ![]() .

.

In other words, the only way the point ![]() can be closer to the line is if its

y-coordinate is bigger.

can be closer to the line is if its

y-coordinate is bigger.

Before beginning the proof, I'll note that it is a bit long and technical, though the individual steps aren't hard. I've tried to write out the details carefully, but if the informal discussion above gives you enough of an idea of what the theorem says, you could skip the proof and come back to it later if needed.

Proof. I'll give a proof by contradiction.

Suppose that ![]() .

.

Consider the equations

![]()

u and v are defined as the solutions to these equations.

Think of this in matrix form:

![]()

Using an earlier result on convergents, the determinant of the coefficient matrix is

![]()

This means that when I solve the matrix equation by inverting the coefficient matrix, I get

![]()

The point is that u and v are integers.

I'll now establish the contradiction in a series of steps.

Step 1. ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() gives

gives ![]() , so

, so

![]()

Also, ![]() gives

gives ![]() , so

, so

![]()

That is,

![]()

Thus, ![]() . But

. But ![]() (as

(as ![]() and

and ![]() are the numerator and the denominator of a

convergent), so

are the numerator and the denominator of a

convergent), so ![]() . This is

a contradiction, because I'm assuming that

. This is

a contradiction, because I'm assuming that ![]() . This proves that

. This proves that ![]() .

.

Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() gives

gives ![]() . Also,

. Also, ![]() gives

gives ![]() . Hence,

. Hence,

This implies ![]() , which contradicts

, which contradicts ![]() established above. Hence,

established above. Hence, ![]() .

.

Step 2. u and v have opposite signs.

Since ![]() , either

, either ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , so

, so

![]()

Then ![]() gives

gives

![]()

Since ![]() , I must have

, I must have ![]() . Hence, u and v have opposite signs in

this case.

. Hence, u and v have opposite signs in

this case.

Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore,

![]()

Since ![]() , I have

, I have ![]() . Hence, u and v have opposite signs in

this case.

. Hence, u and v have opposite signs in

this case.

Step 3. ![]() and

and ![]() have opposite signs.

have opposite signs.

The value x of the infinite continued fraction lies between any two consecutive convergents. Hence, either

![]()

If ![]() , the first inequality gives

, the first inequality gives ![]() , so

, so ![]() . The second inequality gives

. The second inequality gives ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() and

and ![]() have opposite signs in this

case.

have opposite signs in this

case.

If ![]() , the first inequality gives

, the first inequality gives ![]() , so

, so ![]() . The second inequality

gives

. The second inequality

gives ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() and

and ![]() have opposite signs in this

case.

have opposite signs in this

case.

Step 4. ![]() and

and ![]() have the same sign.

have the same sign.

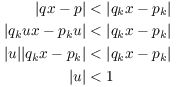

This follows from Steps 2 and 3 by checking the possible combinations of (opposite) signs:

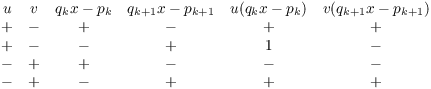

Step 5. (Final contradiction) Since ![]() and

and ![]() have the same sign,

have the same sign,

![]()

Therefore, using the defining equations for u and v to substitute for p and q, I get

It has been a while, but you may still remember that a hypothesis of

this theorem was ![]() . So we have our contradiction, and it follows that

. So we have our contradiction, and it follows that ![]() .

.![]()

Corollary. Let x be irrational, and let ![]() be the k-th

convergent in the continued fraction expansion of x. Suppose

be the k-th

convergent in the continued fraction expansion of x. Suppose ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and

![]()

Then ![]() .

.

Proof. Given the hypotheses of the corollary,

suppose on the contrary that ![]() . Multiply this inequality by

. Multiply this inequality by

![]()

I get

![]()

Apply the theorem to obtain ![]() . But then

. But then ![]() , which contradicts the fact that

the q's increase.

, which contradicts the fact that

the q's increase.

Therefore, ![]() .

.![]()

This result says that the only way a rational number ![]() can approximate a continued fraction

better than a convergent

can approximate a continued fraction

better than a convergent ![]() is if the fraction has a bigger

denominator than the convergent.

is if the fraction has a bigger

denominator than the convergent.

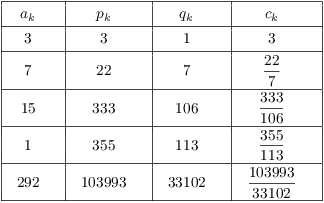

For example, consider the convergents for the continued fraction

expansion of ![]() :

:

![]() , which is

in error in the seventh place. The theorem says that a fraction

, which is

in error in the seventh place. The theorem says that a fraction ![]() can be closer to

can be closer to ![]() than

than ![]() only if

only if

![]() .

.

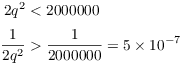

The next result is sort of a converse to the previous two results. It says that if a rational number approximates an irrational number x "sufficiently well", then the rational number must be a convergent in the continued fraction expansion for x.

Theorem. Let x be irrational, and let ![]() be a rational number in lowest terms with

be a rational number in lowest terms with

![]() . Suppose that

. Suppose that

![]()

Then ![]() is a

convergent in the continued fraction expansion for x.

is a

convergent in the continued fraction expansion for x.

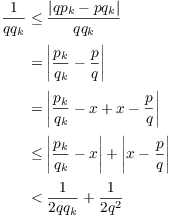

Proof. Since ![]() for

for ![]() , the q's form a strictly increasing

sequence of positive integers. Therefore, for some k,

, the q's form a strictly increasing

sequence of positive integers. Therefore, for some k,

![]()

Since ![]() , the contrapositive of

the preceding theorem gives

, the contrapositive of

the preceding theorem gives

![]()

Hence,

![]()

Now assume toward a contradiction that ![]() is not a convergent in the

continued fraction expansion for x. In particular,

is not a convergent in the

continued fraction expansion for x. In particular, ![]() , so

, so ![]() , and hence

, and hence ![]() is a positive integer.

is a positive integer.

Since ![]() ,

,

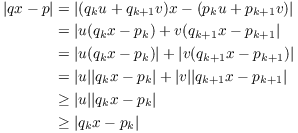

(The second inequality comes from the Triangle Inequality: ![]() .)

.)

Subtracting ![]() from

both sides, I get

from

both sides, I get

But I assumed ![]() , so this is a

contradiction.

, so this is a

contradiction.

Therefore, ![]() is a

convergent in the continued fraction expansion for x.

is a

convergent in the continued fraction expansion for x.![]()

Example. Show that ![]() is the best rational approximation

to

is the best rational approximation

to ![]() by a fraction having a denominator less than

1000.

by a fraction having a denominator less than

1000.

Suppose that ![]() is a fraction

in lowest terms that is a better approximation to

is a fraction

in lowest terms that is a better approximation to ![]() than

than ![]() , and

that

, and

that ![]() .

.

Since ![]() is a fraction

is a better approximation to

is a fraction

is a better approximation to ![]() than

than ![]() ,

,

![]()

Since ![]() ,

,

But

![]()

Thus,

![]()

The hypotheses of the theorem are satisfied, so ![]() must be a convergent in the continued

fraction expansion of

must be a convergent in the continued

fraction expansion of ![]() .

.

But the other convergents with denominators less than 1000 --- 3,

![]() ,

, ![]() --- with denominators less than

1000 are poorer approximations to

--- with denominators less than

1000 are poorer approximations to ![]() than

than ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() is the

best rational approximation to

is the

best rational approximation to ![]() by a fraction having a denominator less than

1000.

by a fraction having a denominator less than

1000.![]()

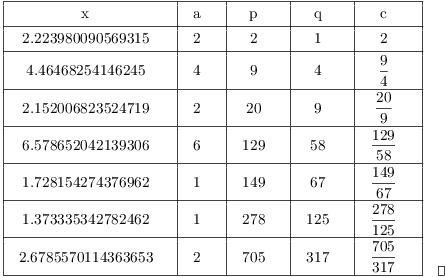

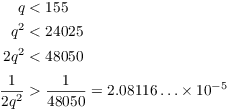

Example. (a) Compute the first 6 convergents

![]() , ...

, ... ![]() of the continued fraction for

of the continued fraction for ![]() .

.

(b) Show that ![]() is the

best rational approximation to

is the

best rational approximation to ![]() having denominator less than 155.

having denominator less than 155.

(a)

(b) Suppose that ![]() is a fraction

in lowest terms which is a better approximation to

is a fraction

in lowest terms which is a better approximation to ![]() than

than ![]() , and also that

, and also that ![]() .

.

Since ![]() is a better

approximation to

is a better

approximation to ![]() than

than ![]() ,

,

![]()

Since ![]() ,

,

So I have

![]()

(The inequalities are approximate, but there is enough room between

![]() and

and ![]() that there is no

problem.)

that there is no

problem.)

By the approximation theorem, ![]() is a convergent for

is a convergent for ![]() . But no convergent with

. But no convergent with ![]() is a better approximation than

is a better approximation than ![]() .

.

This contradiction shows that ![]() is the best rational approximation

to

is the best rational approximation

to ![]() having denominator less than

155.

having denominator less than

155.![]()

Copyright 2019 by Bruce Ikenaga