If n and k are integers, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , then the binomial

coefficient

, then the binomial

coefficient ![]() (read n-choose-k) is defined

by

(read n-choose-k) is defined

by

![]()

Why "n-choose-k"? Suppose you have n different objects. How many ways are there of choosing k of them (without worrying about the order of choice)?

The first object can be chosen in n ways. Then there are ![]() objects left, so the second can be chosen in

objects left, so the second can be chosen in ![]() ways. Then there are

ways. Then there are ![]() objects left, so the third can be chosen in

objects left, so the third can be chosen in ![]() ways. And so on. At the

ways. And so on. At the ![]() choice, you have

choice, you have ![]() objects to choose from. So the number of

ways of choosing k objects in a particular order is

objects to choose from. So the number of

ways of choosing k objects in a particular order is

![]()

However, since I don't care about the order in which I choose the k

objects (only which k objects are chosen), I have to divide by the

number of different orders in which I could have chosen the k

objects. This is the number of permutations of k objects, which is

![]() . Hence, the number of ways of choosing k objects

from a set of n, without regard for order, is

. Hence, the number of ways of choosing k objects

from a set of n, without regard for order, is

![]()

Example. Compute ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

Proposition. ( Properties of binomial coefficients)

(a) ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() .

.

(c) ( Pascal's triangle) ![]() .

.

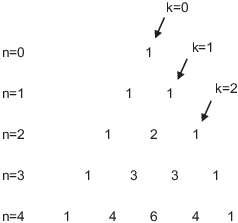

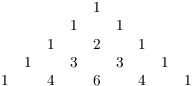

The last property has the following pictorial interpretation.

Make a triangle as shown by starting at the top and writing 1's down

the sides. Then fill in the middle of the triangle one row at a time,

by adding the elements diagonally above the new element. For example,

the leftmost 4 in the ![]() row was obtained this way:

row was obtained this way:

![]()

The formula above is simply an algebraic expression of this addition procedure.

Proof. You can check the formulas in (a) and (b) by writing out the binomial coefficients. Here's the computation for one part of (a):

![]()

And here's the computation for (b):

![]()

The proof of (c) is also a computation, though it's a little more involved:

![]()

![]()

Of course, binomial coefficients get their name because they're the coefficients in the expansion of a binomial:

![]()

Since the coefficients can be read off from Pascal's triangle, you can use the triangle to write down binomial expansions.

Example. Use Pascal's triangle to compute the

binomial expansion of ![]() .

.

Using the ![]() row in the triangle, I get

row in the triangle, I get

![]()

Example. Determine the coefficient of ![]() in the expansion of

in the expansion of ![]() .

.

The term containing ![]() is

is

![]()

(I cancelled the ![]() with the first 37 terms in

with the first 37 terms in ![]() , then cancelled the

, then cancelled the ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() .) The coefficient is

.) The coefficient is ![]() , or

-36663215228190720 if you multiply it out.

, or

-36663215228190720 if you multiply it out.![]()

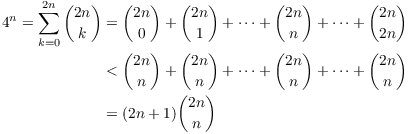

Example. Prove that

![]()

Some results involving binomial coefficients can be proven by

choosing an appropriate binomial expansion. In this case, I notice

that the "![]() " in the binomial coefficient

would come from expanding

" in the binomial coefficient

would come from expanding ![]() . But what

should I choose for x and y?

. But what

should I choose for x and y?

After some trial and error, I find that this works:

![]()

The binomial coefficient ![]() is the middle term in this sum --- but being the

middle term, it is also the largest term in the sum. Look at

Pascal's Triangle to convince yourself that this is true:

is the middle term in this sum --- but being the

middle term, it is also the largest term in the sum. Look at

Pascal's Triangle to convince yourself that this is true:

There are ![]() terms in the sum, and all of them

are less than

terms in the sum, and all of them

are less than ![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

Dividing both sides by ![]() , I get

, I get

![]()

Copyright 2019 by Bruce Ikenaga