Definition. The sum of divisors function is given by

![]()

As usual, the notation "![]() " as the

range for a sum or product means that d ranges over the positive divisors of n.

" as the

range for a sum or product means that d ranges over the positive divisors of n.

The number of divisors function is given by

![]()

For example, the positive divisors of 15 are 1, 3, 5, and 15. So

![]()

I want to find formulas for ![]() and

and ![]() in terms of the prime factorization of n. This will

be easy if I can show that

in terms of the prime factorization of n. This will

be easy if I can show that ![]() and

and ![]() are multiplicative. I can do most of the work in the

following theorem.

are multiplicative. I can do most of the work in the

following theorem.

Theorem. The divisor sum of a multiplicative function is multiplicative.

Proof. Suppose f is multiplicative, and let

![]() be the divisor sum of f. Suppose

be the divisor sum of f. Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Then

\cdot [D(f)](n) = \left(\sum_{a \mid m} f(a)\right) \left(\sum_{b \mid n} f(b)\right) = \sum_{a \mid m} \sum_{b \mid n} f(a)f(b).$$](divisor-functions12.png)

Now ![]() , so if

, so if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() . Therefore,

multiplicativity of f implies

. Therefore,

multiplicativity of f implies

![]()

Now every divisor d of ![]() can be written as

can be written as ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() . Going the other way, if

. Going the other way, if ![]() and

and ![]() then

then ![]() . So I may set

. So I may set ![]() , where

, where ![]() , and replace the double sum with a single sum:

, and replace the double sum with a single sum:

![]()

This proves that ![]() is multiplicative.

is multiplicative.![]()

Theorem. (a) The sum of divisors function ![]() is multiplicative.

is multiplicative.

(b) The number of divisors function ![]() is multiplicative.

is multiplicative.

Proof. (a) The identity function ![]() is multiplicative:

is multiplicative: ![]() for all m, n, so obviously it's true for

for all m, n, so obviously it's true for

![]() . Therefore, the divisor sum of

. Therefore, the divisor sum of ![]() is multiplicative. But

is multiplicative. But

![]()

Hence, the sum of divisors function ![]() is multiplicative.

is multiplicative.

(b) The constant function ![]() is

multiplicative:

is

multiplicative: ![]() for

all m, n, so obviously it's true for

for

all m, n, so obviously it's true for ![]() . Therefore, the divisor sum of I is multiplicative.

But

. Therefore, the divisor sum of I is multiplicative.

But

![]()

Hence, the number of divisors function ![]() is multiplicative.

is multiplicative.![]()

I'll use multiplicativity to obtain formulas for ![]() and

and ![]() in terms of their

prime factorizations (as I did with

in terms of their

prime factorizations (as I did with ![]() ). First, I'll get the formulas in the case where n

is a power of a prime.

). First, I'll get the formulas in the case where n

is a power of a prime.

Lemma. Let p be prime.

(a) ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() .

.

Proof. The divisors of ![]() are 1, p,

are 1, p, ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() . So the sum of the divisors is

. So the sum of the divisors is

![]()

And since the divisors of ![]() are 1, p,

are 1, p, ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() , there are

, there are ![]() of them, and

of them, and

![]()

Theorem. Let ![]() , where the p's are distinct

primes and

, where the p's are distinct

primes and ![]() for all i. Then:

for all i. Then:

![]()

![]()

Proof. These results follow from the preceding

lemma, the fact that ![]() and

and ![]() are multiplicative, and the fact that the prime power

factors

are multiplicative, and the fact that the prime power

factors ![]() are pairwise relatively prime.

are pairwise relatively prime.![]()

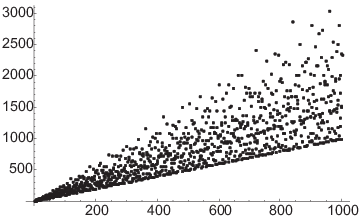

Here is a graph of ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

Note that if p is prime, ![]() . This

gives the point

. This

gives the point ![]() , which lies on the line

, which lies on the line ![]() . This is the line that you see bounding the dots

below.

. This is the line that you see bounding the dots

below.

For each n, there are only finitely many numbers k whose divisor sum

is equal to n: that is, such that ![]() . For k

divides itself, so

. For k

divides itself, so

![]()

This says that k must be less than n. So if I'm looking for numbers

whose divisors sum to n, I only need to look at numbers less than n.

For example, if I want to find all numbers whose divisors sum to 42,

I only need to look at ![]() .

.

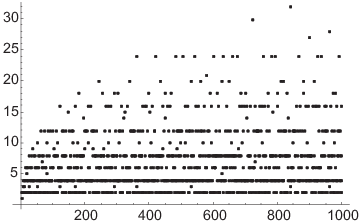

Here is a graph of ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

If p is prime, ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() repeatedly returns to the horizontal line

repeatedly returns to the horizontal line ![]() , which you can see bounding the dots below.

, which you can see bounding the dots below.

The formulas given in the theorem allow us to compute ![]() and

and ![]() by hand for at

least small values of n. For example,

by hand for at

least small values of n. For example, ![]() , so

, so

![]()

![]()

Example. Find all positive integers n such

that ![]() .

.

Since ![]() doesn't work, I can assume

doesn't work, I can assume ![]() .

.

I have

![]()

In other words, ![]() is a sum of distinct positive integers other than 1

and n that is equal to 7. I have to consider all possible ways of

doing this. I'll consider cases according to the largest element of

this sum, which is the largest divisor d of n other than 1 and n.

is a sum of distinct positive integers other than 1

and n that is equal to 7. I have to consider all possible ways of

doing this. I'll consider cases according to the largest element of

this sum, which is the largest divisor d of n other than 1 and n.

Suppose ![]() .

.

![]()

Then the only divisor of n other than 1 and n is 7. Since ![]() , I know

, I know ![]() for

for ![]() . But if

. But if ![]() , then 49 would be a divisor

of n other than 1 and n. Hence,

, then 49 would be a divisor

of n other than 1 and n. Hence, ![]() , and this is a

solution.

, and this is a

solution.

Suppose ![]() . Then the expression

. Then the expression ![]() must have the form

must have the form

![]() , which contradicts the assumption that the sum does

not include 1.

, which contradicts the assumption that the sum does

not include 1.

Suppose ![]() . Then the expression

. Then the expression ![]() must have the form

must have the form

![]() . In this case,

. In this case, ![]() .

.

Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

But if ![]() , then

, then ![]() . So

. So ![]() must have the form

must have the form ![]() , contradicting the assumption that the sum does not

include 1.

, contradicting the assumption that the sum does not

include 1.

Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

However, ![]() can't include 1,

and can't use 2 twice. Hence, this isn't possible.

can't include 1,

and can't use 2 twice. Hence, this isn't possible.

Suppose ![]() . Then the remaining terms in

. Then the remaining terms in ![]() must sum to 5

and can only use 1, which is excluded by assumption. Hence, this

isn't possible.

must sum to 5

and can only use 1, which is excluded by assumption. Hence, this

isn't possible.

Therefore, ![]() or

or ![]() .

.![]()

Copyright 2019 by Bruce Ikenaga