In this section, I'll give proofs of some of the properties of limits. This section is pretty heavy on theory --- more than I'd expect people in a calculus course to know. So unless you're reading this section to learn about analysis, you might skip it, or just look at the statements of the results and the examples.

First, let's recall the ![]() definition

of a limit.

definition

of a limit.

Definition. Let f be a real-valued function

defined on an open interval containing a point ![]() , but possibly not at c. If

, but possibly not at c. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() means: For every

means: For every ![]() , there is a

, there is a

![]() such that for every x in the domain of f,

such that for every x in the domain of f,

![]()

Informally, "making x close to c makes ![]() close to L". In this section, I'll prove various

results for computing limits. But I'll begin with an example which

shows that the limit of a function at a point does not have to be

defined.

close to L". In this section, I'll prove various

results for computing limits. But I'll begin with an example which

shows that the limit of a function at a point does not have to be

defined.

In the next example and in several of the proofs below, I'll need to use the Triangle Inequality. It says that if p and q are real numbers, then

![]()

You often use the Triangle Inequality to combine absolute value terms (going from the left side to the right side) or to break up an absolute value term (going from the right side to the left side).

Example. ( A limit that is undefined) Let

![]()

Prove that

![]()

Suppose on the contrary that

![]()

This means that for every ![]() , there is a

, there is a

![]() such that

such that

![]()

(In this case, the "c" of the definition is equal to 0.)

Choose ![]() . I'll that there

is no number

. I'll that there

is no number ![]() such that if

such that if ![]() , then

, then

![]()

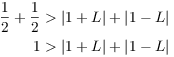

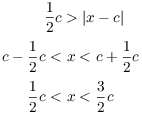

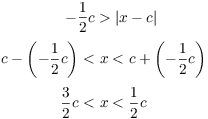

Suppose there is such a number ![]() . The x's which satisfy the inequality

. The x's which satisfy the inequality ![]() are the points in the interval

are the points in the interval ![]() . Note that there are both positive and

negative numbers in this interval.

. Note that there are both positive and

negative numbers in this interval.

Let a be a positive number in ![]() .

Since

.

Since ![]() , I have

, I have ![]() , so

, so

![]()

Let b be a negative number in ![]() .

Since

.

Since ![]() , I have

, I have ![]() , so

, so

![]()

Note that

![]()

So I can write my two inequalities like this:

![]()

Add the two inequalities:

By the Triangle Inequality,

![]()

Combining this with ![]() , I get

, I get

![]()

This is a contradiction. Therefore, my assumption that ![]() is defined must be incorrect, and

the limit is undefined.

is defined must be incorrect, and

the limit is undefined.![]()

Proposition. ( The limit of a

constant) Let ![]() and

and ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

In other words, the limit of a constant is the constant.

Proof. In this case, the function is ![]() and the limit is

and the limit is ![]() .

.

Let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Since the conclusion of the statement "If ![]() , then

, then ![]() " is true, the statement is true regardless of what

" is true, the statement is true regardless of what ![]() is. (For the sake of definiteness, I could choose

is. (For the sake of definiteness, I could choose

![]() , for example.) This proves that

, for example.) This proves that ![]() .

.![]()

Proposition. Let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Proof. In this case, the function is ![]() and the limit is

and the limit is ![]() .

.

Let ![]() . Set

. Set ![]() .

Suppose

.

Suppose ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , I have

, I have

![]()

This proves that ![]() .

.![]()

Theorem. ( The limit of a

sum) Let ![]() . Let f and g be functions defined

on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c. Suppose that

. Let f and g be functions defined

on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c. Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. Let ![]() . I need to

find a number

. I need to

find a number ![]() such that

such that

![]()

The idea is that since ![]() , I can force

, I can force ![]() to be close to L, and

since

to be close to L, and

since ![]() , I can force

, I can force ![]() to be close to M. Since I want

to be close to M. Since I want ![]() to be within

to be within ![]() of

of ![]() , I'll split the difference: I'll force

, I'll split the difference: I'll force ![]() to be within

to be within ![]() of L

and force

of L

and force ![]() to be within

to be within ![]() of M.

of M.

First, ![]() means that I can

find a number

means that I can

find a number ![]() such that

such that

![]()

Likewise, ![]() means that I can

find a number

means that I can

find a number ![]() such that

such that

![]()

I'd like to choose ![]() so that both of these hold. To do

this, I'll let

so that both of these hold. To do

this, I'll let ![]() be the

smaller of

be the

smaller of ![]() and

and ![]() . (If

. (If ![]() and

and ![]() are equal, I choose

are equal, I choose ![]() to be their common

value.) The mathematical notation for this is

to be their common

value.) The mathematical notation for this is

![]()

Since ![]() is the smaller of

is the smaller of ![]() and

and ![]() , it must be at

least as small as both:

, it must be at

least as small as both:

![]()

Now suppose ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() ,

,

![]()

Therefore,

![]()

Since ![]() ,

,

![]()

Therefore,

![]()

Add the inequalities ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

By the Triangle Inequality,

![]()

Combining this with ![]() , I get

, I get

![]()

This proves that ![]() .

.![]()

Remark. This result is often written as

![]()

But it's important to understand that the equation is true provided that the limits on the right side are defined. If they are not, then the result might be false. For example, let

![]()

In an earlier example, I showed that ![]() is undefined. Since

is undefined. Since ![]() , essentially

the same proof as in the example shows that

, essentially

the same proof as in the example shows that ![]() is undefined. However,

is undefined. However,

![]()

Hence, the limit-of-a-constant rule shows that

![]()

In this case, the equation

![]()

The left side is 0, while the right side is undefined.![]()

Remark. The rule for sums holds for a sum of more than 2 terms. Without writing out all the hypotheses, it says

![]()

The proof uses mathematical induction; I won't write it out, though it isn't that difficult. I will, however, use this result in proving the rule for limits of polynomials.

Having just proved a limit rule for sums, it's natural to try to prove a similar rule for products. With the appropriate fine print, it should say that

![]()

If you try to write a proof for this, you might find it a bit more challenging than the ones I've done so far. While it's possible to write a direct proof, some of the ones I've seen look a bit magical: They're shorter than the approach I'll take, but it can be hard to see how someone thought of them.

So instead, I'll take a different approach, which is often useful in writing proofs in math: If your proof looks too difficult, try to prove a special case first. I'll get a bunch of special cases (which are useful in their own rights), and whose proofs are fairly straightforward.

I'll begin with the special case where one of the functions in the product is just a constant.

Theorem. ( Multiplication by

constants) Let ![]() . Let f be a function

defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c.

Suppose that

. Let f be a function

defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c.

Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. First, if ![]() , then the limit-of-a-constant rule says

, then the limit-of-a-constant rule says

![]()

But ![]() , so desired equation holds:

, so desired equation holds:

![]()

Having dealt with the case ![]() , I'll assume

, I'll assume ![]() .

.

Let ![]() . By assumption,

. By assumption,

![]()

Hence, I may find ![]() so that if

so that if ![]() , then

, then

![]()

(Notice that I'm not dividing by 0 on the left side, because ![]() .)

.)

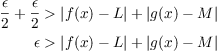

With this value of ![]() , I have that

, I have that ![]() implies

implies

![$$\eqalign{ \dfrac{\epsilon}{|k|} & > |f(x) - L| \cr \noalign{\vskip2pt} \epsilon & > |k| \cdot |f(x) - L| \cr \epsilon & > |[k \cdot f(x)] - (k \cdot L)| \cr}$$](limit-theorems136.png)

This proves that

![]()

Remark. This rule is often written more concisely as

![]()

The multiplication-by-constants rule is a special case of the general rule for products that I'd like to prove, but it's useful in its own right. Here are two easy consequences.

Corollary. ( Negatives)

Let ![]() . Let f be a function defined on an open

interval containing c, but possibly not at c. Suppose that

. Let f be a function defined on an open

interval containing c, but possibly not at c. Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. Take ![]() in the

multiplication-by-constants rule.

in the

multiplication-by-constants rule.![]()

Corollary. ( The limit of a

difference) Let ![]() . Let f and g be functions

defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c.

Suppose that

. Let f and g be functions

defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c.

Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. By the preceding corollary, I have

![]()

Therefore, by the rule for sums,

![]()

Here's another special case of the limit of a product.

Lemma. ( Product of zero

limits) Let ![]() . Let f and g be functions defined

on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c. Suppose that

. Let f and g be functions defined

on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c. Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. Let ![]() . I need to

find a number

. I need to

find a number ![]() such that

such that

![]()

The idea is that I can "control" ![]() and

and ![]() , so I'll try to get two

inequalities

, so I'll try to get two

inequalities ![]() and

and ![]() which multiply to

which multiply to ![]() . Since the problem seems to be "symmetric"

in f and g, it's natural to use

. Since the problem seems to be "symmetric"

in f and g, it's natural to use ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , I may find a

number

, I may find a

number ![]() such that if

such that if ![]() , then

, then

![]()

Since ![]() , I may find a

number

, I may find a

number ![]() such that if

such that if ![]() , then

, then

![]()

Now let ![]() . Then

if

. Then

if ![]() , I have both

, I have both ![]() and

and ![]() .

Thus,

.

Thus,

![]()

Multiplying the last two inequalities, I get

![]()

This proves that ![]() .

.![]()

You can consider the next lemma an example of how you might use the preceding results.

Lemma. Let ![]() . Let f be a

function defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not

at c. Suppose that

. Let f be a

function defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not

at c. Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof.

![$$\matrix{ \lim_{x \to c} [f(x) - L] & = & \lim_{x \to c} f(x) - \lim_{x \to c} L & \hbox{(Limit of a difference)} \hfil \cr & = & L - L & \hbox{(Given limit, limit of a constant)} \hfil \cr & = & 0 & \cr} \quad\halmos$$](limit-theorems178.png)

Now I'll put together a lot of the previous results to prove the rule

for the limit of a product. I actually don't need an ![]() proof in this case: Just the earlier rules

and some careful algebra.

proof in this case: Just the earlier rules

and some careful algebra.

Theorem. ( The limit of a

product) Let ![]() . Let f and g be functions

defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c.

Suppose that

. Let f and g be functions

defined on an open interval containing c, but possibly not at c.

Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

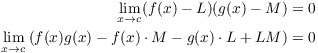

Proof. Suppose that

![]()

By the last lemma,

![]()

I apply the product of zero limits lemma and multiply out the factors in the limit:

(Save this huge expression for a second.)

Now by the rules for multiplication by constants and the limit of a constant,

![]()

By the rules for the limit of a sum and a difference,

![]()

So again by the rule for the limit of a sum (I'm adding the big expression in the line above, and the big expression two lines above),

![]()

![]()

But (cancelling 6 terms)

![]()

So

![]()

Remark. I had to be careful in using the rule for the limit of a sum to ensure that the component limits were defined before applying the rule. That is why I couldn't simply apply it to the left side of

![]()

To apply the sum rule to the left side, I would need to know that

![]() exists, but that is

part of what I was trying to prove.

exists, but that is

part of what I was trying to prove.

You might want to look up the shorter, "magical" proofs of the rule for the Limit of a Product and see if you like them better than this approach.

Remark. The rule for products holds for a product of more than 2 terms. Without writing out all the hypotheses, it says

![]()

The proof uses mathematical induction; I won't write it out, though it isn't that difficult.

My next goal is to prove that if ![]() is a polynomial, then

is a polynomial, then

![]()

I'll prove it by putting together some preliminary results. Let's start with a really easy one.

Lemma.

![]()

Proof. Let ![]() . I have to

find

. I have to

find ![]() so that if

so that if ![]() ,

then

,

then ![]() . Just take

. Just take ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Proposition. ( Powers)

If n is an integer and ![]() , then

, then

![]()

This proof will use mathematical induction. Explaining induction here would require a separate and fairly lengthy discussion, so I'll just give the proof and assume that you've seen induction elsewhere. Or you can just take this result for granted, since it's not very surprising.

Proof. For ![]() , the left side is

(by the constants rule)

, the left side is

(by the constants rule)

![]()

The right side is ![]() . The left and right sides are

equal, and the result is true for

. The left and right sides are

equal, and the result is true for ![]() .

.

Assume that ![]() and the result holds for n:

and the result holds for n:

![]()

I will prove it for ![]() :

:

![]()

The first and last equalities just used rules for powers. The second equality used the rule for the limit of a product. The third equality used the induction assumption and the previous lemma.

This proves the result for ![]() , so the result holds for all

, so the result holds for all

![]() by induction.

by induction.![]()

Remark. The rule for powers holds for negative integer powers. It also holds for rational number powers (with suitable restrictions --- you can't take the square root of a negative number, for instance) and even real number powers. I'll prove some of this below, but the there's an easier way to do all of these at once The idea is that if r is a real number, I can write

![]()

Then I'll need to use limit results on the natural log and exponential functions. That will require a discussion of those functions, which we'll have later.

Theorem. ( Polynomials)

Let ![]() ,

, ![]() , ...

, ... ![]() ,

, ![]() be real numbers. Consider the

polynomial

be real numbers. Consider the

polynomial

![]()

Then

![]()

In other words, if ![]() is a polynomial, then

is a polynomial, then

![]()

Proof. By the rules for multiplication by

constants and powers, for ![]() , ... n, I have

, ... n, I have

![]()

Then by the rule for sums (which I remarked holds for a sum with any number of terms),

![]()

Example. Compute ![]() .

.

By the rule for polynomials, I can just plug 3 in for x:

![]()

We'll see that other functions have the property that you can compute

![]() by "plugging in c for

x". The property is called continuity.

by "plugging in c for

x". The property is called continuity.

You might expect that there would be a rule that says "the limit

of a quotient is the quotient of the limits". There is ---

though we have to be careful that the component limits exist, and

also that we avoid division by 0. As with the rule for products, you

can give a proof which looks a little "magical" --- but

instead, as I did with the rule for products, I'll derive the rule

for quotients from some other rules which are independently useful.

There's still a little "magic" in the proof of the lemma

for ![]() , but it's not

too bad if you work backwards "on scratch paper" first.

, but it's not

too bad if you work backwards "on scratch paper" first.

Lemma. Suppose that ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Proof. ( Scratch work.) Before I do the real proof, I do some scratch work so the actual work doesn't seem too magical. This is going to get a little wordy, so if you're not interested, you could just skip to the real proof below.

As is common with limit proofs, I work backwards from what I want.

According to the ![]() definition, I want

definition, I want

![]()

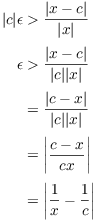

Now ![]() , so

, so ![]() "controls"

"controls" ![]() . I'll do some

algebra to try to get a factor of

. I'll do some

algebra to try to get a factor of ![]() :

:

![]()

I combined the fractions over a common denominator, then broke the

result up into three factors. Note that ![]() , because the absolute value of a number

equals the absolute value of its negative.

, because the absolute value of a number

equals the absolute value of its negative.

The first factor ![]() is a

constant, so I don't need to worry about it. The third factor is

is a

constant, so I don't need to worry about it. The third factor is ![]() , which I can control using

, which I can control using ![]() .

.

In order to get some control over the second factor ![]() , I make a preliminary setting of

, I make a preliminary setting of ![]() . This isn't a problem, since intuitively I have

complete control over

. This isn't a problem, since intuitively I have

complete control over ![]() . (You'll see how this works out

in the real proof.) But how should I set

. (You'll see how this works out

in the real proof.) But how should I set ![]() ?

?

I don't want ![]() to get too big. But if x is close

to 0, then

to get too big. But if x is close

to 0, then ![]() will be large --- for example,

will be large --- for example,

![]() . So I want to set

. So I want to set ![]() so that x doesn't get too close to 0.

so that x doesn't get too close to 0.

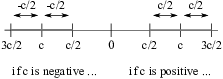

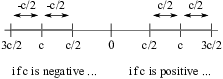

![]() controls how close x is to c. And I'm given that

controls how close x is to c. And I'm given that ![]() . So by forcing x to be close enough to c, I can

force x to stay away from 0. There are lots of ways to do this; this

picture shows what I will do.

. So by forcing x to be close enough to c, I can

force x to stay away from 0. There are lots of ways to do this; this

picture shows what I will do.

As the picture shows, I'll force x to stay within ![]() of c. I can do this by setting

of c. I can do this by setting ![]() .

.

There are two cases, depending on whether c is positive or negative,

but you can see the cases are symmetric. x will lie in an interval

around c, and it won't get any closer to 0 than ![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

![]()

Taking reciprocals,

![]()

Now putting this back into the expression above,

![]()

I want the left-hand expression to be less than ![]() . If the right-hand expression is less than

. If the right-hand expression is less than ![]() , this will be true:

, this will be true:

![]()

So how can I make ![]() ? Moving the first two terms to the right,

I get

? Moving the first two terms to the right,

I get

![]()

But I can control ![]() directly using

directly using ![]() , so I can make this happen if

, so I can make this happen if ![]() .

.

Now earlier, I made a preliminary setting of ![]() . I seem to have two settings for

. I seem to have two settings for

![]() . There is a standard trick for getting both of these

at once: Set

. There is a standard trick for getting both of these

at once: Set ![]() to the smaller of the two. The

notation for this is

to the smaller of the two. The

notation for this is

![]()

Since ![]() is the smaller of the two, I get

is the smaller of the two, I get

![]()

I arrived at my guess for ![]() by working

backwards. I have to write the real proof forwards, starting with my

guess for

by working

backwards. I have to write the real proof forwards, starting with my

guess for ![]() . Here it is.

. Here it is.

( Real proof.) Let ![]() . Set

. Set ![]() . Suppose

. Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Consider the first inequality ![]() . This means that x is less than

. This means that x is less than ![]() from c. So if c is positive, then

from c. So if c is positive, then

And if c is negative, then ![]() , so

, so

In both cases,

Multiply ![]() and

and ![]() to get

to get

This proves that ![]() .

.![]()

The next theorem is important in its own right.

Theorem. ( Composites)

Let ![]() . Suppose that:

. Suppose that:

(a) f is a function defined on an open interval containing a, but possibly not at a.

(b) ![]() .

.

(c) g is a function defined on an open interval containing b, but possibly not at b.

(d) ![]() .

.

Then

![]()

To write it somewhat roughly,

![]()

Proof. Let ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , I can find a number

, I can find a number ![]() such that if

such that if ![]() ,

then

,

then ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , I can find a

number

, I can find a

number ![]() such that if

such that if ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

Suppose that ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() . But then

. But then

![]()

This proves that ![]() .

.![]()

Example. Compute ![]() .

.

Let

![]()

Then

![]()

By the rules for limits of polynomials and composites,

![]()

Theorem. ( Reciprocals) Suppose f is a function defined on an open interval containing a, but possibly not at a, and

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. Let ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Since ![]() , it follows that g is defined on an open

interval containing L,

, it follows that g is defined on an open

interval containing L,

Since ![]() , the

, the ![]() -lemma

implies that

-lemma

implies that

![]()

Then the rule for composites implies that

![]()

Theorem. ( Quotients) Suppose f and g are functions defined on an open interval containing a, but possibly not at a. Suppose that

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. Note that ![]() , and that by

the reciprocal rule

, and that by

the reciprocal rule

![]()

Then by the rule for products,

![]()

Example. Compute ![]() .

.

By the rules for limits of polynomials and quotients,

![]()

The next result is different from the previous results, in that the statement doesn't seem obvious at first glance. However, the conclusion is reasonable if you draw a picture

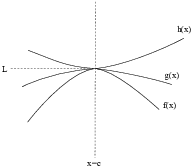

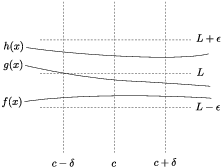

Theorem. ( The Squeezing

Theorem) Suppose ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are defined on a open interval I containing c, but

are not necessarily defined at c. Assume that

are defined on a open interval I containing c, but

are not necessarily defined at c. Assume that

![]()

![]()

Then

![]()

Here's a picture which makes the result reasonable:

The theorem says that if g is caught between f and h, and if f and h both approach a limit L, then g is "squeezed" to the same limit L.

This result is sometimes called the Sandwich Theorem, the idea being that g is the filling of the sandwich and it's caught between the two slices of bread (f and h).

Proof. Let ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , I can find

, I can find

![]() so that

so that ![]() implies

implies

![]()

Since ![]() , I can find

, I can find

![]() so that

so that ![]() implies

implies

![]()

Let ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Thus, if ![]() , then

, then

![]()

Therefore,

![]()

Now ![]() means

means ![]() is less than

is less than ![]() from L, so

from L, so

![]()

And ![]() means that

means that ![]() is less than

is less than ![]() from L, so

from L, so

![]()

Hence,

![]()

Therefore,

![]()

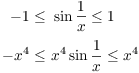

Example. Prove that ![]() .

.

Note that as ![]() the expression

the expression ![]() is undefined. So, for instance, you can't

use the rule for the limit of a product.

is undefined. So, for instance, you can't

use the rule for the limit of a product.

From trigonometry, ![]() for all

for all ![]() . So

. So

(Note that since ![]() , multiplying the inequality by

, multiplying the inequality by

![]() does not cause the inequality to "flip".)

Now

does not cause the inequality to "flip".)

Now

![]()

By the Squeezing Theorem,

![]()

The next result doesn't seem to have a standard name, so I'll call it

The Neighborhood Theorem. It says that the

value of ![]() depends on the

values of

depends on the

values of ![]() near c, not at c. I'll

often use this result in computing limits involving

indeterminate forms.

near c, not at c. I'll

often use this result in computing limits involving

indeterminate forms.

In many presentations of calculus, this result isn't stated explicitly. Instead, you'll see it used in the middle of computations like this:

![]()

Note that you can only cancel the ![]() terms if you know

terms if you know

![]() , i.e. if

, i.e. if ![]() . The author will

justify this by saying something like: "We can cancel the

. The author will

justify this by saying something like: "We can cancel the ![]() terms because in taking the limit, we only consider

x's near 1, rather than

terms because in taking the limit, we only consider

x's near 1, rather than ![]() ."

."

The Neighborhood Theorem applies to this situation in this way: the

functions ![]() and

and ![]() are equal for all x except

are equal for all x except ![]() . Therefore, the Neighborhood Theorem says that they

have the same limit as x approaches 1.

. Therefore, the Neighborhood Theorem says that they

have the same limit as x approaches 1.

Theorem. ( The Neighborhood Theorem) Suppose that:

(a) ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() for all x in the interval

for all x in the interval ![]() except possibly at c.

except possibly at c.

Then the limits ![]() and

and ![]() are either both defined or both

undefined. If they are both defined, then they have the same value.

are either both defined or both

undefined. If they are both defined, then they have the same value.

In other words, if two functions are equal in a neighborhood of c, except possibly at c, then they have the same limit at c.

Proof. Suppose that ![]() and

and ![]() for all x in the interval

for all x in the interval

![]() except possibly at c.

except possibly at c.

Suppose first that ![]() . I will show that

. I will show that ![]() .

.

Let ![]() . I must find

. I must find ![]() such that if

such that if ![]() ,

then

,

then ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , the limit

definition produces a

, the limit

definition produces a ![]() such that if

such that if ![]() , then

, then ![]() . So

take this

. So

take this ![]() , and suppose that

, and suppose that ![]() . By the choice of

. By the choice of ![]() , I get

, I get

![]()

But notice that my assumption ![]() includes the assumption that

includes the assumption that ![]() . In

particular,

. In

particular, ![]() , since if

, since if ![]() , then

, then ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , I have

, I have ![]() , so

, so

![]()

This proves that ![]() .

.

The remaining case is that ![]() is undefined. In this case, I must show that

is undefined. In this case, I must show that ![]() is undefined. Suppose not. Then

is undefined. Suppose not. Then

![]() is defined so

is defined so ![]() for some number L. But then

the first part of the proof (with the roles of

for some number L. But then

the first part of the proof (with the roles of ![]() and

and ![]() switched) shows that

switched) shows that ![]() . This contradicts my

assumption that

. This contradicts my

assumption that ![]() is

undefined.

is

undefined.

Hence, ![]() is undefined.

is undefined.![]()

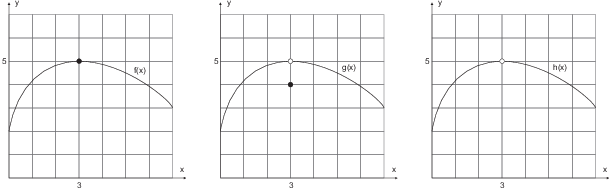

The functions ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() which are graphed below are equal for all x except

which are graphed below are equal for all x except

![]() . By the Neighborhood Theorem, the three functions

have the same limit as x approaches 3:

. By the Neighborhood Theorem, the three functions

have the same limit as x approaches 3:

![]()

Copyright 2024 by Bruce Ikenaga