The derivative of a function ![]() tells us about

the rate of change of f. If

tells us about

the rate of change of f. If ![]() is a function with 2 inputs and 1 output, what does

"rate of change" mean?

is a function with 2 inputs and 1 output, what does

"rate of change" mean?

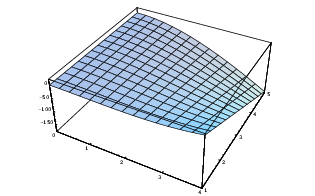

The graph of ![]() is a surface in 3 dimensions.

Imagine standing somewhere on the surface. How steep is the surface

there?

is a surface in 3 dimensions.

Imagine standing somewhere on the surface. How steep is the surface

there?

A little thought shows that the question is ambiguous. For example, if you're standing on the side of a hill, the slope is steep in the uphill and downhill directions. On the other hand, the slope is gentle if you walk along the side of the hill at a constant altitude.

You can see that in order to discuss the rate of change of a function

of several variables, you need to specify the direction in which the

change occurs. This may seem to be a complicated proposition. At a

given point ![]() , you can move in infinitely many

directions.

, you can move in infinitely many

directions.

For simplicity, suppose I'll consider changes in the x- and

y-directions first. If you're at the point ![]() and you move in the x-direction by a small amount h,

you wind up at the point

and you move in the x-direction by a small amount h,

you wind up at the point ![]() . The change in f is

. The change in f is

![]()

The average rate of change is

![]()

As usual, you can take the limit as ![]() to obtain the instantaneous rate of change:

to obtain the instantaneous rate of change:

![]()

This is the partial derivative of f with respect to

x; notice that the notation ![]() is a little

different than the

is a little

different than the ![]() notation for ordinary

derivatives. Likewise, the partial derivative of f

with respect to y is

notation for ordinary

derivatives. Likewise, the partial derivative of f

with respect to y is

![]()

It measures the rate at which f changes as y changes.

Subscripts can also be used to denote partial derivatives. Thus,

![]()

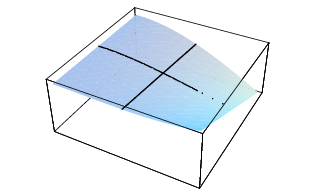

To see what partial derivatives mean pictorially, consider the graph

of a surface ![]() :

:

The partial derivatives of f at a point on the surface are the rates

of change of f in the x- and y-directions. Draw curves through the

point in the x- and y-directions. Then ![]() and

and ![]() are just the slopes of these

curves at the point.

are just the slopes of these

curves at the point.

Notice that in computing these partial derivatives, you change one variable at a time, holding the other constant. This is the key to computing partial derivatives: You differentiate as usual with respect to one variable at a time, holding the others constant.

Example. Compute the partial derivatives of

![]() .

.

The partial derivatives are

![]()

Notice that I used the product rule in computing ![]() , because f is a product (x times

, because f is a product (x times ![]() ) with respect to x. But I don't need the product

rule to compute

) with respect to x. But I don't need the product

rule to compute ![]() : with respect to y, the first

factor x is constant.

: with respect to y, the first

factor x is constant.![]()

Example. Compute the partial derivatives of

![]() .

.

![]()

Example. Suppose ![]() is a function of x alone and

is a function of x alone and ![]() is a function of y alone. Compute the partial

derivatives of

is a function of y alone. Compute the partial

derivatives of ![]() .

.

![]()

The same idea applies to computing partial derivatives of functions

of more than two variables. For example, the partial derivatives of

![]() are

are

![]()

In each case, you compute the partial derivative with respect to the variable FOO by differentiating with respect to FOO while holding the other variables constant.

Here's the general definition for a function ![]() of n variables. Assume

of n variables. Assume ![]() , where U is a subset of

, where U is a subset of ![]() . We usually assume U is an open

set, but you don't need to worry about it in this course.

. We usually assume U is an open

set, but you don't need to worry about it in this course.

Definition. The partial

derivative of f with respect to ![]() is

is

![]()

Since this is just the derivative of the single variable function

![]() , all your

usual derivative formulas from single-variable calculus work. I won't

them all, but here are some examples.

, all your

usual derivative formulas from single-variable calculus work. I won't

them all, but here are some examples.

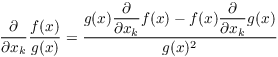

Proposition. Suppose ![]() ,

, ![]() are

functions of n variables

are

functions of n variables ![]() ,

, ![]() , ...

, ... ![]() , and c is a number.

, and c is a number.

(a) ![]() .

.

(b) ![]() .

.

(c) ![]() .

.

(d)  , provided

that

, provided

that ![]() .

.![]()

I've written ![]() for short.

for short.

Example. Compute the partial derivatives of

![]() .

.

![]()

Example. Compute the partial derivatives of

![]() .

.

![]()

There are also have higher order derivatives, and here some

complications can arise. Suppose ![]() . The second

derivatives should be the derivatives of the first derivatives. There

are two first derivatives,

. The second

derivatives should be the derivatives of the first derivatives. There

are two first derivatives, ![]() and

and ![]() , and each of these may be differentiated with

respect to x and to y. So there seem to be 4 second-order partials,

, and each of these may be differentiated with

respect to x and to y. So there seem to be 4 second-order partials,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(Notice that the subscript notation has the bottom variables in the opposite order from the fractional notation. The rationale is that in the subscript notation, variables "pile up" on the right side as you take more derivatives.)

Example. Compute the second partial

derivatives of ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

Notice that the two mixed partials ![]() and

and ![]() are equal. In fact,

this fact (which is called equality of mixed

partials is true for most "nice" functions. The

technical definition of "niceness" is that the function

are equal. In fact,

this fact (which is called equality of mixed

partials is true for most "nice" functions. The

technical definition of "niceness" is that the function

![]() have continuous second-order partial

derivatives. Here's the result stated in all its technical glory.

have continuous second-order partial

derivatives. Here's the result stated in all its technical glory.

Theorem. Suppose U is an open subset of ![]() and

and ![]() is a function of n

variables. If the second-order partial derivatives of f are

continuous, then for

is a function of n

variables. If the second-order partial derivatives of f are

continuous, then for ![]() ,

,

![]()

With appropriate assumptions, higher-order mixed partials involving the same variables to the same orders are also equal. For example, for a function of 3 variables satisfying the right assumptions,

![]()

Example. Compute the second partial

derivatives of ![]() .

.

There are 3 first-order partials, each of which has 3 partial

derivatives, so there are 9 second-order partials. But equality of

mixed partials implies that some of these will be the same; for

example, ![]() . There are actually only 6

distinct second-order partials.

. There are actually only 6

distinct second-order partials.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Copyright 2018 by Bruce Ikenaga