Definition. Let ![]() . The characteristic polynomial of A is

. The characteristic polynomial of A is

![]()

(I is the ![]() identity matrix.)

identity matrix.)

A root of the characteristic polynomial is called an eigenvalue (or a characteristic value) of A.

While the entries of A come from the field F, it makes sense to ask

for the roots of ![]() in an extension field E of F. For

example, if A is a matrix with real entries, you can ask for the

eigenvalues of A in

in an extension field E of F. For

example, if A is a matrix with real entries, you can ask for the

eigenvalues of A in ![]() or in

or in ![]() .

.

Example. Consider the matrix

![]()

The characteristic polynomial is ![]() . Hence, A has no

eigenvalues in

. Hence, A has no

eigenvalues in ![]() . Its eigenvalues in

. Its eigenvalues in ![]() are

are ![]() .

.![]()

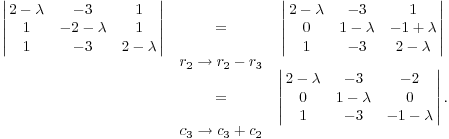

Example. Let

![$$A = \left[\matrix{2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \in M(3, \real).$$](eigenvalue12.png)

You can use row and column operations to simplify the computation of

![]() :

:

(Adding a multiple of a row or a column to a row or column, respectively, does not change the determinant.) Now expand by cofactors of the second row:

![]()

The eigenvalues are ![]() ,

, ![]() (double).

(double).![]()

Example. A matrix ![]() is upper triangular if

is upper triangular if ![]() for

for ![]() . Thus, the entries below the main

diagonal are zero. ( Lower triangular matrices

are defined in an analogous way.)

. Thus, the entries below the main

diagonal are zero. ( Lower triangular matrices

are defined in an analogous way.)

The eigenvalues of a triangular matrix

![$$A = \left[\matrix{\lambda_1 & * & \cdots & * \cr 0 & \lambda_2 & \cdots & * \cr \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \cr 0 & 0 & \cdots & \lambda_n \cr}\right]$$](eigenvalue21.png)

are just the diagonal entries ![]() . (You can prove this by induction on n.)

. (You can prove this by induction on n.)![]()

Remark. To find the eigenvalues of a matrix, you need to find the roots of the characteristic polynomial.

There are formulas for finding the roots of polynomials of degree

![]() . (For example, the quadratic formula gives the roots

of a quadratic equation

. (For example, the quadratic formula gives the roots

of a quadratic equation ![]() .) However, Abel showed

in the early part of the 19-th century that the general quintic is

not solvable by radicals. (For example,

.) However, Abel showed

in the early part of the 19-th century that the general quintic is

not solvable by radicals. (For example, ![]() is not

solvable by radicals over

is not

solvable by radicals over ![]() .) In the real

world, the computation of eigenvalues often requires numerical

approximation.

.) In the real

world, the computation of eigenvalues often requires numerical

approximation. ![]()

If ![]() is an eigenvalue of A, then

is an eigenvalue of A, then ![]() . Hence, the

. Hence, the ![]() matrix

matrix ![]() is not invertible. It follows that

is not invertible. It follows that ![]() must row reduce to a row reduced echelon matrix R

with fewer than n leading coefficients. Thus, the system

must row reduce to a row reduced echelon matrix R

with fewer than n leading coefficients. Thus, the system ![]() has at least one free variable, and hence has more

than one solution. In particular,

has at least one free variable, and hence has more

than one solution. In particular, ![]() --- and therefore,

--- and therefore,

![]() --- has at least one nonzero

solution.

--- has at least one nonzero

solution.

Definition. Let ![]() , and let

, and let

![]() be an eigenvalue of A. An

eigenvector (or a characteristic vector)

of A for

be an eigenvalue of A. An

eigenvector (or a characteristic vector)

of A for ![]() is a nonzero vector

is a nonzero vector ![]() such that

such that

![]()

Equivalently,

![]()

Example. Let

![$$A = \left[\matrix{2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \in M(3, \real).$$](eigenvalue41.png)

The eigenvalues are ![]() ,

, ![]() (double).

(double).

First, I'll find an eigenvector for ![]() .

.

![$$A - 0\cdot I = \left[\matrix{2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue45.png)

I want ![]() such that

such that

![$$\left[\matrix{2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{a \cr b \cr c \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{0 \cr 0 \cr 0 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue47.png)

You can solve the system by row reduction. Since the column of zeros

on the right will never change, it's enough to row reduce the ![]() matrix on the right.

matrix on the right.

![$$\left[\matrix{2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \quad \to \quad \left[\matrix{1 & 0 & -1 \cr 0 & 1 & -1 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr}\right]$$](eigenvalue49.png)

This says

![]()

Therefore, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the eigenvector is

, and the eigenvector is

![$$\left[\matrix{a \cr b \cr c \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{c \cr c \cr c \cr}\right] = c \left[\matrix{1 \cr 1 \cr 1 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue53.png)

Notice that this is the usual algorithm for finding a basis for the solution space of a homogeneous system (or the null space of a matrix).

I can set c to any nonzero number. For example, ![]() gives the eigenvector

gives the eigenvector ![]() . Notice that

there are infinitely many eigenvectors for this eigenvalue, but all

of these eigenvectors are multiples of

. Notice that

there are infinitely many eigenvectors for this eigenvalue, but all

of these eigenvectors are multiples of ![]() .

.

Likewise,

![$$A - I = \left[\matrix{1 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 1 \cr}\right] \quad \to \quad \left[\matrix{1 & -3 & 1 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr}\right]$$](eigenvalue57.png)

Hence, the eigenvectors are

![$$\left[\matrix{a \cr b \cr c \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{3b - c \cr b \cr c \cr}\right] = b \left[\matrix{3 \cr 1 \cr 0 \cr}\right] + c \left[\matrix{-1 \cr 0 \cr 1 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue58.png)

Taking ![]() ,

, ![]() gives

gives ![]() ; taking

; taking ![]() ,

, ![]() gives

gives ![]() . This

eigenvalue gives rise to two independent eigenvectors.

. This

eigenvalue gives rise to two independent eigenvectors.

Note, however, that a double root of the characteristic polynomial

need not give rise to two independent eigenvectors.![]()

Definition. Matrices ![]() are similar if there is an

invertible matrix

are similar if there is an

invertible matrix ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

.

Lemma. Similar matrices have the same characteristic polynomial (and hence the same eigenvalues).

Proof.

![]()

Therefore, the matrices ![]() and

and ![]() are similar. Hence, they have the same

determinant. The determinant of

are similar. Hence, they have the same

determinant. The determinant of ![]() is the characteristic

polynomial of A and the determinant of

is the characteristic

polynomial of A and the determinant of ![]() is

the characteristic polynomial of

is

the characteristic polynomial of ![]() .

.![]()

Definition. Let ![]() be a

linear transformation, where V is a finite-dimensional vector space.

The characteristic polynomial of T is the

characteristic polynomial of a matrix of T relative to a basis

be a

linear transformation, where V is a finite-dimensional vector space.

The characteristic polynomial of T is the

characteristic polynomial of a matrix of T relative to a basis ![]() of V.

of V.

The preceding lemma shows that this is independent of the choice of

basis. For if ![]() and

and ![]() are bases for V, then

are bases for V, then

![]()

Therefore, ![]() and

and ![]() are similar, so they have the same

characteristic polynomial.

are similar, so they have the same

characteristic polynomial.

This shows that it makes sense to speak of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a linear transformation T.

Definition. A matrix ![]() is diagonalizable if A has n

independent eigenvectors --- that is, if there is a basis for

is diagonalizable if A has n

independent eigenvectors --- that is, if there is a basis for ![]() consisting of eigenvectors of A.

consisting of eigenvectors of A.

Proposition. ![]() is

diagonalizable if and only if it is similar to a diagonal matrix.

is

diagonalizable if and only if it is similar to a diagonal matrix.

Proof. Let ![]() be n

independent eigenvectors for A corresponding to eigenvalues

be n

independent eigenvectors for A corresponding to eigenvalues ![]() . Let T be the linear

transformation corresponding to A:

. Let T be the linear

transformation corresponding to A:

![]()

Since ![]() for all i, the matrix of T

relative to the basis

for all i, the matrix of T

relative to the basis ![]() is

is

![$$[T]_{{\cal B}, {\cal B}} = \left[\matrix{\lambda_1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \cr 0 & \lambda_2 & \cdots & 0 \cr \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \cr 0 & 0 & \cdots & \lambda_n \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue89.png)

Now A is the matrix of T relative to the standard basis, so

![]()

The matrix ![]() is obtained by building a

matrix using the

is obtained by building a

matrix using the ![]() as the columns. Then

as the columns. Then ![]() .

.

Hence,

![$$\left[\matrix{\lambda_1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \cr 0 & \lambda_2 & \cdots & 0 \cr \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \cr 0 & 0 & \cdots & \lambda_n \cr}\right] = [{\cal B} \to {\rm std}]^{-1}\cdot A \cdot [{\cal B} \to {\rm std}].$$](eigenvalue94.png)

Conversely, if D is diagonal, P is invertible, and ![]() , the columns

, the columns ![]() of P are independent

eigenvectors for A. In fact, if

of P are independent

eigenvectors for A. In fact, if

![$$D = \left[\matrix{\lambda_1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \cr 0 & \lambda_2 & \cdots & 0 \cr \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \cr 0 & 0 & \cdots & \lambda_n \cr}\right],$$](eigenvalue97.png)

then ![]() says

says

![$$\left[\matrix{\uparrow & \uparrow & & \uparrow \cr c_1 & c_2 & \cdots & c_n \cr \downarrow & \downarrow & & \downarrow \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{\lambda_1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \cr 0 & \lambda_2 & \cdots & 0 \cr \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \cr 0 & 0 & \cdots & \lambda_n \cr}\right] = A \left[\matrix{\uparrow & \uparrow & & \uparrow \cr c_1 & c_2 & \cdots & c_n \cr \downarrow & \downarrow & & \downarrow \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue99.png)

Hence, ![]() .

.![]()

Example. Consider the matrix matrix

![$$A = \left[\matrix{2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \in M(3, \real).$$](eigenvalue101.png)

In an earlier example, I showed that A has 3 independent eigenvectors

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() . Therefore, A

is diagonalizable.

. Therefore, A

is diagonalizable.

To find a diagonalizing matrix, build a matrix using the eigenvectors as the columns:

![$$P = \left[\matrix{ 1 & 3 & 1 \cr 1 & 1 & 0 \cr 1 & 0 & 1 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue105.png)

You can check by finding ![]() and doing the multiplication that

you get a diagonal matrix:

and doing the multiplication that

you get a diagonal matrix:

![$$P^{-1} A P = \left[\matrix{ 1 & 3 & 1 \cr 1 & 1 & 0 \cr 1 & 0 & 1 \cr}\right]^{-1} \left[\matrix{ 2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{ 1 & 3 & 1 \cr 1 & 1 & 0 \cr 1 & 0 & 1 \cr}\right] =$$](eigenvalue107.png)

![$$\left[\matrix{ -1 & 3 & -1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{ 2 & -3 & 1 \cr 1 & -2 & 1 \cr 1 & -3 & 2 \cr}\right] \left[\matrix{ 1 & 3 & 1 \cr 1 & 1 & 0 \cr 1 & 0 & 1 \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{ 0 & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & 1 & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 1 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue108.png)

Of course, I knew this was the answer! I should get a diagonal matrix with the eigenvalues on the main diagonal, in the same order that I put the corresponding eigenvectors into P.

You can put the eigenvectors in as the columns of P in any order: A

different order will give a diagonal matrix with the eigenvalues on

the main diagonal in a different order.![]()

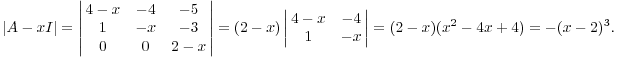

Example. Let

![$$A = \left[\matrix{ 4 & -4 & -5 \cr 1 & 0 & -3 \cr 0 & 0 & 2 \cr}\right] \in M(3, \real).$$](eigenvalue109.png)

Find the eigenvalues and, for each eigenvalue, a complete set of

eigenvectors. If A is diagonalizable, find a matrix P such that ![]() is a diagonal matrix.

is a diagonal matrix.

The eigenvalue is ![]() .

.

Now

![$$A - 2I = \left[\matrix{ 2 & -4 & -5 \cr 1 & -2 & -3 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr}\right] \to \left[\matrix{ 1 & -2 & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 1 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue113.png)

Thinking of this as the coefficient matrix of a homogeneous linear system with variables a, b, and c, I obtain the equations

![]()

Then ![]() , so

, so

![$$\left[\matrix{a \cr b \cr c \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{2b \cr b \cr 0 \cr}\right] = b\cdot \left[\matrix{2 \cr 1 \cr 0 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue116.png)

![]() is an eigenvector. Since there's only one independent

eigenvector --- as opposed to 3 --- the matrix A is not

diagonalizable.

is an eigenvector. Since there's only one independent

eigenvector --- as opposed to 3 --- the matrix A is not

diagonalizable.![]()

Example. The following matrixhas eigenvalue

![]() (a triple root):

(a triple root):

![$$B = \left[\matrix{-3 & 3 & -5 \cr 12 & -7 & 14 \cr 10 & -7 & 13 \cr}\right] \in M(3, \real).$$](eigenvalue119.png)

Now

![$$B - 1\cdot I = \left[\matrix{ -4 & 3 & -5 \cr 12 & -8 & 14 \cr 10 & -7 & 12 \cr}\right] \to \left[\matrix{ 1 & 0 & \dfrac{1}{2} \cr 0 & 1 & -1 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr}\right]$$](eigenvalue120.png)

Thinking of this as the coefficient matrix of a homogeneous linear system with variables a, b, and c, I obtain the equations

![]()

Set ![]() . This gives

. This gives ![]() and

and ![]() . Thus, the only eigenvectors are the nonzero

multiples of

. Thus, the only eigenvectors are the nonzero

multiples of ![]() . Since there is only one independent

eigenvectors, B is not diagonalizable.

. Since there is only one independent

eigenvectors, B is not diagonalizable.![]()

Proposition. Let ![]() be a linear transformation on an n dimensional vector

space. If

be a linear transformation on an n dimensional vector

space. If ![]() are eigenvectors corresponding to

the distinct eigenvalues

are eigenvectors corresponding to

the distinct eigenvalues ![]() , then

, then ![]() is independent.

is independent.

Proof. Suppose to the contrary that ![]() is dependent. Let p be the smallest number

such that the subset

is dependent. Let p be the smallest number

such that the subset ![]() is dependent. Then

there is a nontrivial linear relation

is dependent. Then

there is a nontrivial linear relation

![]()

Note that ![]() , else

, else

![]()

This would contradict minimality of p.

Hence, I can rewrite the equation above in the form

![]()

Apply T to both sides, and use ![]() :

:

![]()

On the other hand,

![]()

Subtract the last equation from the one before it to obtain

![]()

Since the eigenvalues are distinct, the terms ![]() are nonzero. Hence, this is a linear

relation in

are nonzero. Hence, this is a linear

relation in ![]() which contradicts minimality of p

--- unless

which contradicts minimality of p

--- unless ![]() .

.

In this case, ![]() , which contradicts the fact that

, which contradicts the fact that ![]() is an eigenvector. Therefore, the original set must

in fact be independent.

is an eigenvector. Therefore, the original set must

in fact be independent. ![]()

Example. Let A be an ![]() real matrix. The complex eigenvalues of A

always come in conjugate pairs

real matrix. The complex eigenvalues of A

always come in conjugate pairs ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Moreover, if v is an eigenvector for ![]() , then

the conjugate

, then

the conjugate ![]() is an eigenvector for

is an eigenvector for ![]() .

.

For suppose ![]() . Taking complex conjugates, I get

. Taking complex conjugates, I get

![]()

(![]() because A is a real matrix.)

because A is a real matrix.)

In practical terms, this means that once you've found an eigenvector for one complex eigenvalue, you can get an eigenvector for the conjugate eigenvalue by taking the conjugate of the eigenvector. You don't need to do a separate eigenvector computation.

For example, suppose

![]()

The characteristic polynomial is ![]() .

The eigenvalues are

.

The eigenvalues are ![]() .

.

Find an eigenvector for ![]() :

:

![]()

I knew that the second row ![]() must be a multiple of the

first row, because I know the system has nontrivial solutions. So I

don't have to work out what multiple it is; I can just zero

out the second row on general principles.

must be a multiple of the

first row, because I know the system has nontrivial solutions. So I

don't have to work out what multiple it is; I can just zero

out the second row on general principles.

This only works for ![]() matrices, and only for

those which are

matrices, and only for

those which are ![]() 's in eigenvector computations.

's in eigenvector computations.

Next, there's no point in going all the way to row reduced echelon

form. I just need some nonzero vector ![]() such that

such that

![]()

That is, I want

![]()

I can find an a and b that work by swapping ![]() and -1, and negating one of them. For example, take

and -1, and negating one of them. For example, take

![]() (-1 negated) and

(-1 negated) and ![]() . This checks:

. This checks:

![]()

So ![]() is an eigenvector for

is an eigenvector for ![]() .

.

By the discussion at the start of the example, I don't need to do a

computation for ![]() . Just conjugate the previous

eigenvector:

. Just conjugate the previous

eigenvector: ![]() must be an eigenvector for

must be an eigenvector for ![]() .

.

Since there are 2 independent eigenvectors, you can use them construct a diagonalizing matrix for A:

![]()

Notice that you get a diagonal matrix with the eigenvalues on the

main diagonal, in the same order in which you listed the

eigenvectors.![]()

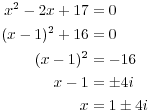

Example. For the following matrix, find the

eigenvalues over ![]() , and for each eigenvalue, a

complete set of independent eigenvectors.

, and for each eigenvalue, a

complete set of independent eigenvectors.

Find a diagonalizing matrix and the corresponding diagonal matrix.

![$$A = \left[\matrix{ -2 & 0 & 5 \cr 0 & 2 & 0 \cr -5 & 0 & 4 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue176.png)

The characteristic polynomial is

![$$|A - x I| = \left|\matrix{ -2 - x & 0 & 5 \cr 0 & 2 - x & 0 \cr -5 & 0 & 4 - x \cr}\right| = (2 - x) \left|\matrix{ -2 - x & 5 \cr -5 & 4 - x \cr}\right| = (2 - x)[(x + 2)(x - 4) + 25] =$$](eigenvalue177.png)

![]()

Now

The eigenvalues are ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

For ![]() , I have

, I have

![$$A - 2 I = \left[\matrix{ -4 & 0 & 5 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr -5 & 0 & 2 \cr}\right] \quad \to \quad \left[\matrix{ 1 & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 1 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue183.png)

With variables a, b, and c, the corresponding homogeneous system is

![]() and

and ![]() . This gives the solution vector

. This gives the solution vector

![$$\left[\matrix{a \cr b \cr c \cr}\right] = \left[\matrix{0 \cr b \cr 0 \cr}\right] = b \cdot \left[\matrix{0 \cr 1 \cr 0 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue186.png)

Taking ![]() , I obtain the eigenvector

, I obtain the eigenvector ![]() .

.

For ![]() , I have

, I have

![$$\left[\matrix{ -3 - 4 i & 0 & 5 \cr 0 & 1 - 4 i & 0 \cr -5 & 0 & 3 - 4 i \cr}\right] \quad \to \quad \left[\matrix{ -5 & 0 & 3 - 4 i \cr 0 & 1 & 0 \cr -5 & 0 & 3 - 4 i \cr}\right]$$](eigenvalue190.png)

I multiplied the first row by ![]() , then divided it by 5. This

made it the same as the third row.

, then divided it by 5. This

made it the same as the third row.

I divided the second row by ![]() .

.

(I knew the the first and third rows had to be multiples, since they're clearly independent of the second row. Thus, if they weren't multiples, the three rows would be independent, the eigenvector matrix would be invertible, and there would be no eigenvectors [which must be nonzero].)

Now I can wipe out the third row by subtracting the first:

![$$\left[\matrix{ -5 & 0 & 3 - 4 i \cr 0 & 1 & 0 \cr -5 & 0 & 3 - 4 i \cr}\right] \quad \to \quad \left[\matrix{ -5 & 0 & 3 - 4 i \cr 0 & 1 & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue193.png)

With variables a, b, and c, the corresponding homogeneous system is

![]()

There will only be one parameter (c), so there will only be one

independent eigenvector. To get one, switch the "-5" and

"![]() " and negate the "-5" to get

"5". This gives

" and negate the "-5" to get

"5". This gives ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . You can see that these values

for a and c work:

. You can see that these values

for a and c work:

![]()

Thus, my eigenvector is ![]() .

.

Hence, an eigenvector for ![]() is the conjugate

is the conjugate ![]() .

.

A diagonalizing matrix is given by

![$$P = \left[\matrix{ 0 & 3 - 4 i & 3 + 4 i \cr 1 & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & 5 & 5 \cr}\right].$$](eigenvalue203.png)

With this diagonalizing matrix, I have

![$$P^{-1} A P = \left[\matrix{ 2 & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & 1 + 4 i & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 1 - 4 i \cr}\right].\quad\halmos$$](eigenvalue204.png)

Copyright 2011 by Bruce Ikenaga