In this section, I'll collect some results and terminology connected with functions. I'll assume that you have some experience with functions from earlier courses, and I won't give a formal definition of "function".

If X and Y are sets, the notation ![]() denotes a function named

"f" which takes its inputs from the sets X and produces

outputs in the set Y. The set X is callled the

domain and the set Y is called the

codomain.

denotes a function named

"f" which takes its inputs from the sets X and produces

outputs in the set Y. The set X is callled the

domain and the set Y is called the

codomain.

What I just described is notation for functions; I'm not

giving a precise definition of what a function is. You've

seen functions in other courses --- calculus, for instance. You were

probably told at some point that a function is a "rule" for

producing outputs from inputs, and this intuitive idea is okay for

this course. However, if you're someone who likes causing trouble for

yourself, you can do so here by asking what a "rule" is:

It's not so easy to say in a precise way. I'll give a quick

description of the solution, and let you read more in a book on set

theory or math proof if you're interested. A function from a set X to

a set Y is a subset of the product ![]() , such that if

, such that if ![]() and

and ![]() are in the subset, then

are in the subset, then ![]() . For this course, you do not need to understand the

last sentence!

. For this course, you do not need to understand the

last sentence!

The sets X and Y are part of the definition of the function. In some

elementary courses, all the functions take real numbers (or at least

some real numbers) to real numbers, and the domain and codomain are

"understood". The "domain" (or

natural domain, as it is sometimes called) is the largest set of

real numbers for which the expression defining the function is

defined. In such a course, for example, the "domain" of

![]() would be all real numbers except for 1.

would be all real numbers except for 1.

In this course, however, we'll be careful and specify the domain and codomain explicitly. This becomes important, for instance, in defining injective and surjective functions.

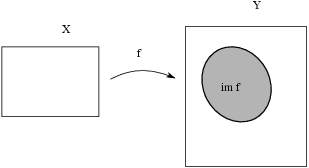

If ![]() is a function, the image of f

(denoted

is a function, the image of f

(denoted ![]() ) is the set of all possible outputs of f. In terms

of set notation,

) is the set of all possible outputs of f. In terms

of set notation,

![]()

Notice that the image of f is contained in the codomain Y, but it can be smaller than Y.

You might have heard the term range used in connection with functions, but we'll avoid it because it was (unfortunately) used in two different ways. Sometimes, it meant what I've called the codomain, but it was also used to refer to what is now called the image. The codomain is simply a set which contains all possible outputs of the function (the image), but not every element of the codomain must be an output of the function.

Remark. (a) When you write the definition of a

function like "![]() ", you can use whatever

variable you wish for the input. It would be the same to write

"

", you can use whatever

variable you wish for the input. It would be the same to write

"![]() ". You could use a word for the input

to the function (as is often done in compute programming) and write

". You could use a word for the input

to the function (as is often done in compute programming) and write

![]()

You could even use words for the whole definition: "The function f is defined by taking an input, squaring it, and adding 1, and returning the result as the output." This is the way math was written before people started using symbols --- and you can see why people started using symbols!

In math, unlike in computer programming, it has been traditional to save writing and use single letters to name variables, such as the variables used to define functions. There are also some loose conventions about what letters you use for various purposes. For instance, x is often used as the input variable in a function definition, and i, j, and k are often used as index variables in summations.

(b) The variables used to define a function are only

"active" within the function definition. Once you reach the

end of the expression "![]() ", there is no

variable named "x" hanging around --- you can't ask at that

point "Is x equal to 3?" In computer programming terms, you

might say that x isn't a global variable; it's in

scope only within the definition "

", there is no

variable named "x" hanging around --- you can't ask at that

point "Is x equal to 3?" In computer programming terms, you

might say that x isn't a global variable; it's in

scope only within the definition "![]() ".

".

You might think about the last paragraph if you start getting

confused when we discuss composites and inverse functions below.![]()

Here are three key properties that a function may have.

Definition. Let ![]() be a function

with domain X and codomain Y.

be a function

with domain X and codomain Y.

(a) f is injective if ![]() implies

implies ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

(b) f is surjective if for all ![]() , there is an

, there is an ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

.

(c) f is bijective if it is injective and surjective.

The older terms (which some people still use) are one-to-one instead of injective, onto instead of surjective, and one-to-one correspondence for bijective.

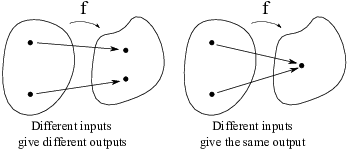

Remark. You can restate the definition of injective this way: f is

injective if ![]() implies

implies ![]() for

for ![]() . (This is the contrapositive

of the original definition.) In this form, the definition says that

different inputs always give different outputs.

. (This is the contrapositive

of the original definition.) In this form, the definition says that

different inputs always give different outputs.

If different inputs can give the same output, the function is not injective.

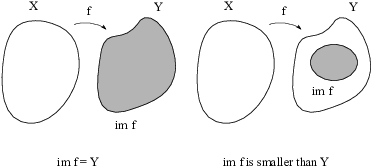

The definition of surjective means that everything in the codomain is

an output of f --- that is, ![]() .

.

If ![]() is smaller than y, so some points in Y aren't in

is smaller than y, so some points in Y aren't in ![]() , the function is not surjective.

, the function is not surjective.

To say that f is bijective means that f "pairs up" the elements of X and the elements of Y --- one element of X paired with exactly one element of Y.

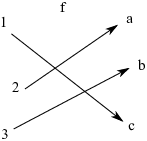

This picture shows a bijection f from the set ![]() to the set

to the set ![]() .

.

It is defined by

![]()

It is injective because two different inputs always produce two

different outputs. It is surjective because every element of the

codomain ![]() is an output of f.

is an output of f.

Example. (a) ![]() is

defined by

is

defined by ![]() . Prove that f is injective but not

surjective.

. Prove that f is injective but not

surjective.

(b) ![]() is defined by

is defined by

![]()

Prove that f is surjective but not injective.

(c) ![]() is defined by

is defined by ![]() . Prove

that f is bijective.

. Prove

that f is bijective.

(a) Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , so

, so ![]() , and hence

, and hence ![]() . Thus, f is injective.

. Thus, f is injective.

f is not surjective, because there is no ![]() such that

such that ![]() . This would imply

. This would imply ![]() , but

, but ![]() is positive for all x.

is positive for all x.![]()

(b) Let ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . In both cases, I've found an

input to f which produces the output y. So f is surjective.

. In both cases, I've found an

input to f which produces the output y. So f is surjective.

f is not injective: ![]() , and

, and ![]() , so

, so ![]() but

but ![]() .

.

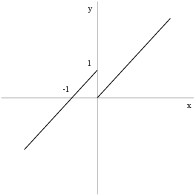

The graph of f is shown below.

In the case of functions ![]() , you can interpret

surjectivity this way: Every horizontal line hits the graph at least

once. You can interpret injectivity this way: No horizontal line hits

the graph more than once. Look at the graph and see how it shows that

f is surjective, but not injective.

, you can interpret

surjectivity this way: Every horizontal line hits the graph at least

once. You can interpret injectivity this way: No horizontal line hits

the graph more than once. Look at the graph and see how it shows that

f is surjective, but not injective.

While this is visually appealing, this is a special case ---

do not remember these ideas as the definitions of injective

and surjective. For instance, they would not apply if you had a

function ![]() .

.

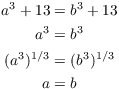

(c) Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

Hence, f is injective.

Suppose ![]() . I need

. I need ![]() such that

such that ![]() . I will work backwards to "guess" what x

should be, then verify my guess.

. I will work backwards to "guess" what x

should be, then verify my guess.

![]() means

means ![]() , so

, so ![]() , and

, and ![]() . That's my "guess" for x; I still have to

show it works. (Why doesn't what I did prove it? Because I worked

backwards, so I have to check that all the steps I took are

reversible.) Here's the check:

. That's my "guess" for x; I still have to

show it works. (Why doesn't what I did prove it? Because I worked

backwards, so I have to check that all the steps I took are

reversible.) Here's the check:

![]()

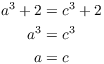

Hence, f is surjective. Since f is injective and surjective, it's

bijective.![]()

Example. ![]() is defined

by

is defined

by

![]()

Show that f is injective, but not surjective.

To show f is injective, suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Equating the first components, I have

Equating the second components and using ![]() , I have

, I have

Hence, ![]() , so f is injective.

, so f is injective.

To show f is not surjective, I must find a pair in ![]() which is not an output of f. There are lots of pairs

which work; I will use

which is not an output of f. There are lots of pairs

which work; I will use ![]() . So suppose

. So suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Equating the first components, I have

Equating the second components and using ![]() , I have

, I have

This is a contradiction, since ![]() for all y. So there is no

input

for all y. So there is no

input ![]() such that

such that ![]() , and hence f is not

surjective.

, and hence f is not

surjective.

The thought process I used in choosing ![]() was this. I saw

that the expression

was this. I saw

that the expression ![]() was restricted in the values it can take:

It's always positive. So I tried to get a contradiction by forcing it

to equal a negative number. I could do this by forcing x in

was restricted in the values it can take:

It's always positive. So I tried to get a contradiction by forcing it

to equal a negative number. I could do this by forcing x in ![]() to be positive. I could force

to be positive. I could force ![]() by setting the first component

by setting the first component ![]() to a value so that solving for x would produce a

positive number --- 10 happens to work.

to a value so that solving for x would produce a

positive number --- 10 happens to work.![]()

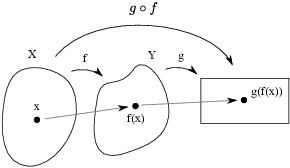

Definition. Let X, Y, and Z be sets, and let

![]() and

and ![]() be functions. The composite of f and g is the function

be functions. The composite of f and g is the function ![]() defined by

defined by

![]()

Note that "![]() " does not mean

multiplication. I will often write "

" does not mean

multiplication. I will often write "![]() " for the

composite, to ensure that there's no confusion. Also, "

" for the

composite, to ensure that there's no confusion. Also, "![]() " is read from right to left, so it means

"do f first, then g".

" is read from right to left, so it means

"do f first, then g".

Example. (a) Suppose ![]() is defined by

is defined by ![]() and

and ![]() is defined by

is defined by ![]() . Find

. Find ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

(b) Suppose ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() and

and ![]() is given by

is given by

![]() . Find

. Find ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

(c) Suppose ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() and

and ![]() . Find

. Find ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

(a)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Note that ![]() .

.![]()

(b)

![]()

![]()

(c)

![]()

![]()

For example, to compute ![]() , I substituted

, I substituted ![]() for s and

for s and ![]() for t in the definition of

for t in the definition of ![]() .

.![]()

Definition. Let A and B be sets, and let ![]() and

and ![]() be functions. f and g are inverses if

be functions. f and g are inverses if

![]()

The inverse of f is denoted ![]() . (Note that

"

. (Note that

"![]() " is not a "-1 power", in the sense of

a reciprocal.) Using this notation, I can write the equations in the

inverse definition as

" is not a "-1 power", in the sense of

a reciprocal.) Using this notation, I can write the equations in the

inverse definition as

![]()

The identity function on a set X is the

function ![]() defined by

defined by ![]() for all

for all ![]() . We may write "

. We may write "![]() " instead of

"

" instead of

"![]() " if it's clear what set is intended.

" if it's clear what set is intended.

Using this definition and the notation for the composite of functions, we can write the two equations which say that f and g are inverses as

![]()

Example. Define ![]() by

by ![]() and

and ![]() by

by ![]() . Show that f and g are inverses.

. Show that f and g are inverses.

Let ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

Since ![]() and

and ![]() for all

for all ![]() , it follows that f and g are inverses.

, it follows that f and g are inverses.![]()

Example. Let ![]() be

given by

be

given by ![]() . Find

. Find ![]() and verify that it's the inverse by checking the

inverse definition.

and verify that it's the inverse by checking the

inverse definition.

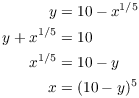

I guess ![]() by working backwards. Suppose

by working backwards. Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Solve the last equation for x:

Thus, my guess is ![]() . I got this by

assuming

. I got this by

assuming ![]() . I need to verify that my guess

works by checking the inverse definition.

. I need to verify that my guess

works by checking the inverse definition.

![]()

![]()

Since ![]() for all

for all ![]() and

and ![]() for all

for all ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() is the inverse function of f.

is the inverse function of f.![]()

Note: While I needed to use different letters x and y for the output

and input variables for ![]() , you can use any variable you

want in writing the definition of a function. So once I have my guess

for

, you can use any variable you

want in writing the definition of a function. So once I have my guess

for ![]() , I could have written the definition as

, I could have written the definition as ![]() and checked the inverse definition using

that.

and checked the inverse definition using

that.

Not every function has an inverse --- in fact, we'll see below that having an inverse is equivalent to being bijective.

Example. Define ![]() by

by ![]() . Prove that f does not have an inverse.

. Prove that f does not have an inverse.

If you have some experience with proof writing, you may know that a negative statement ("does not have an inverse") is often proved by contradiction: You assume the negation of the statement to be proved and try to get a contradiction. If the statement to be proved is a negative statement, its negation will be a positive statement.

So suppose that f has an inverse ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() for all x. In particular,

for all x. In particular, ![]() and

and ![]() . But

. But ![]() and

and ![]() , so I get

, so I get

![]()

This is a contradiction, because ![]() is a function, so

it can't produce two different outputs (2 and -2) for the same input

(14). Hence, f does not have an inverse.

is a function, so

it can't produce two different outputs (2 and -2) for the same input

(14). Hence, f does not have an inverse.![]()

Note: Instead of 2 and -2, you could choose 5 and -5 or 17 and -17,

and so on. Lots of pairs of numbers would work. You could also get a

contradiction using the equation ![]() : Take

: Take

![]() and see what happens!

and see what happens!

Example. Let ![]() be

given by

be

given by ![]() . Find

. Find ![]() and verify that it's the inverse by checking the

inverse definition.

and verify that it's the inverse by checking the

inverse definition.

I'll guess ![]() by working backwards, then verify that my

guess works. Suppose

by working backwards, then verify that my

guess works. Suppose ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

The second equality gives two equations:

![]()

The first equation gives ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Plugging this into the second equation gives

. Plugging this into the second equation gives

![]()

Thus, my guess is

![]()

I check the inverse definition:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The inverse definition checks, so ![]() .

.![]()

Note: While the names of the input variables to a function are

arbitrary, I used a and b as the input variables to ![]() rather than x and y to avoid confusion --- I was

already using x and y as the input variables for f.

rather than x and y to avoid confusion --- I was

already using x and y as the input variables for f.

The next result says that having an inverse is the same as being bijective.

Theorem. Let X and Y be sets, and let ![]() be a function. f is bijective if and only if it has

an inverse --- that is,

be a function. f is bijective if and only if it has

an inverse --- that is, ![]() exists.

exists.

Proof. To prove a statement of the form A if and only if B, I must do two things: First, I assume that A is true and prove that B is true; next, I assume that B is true and prove that A is true.

First, suppose that ![]() exists, so

exists, so

![]()

I need to prove that f is bijective.

To show that f is injective, suppose that ![]() for

for ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Therefore, f is injective.

To show f is surjective, suppose ![]() . I must find an element

of X which f maps to y. This is easy, since

. I must find an element

of X which f maps to y. This is easy, since ![]() , and

, and

![]()

Therefore, f is surjective. Hence, f is bijective.

Next, suppose f is bijective. I must show that ![]() exists. Now

exists. Now ![]() should be a

function from Y to X, so I need to start with

should be a

function from Y to X, so I need to start with ![]() and define where

and define where ![]() maps it. Since f is

bijective, it is surjective. Therefore,

maps it. Since f is

bijective, it is surjective. Therefore, ![]() for some

for some ![]() . I'd like to define

. I'd like to define ![]() .

.

There's a possible problem. In general, it's possible that ![]() and

and ![]() for

for ![]() . In that

case, how would I define

. In that

case, how would I define ![]() ?

?

Fortunately, f is injective. So if ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() , and so

, and so ![]() by injectivity. In other words, there is one and only

one

by injectivity. In other words, there is one and only

one ![]() such that

such that ![]() , and it's safe for me to

define

, and it's safe for me to

define ![]() .

.

(Notice how I used both parts of the definition of bijective ---

surjectivity and injectivity --- to define ![]() .)

.)

All I have to do is to check the inverse definition. First, if ![]() , then by definition

, then by definition ![]() is the

element of X which f takes to

is the

element of X which f takes to ![]() --- but that element

is x. Hence,

--- but that element

is x. Hence, ![]() .

.

Next, if ![]() , then by definition

, then by definition ![]() is the element

is the element ![]() such that

such that ![]() . So

. So

![]()

Thus, the function ![]() I've defined really is the inverse

of f.

I've defined really is the inverse

of f.![]()

Thus, to show a function is bijective, you just need to show the function has an inverse. Often this is easy, because you can tell what the inverse should be given the function's definition. All you have to do is check that the "obvious" inverse really is the inverse.

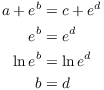

For instance, if ![]() is defined by

is defined by ![]() , it's obvious that the opposite of

"cubing" is "cube rooting". So I expect the

inverse to be

, it's obvious that the opposite of

"cubing" is "cube rooting". So I expect the

inverse to be ![]() . The check is easy:

. The check is easy:

![]()

Since f has an inverse, it's bijective.

Copyright 2022 by Bruce Ikenaga