The Chinese Remainder Theorem says that

certain systems of simultaneous congruences with different

moduli have solutions. The idea embodied in the theorem was

known to the Chinese mathematician Sunzi in the ![]() century A.D. --- hence the name.

century A.D. --- hence the name.

I'll begin by collecting some useful lemmas.

Lemma 1. Let m and ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() be positive integers.

If m is relatively prime to each of

be positive integers.

If m is relatively prime to each of ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() , then it is

relatively prime to their product

, then it is

relatively prime to their product ![]() .

.

Proof. If ![]() , then there is a prime p

which divides both m and

, then there is a prime p

which divides both m and ![]() . Now

. Now ![]() , so p must divide

, so p must divide ![]() for some i. But p divides both m and

for some i. But p divides both m and ![]() , so

, so ![]() . This

contradiction implies that

. This

contradiction implies that ![]() .

.![]()

For example, 6 is relatively prime to 25, to 7, and to 11. Now ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

I showed earlier that the greatest common divisor ![]() of a and b is greatest in the

sense that it is divisible by any common divisor of a and b. The next

result is the analogous statement for least common multiples.

of a and b is greatest in the

sense that it is divisible by any common divisor of a and b. The next

result is the analogous statement for least common multiples.

Lemma 2. Let m and ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() be positive integers.

If m is a multiple of each of

be positive integers.

If m is a multiple of each of ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() , then m is a multiple

of

, then m is a multiple

of ![]() .

.

Proof. By the Division Algorithm, there are unique numbers q and r such that

![]()

Now ![]() divides both m and

divides both m and ![]() , so

, so ![]() divides r. Since this is true for all i, r is a

common multiple of the

divides r. Since this is true for all i, r is a

common multiple of the ![]() smaller than the

least common multiple

smaller than the

least common multiple ![]() . This is only possible if

. This is only possible if ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , i.e. m is a multiple of

, i.e. m is a multiple of

![]() .

.![]()

For instance, 88 is a multiple of 4 and 22. The least common multiple of 4 and 22 is 44, and 88 is also a multiple of 44.

Lemma 3. Let ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() be positive integers.

If

be positive integers.

If ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() are pairwise relatively prime (that is,

are pairwise relatively prime (that is, ![]() for

for ![]() ), then

), then

![]()

Proof. Induct on n. The statement is trivially

true for ![]() , so I'll start with

, so I'll start with ![]() . The statement for

. The statement for ![]() follows from the equation

follows from the equation ![]() :

:

![]()

Now assume ![]() , and assume the result is true

for n. I will prove that it holds for

, and assume the result is true

for n. I will prove that it holds for ![]() .

.

Claim: ![]() .

.

(Some people take this as an iterative definition of ![]() .)

.) ![]() is a multiple of each

of

is a multiple of each

of ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() , so by Lemma 2 it's a multiple of

, so by Lemma 2 it's a multiple of ![]() . It's also a multiple of

. It's also a multiple of ![]() , so

, so

![]()

On the other hand, for ![]() ,

,

![]()

Therefore,

![]()

Obviously,

![]()

Thus, ![]() is

a common multiple of all the

is

a common multiple of all the ![]() 's. Since

's. Since ![]() is the least common multiple, Lemma 2 implies that

is the least common multiple, Lemma 2 implies that

![]()

Since I have two positive numbers which divide one another, they're equal:

![]()

This proves the claim.

Returning to the proof of the induction step, I have

![]()

The second equality follows by the induction hypothesis (the

statement for n). The third equality follows from Lemma 1 and the

result for ![]() .

.![]()

As an example, 6, 25, and 7 are relatively prime (in pairs). The

least common multiple is ![]() .

.

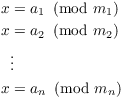

Theorem. ( The Chinese

Remainder Theorem) Suppose ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() are pairwise

relatively prime (that is,

are pairwise

relatively prime (that is, ![]() for

for ![]() ). Then the following system of congruences

has a unique solution mod

). Then the following system of congruences

has a unique solution mod ![]() :

:

Notation.

![]()

For example,

![]()

This is a convenient (and standard) notation for omitting a single

variable term in a product of things.![]()

Proof. Define

![]()

That is, ![]() is the product of the m's with

is the product of the m's with

![]() omitted. By Lemma 1,

omitted. By Lemma 1, ![]() . Hence, there are numbers

. Hence, there are numbers ![]() ,

, ![]() such that

such that

![]()

In terms of congruences,

![]()

Now let

![]()

If ![]() , then

, then ![]() , so mod

, so mod ![]() all the terms but the k-th term are 0 mod

all the terms but the k-th term are 0 mod ![]() :

:

![]()

This proves that x is a solution to the system of congruences (and incidentally, gives a formula for x).

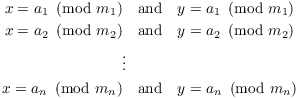

Now suppose that x and y are two solutions to the system of congruences.

Then

![]()

Thus, ![]() is a multiple of all the m's, so

is a multiple of all the m's, so

![]()

But the m's are pairwise relatively prime, so by Lemma 3,

![]()

That is, the solution to the congruences is unique mod ![]() .

.![]()

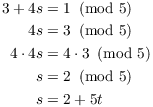

Example. Solve

![]()

![]() , so there is a unique solution

mod 36. Following the construction of x in the proof,

, so there is a unique solution

mod 36. Following the construction of x in the proof,

![]()

![]()

Solution:

![]()

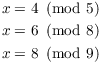

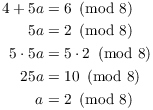

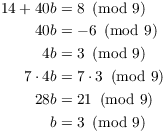

Example. Solve

The moduli are pairwise relatively prime, so there is a unique solution mod 60. This time, I'll solve the system using an iterative method.

![]()

But ![]() , so

, so

Hence,

![]()

Finally, ![]() , so

, so

Hence, ![]() .

.

Now put everything back:

![]()

Example. Calvin Butterball keeps pet meerkats in his backyard. If he divides them into 5 equal groups, 4 are left over. If he divides them into 8 equal groups, 6 are left over. If he divides them into 9 equal groups, 8 are left over. What is the smallest number of meerkats that Calvin could have?

Let x be the number of meerkats. Then

From ![]() , I get

, I get ![]() . Plugging this into the second congruence,

I get

. Plugging this into the second congruence,

I get

Hence, ![]() . Plugging this into

. Plugging this into ![]() gives

gives

![]()

Plugging this into the third congruence, I get

Hence, ![]() . Plugging this into

. Plugging this into ![]() gives

gives

![]()

The smallest positive value of x is obtained by setting ![]() , which gives

, which gives ![]() .

.![]()

You can sometimes solve a system even if the moduli aren't relatively prime; the criteria are similar to those for solving system of linear Diophantine equations.\blank

Theorem. Consider the system

![]()

(a) If ![]() , there are

no solutions.

, there are

no solutions.

(b) If ![]() , there is a

unique solution mod

, there is a

unique solution mod ![]() .

.

Note that if ![]() , case (b)

automatically holds, and

, case (b)

automatically holds, and ![]() ---

i.e. I get the Chinese Remainder Theorem for

---

i.e. I get the Chinese Remainder Theorem for ![]() .

.

Proof. (a) I'll prove the contrapositive. Suppose x is a solution to the system of congruences, so

![]()

The first congruence gives ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Similarly,

. Similarly, ![]() . But

. But ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so

![]()

Therefore,

![]()

This proves the contrapositive of the assertion, so (a) is true.

(b) First, suppose that if x and y are solutions to the system.

![]()

Thus, ![]() . Similarly,

. Similarly, ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is a multiple of

is a multiple of ![]() and

and ![]() , it is a multiple of

, it is a multiple of

![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

![]()

Thus, any two solutions are congruent mod ![]() .

.

Now suppose ![]() , so

, so ![]() for some

for some ![]() . Note that

. Note that

![]()

It follows that ![]() is

invertible mod

is

invertible mod ![]() ,

so there is an integer p such that

,

so there is an integer p such that

![]()

I claim that the following is a solution to the system for all ![]() :

:

![]()

You can obtain this "guess" by working backwards from the system assuming there is a solution, and solving the congruences by basic algebra. I will omit the details.

First, since ![]() ,

,

![]()

This shows that the proposed solution satisfies the first congruence.

Next. I need to reduce ![]() mod

mod ![]() and show that I get

and show that I get

![]() . I'll need the following facts. First,

since

. I'll need the following facts. First,

since ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() .

.

Second, since ![]() , we have

, we have

![]()

Hence,

![]()

![]()

![]()

This shows that ![]() solves the congruences for all

solves the congruences for all ![]() --- and so

--- and so ![]() is a solution mod

is a solution mod ![]() . Our initial observation shows that this

is the only solution mod

. Our initial observation shows that this

is the only solution mod ![]() .

.![]()

Let's look at an example to show how this works. Suppose we have the system of congruences

![]()

We have ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , the condition for a

solution is satisfied.

, the condition for a

solution is satisfied.

First, ![]() .

.

Next,

![]()

The multiplicative inverse of 6 mod 7 is ![]() . (You can find this by trial and error, or

using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm.) A solution mod

. (You can find this by trial and error, or

using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm.) A solution mod ![]() is

is

![]()

You can check that 141 solves the original congruences.

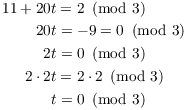

Example. Solve

![]()

Since ![]() , there is a unique

solution mod

, there is a unique

solution mod ![]() . I'll use the

iterative method to find the solution.

. I'll use the

iterative method to find the solution.

![]()

Since ![]() ,

,

![]()

Now I use my rule for "dividing" congruences: 6 divides

both 12 and 6, and ![]() , so I can

divide through by 6:

, so I can

divide through by 6:

![]()

Multiply by 2, and convert the congruence to an equation:

![]()

Plug back in:

![]()

Copyright 2022 by Bruce Ikenaga