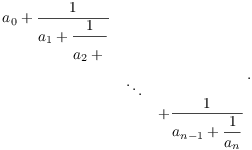

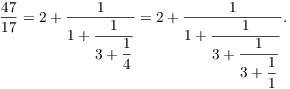

Definition. Let ![]() , ...

, ... ![]() be real numbers, with

be real numbers, with

![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() positive. A finite continued

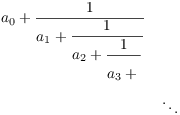

fraction is an expression of the form

positive. A finite continued

fraction is an expression of the form

To make the writing easier, I'll denote the continued fraction above

by ![]() . In most cases,

the

. In most cases,

the ![]() 's will be integers.

's will be integers.

Remark. In some cases people have considered continued fractions where the numerators don't have to be 1. For example,

In this case, they refer to continued fractions where the numerators are all 1 as simple continued fractions.

I will only be considering continued fractions where the numerators are all 1. So to save writing, I won't use the adjective "simple", and use the phrase "continued fraction" to mean a continued fraction with numerators all eqaul to 1.

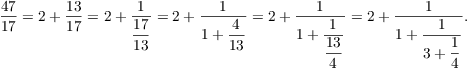

Example. Find a continued fraction expansion

for ![]() .

.

I can do this by repeated division:

In short form, ![]() .

.

Now repeated division is what you do in executing the Euclidean algorithm and so a little bit of thought should convince you that you can express any rational number as a finite continued fraction in this way. Specifically,

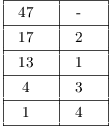

Notice that the successive quotients 2, 1, 3, and 4 are the numbers

in the continued fraction expansion.![]()

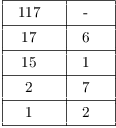

Example. Find a finite continued fraction

expansion for ![]() .

.

![$$\dfrac{117}{17} = [6; 1, 7, 2] = 6 + \dfrac{1}{1 + \dfrac{1}{7 + \dfrac{1}{2}}}.\quad\halmos$$](finite-continued-fractions15.png)

I have been asking for a finite continued fraction expansion, not the finite continued fraction expansion. In fact, the continued fraction expansion of a rational number is not unique. For example,

And in general,

![]()

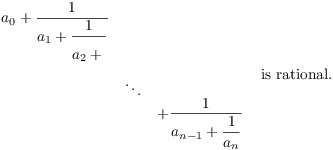

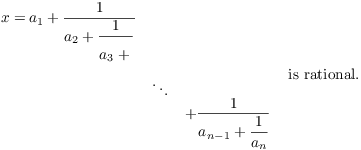

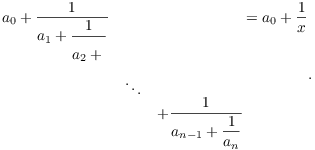

Lemma. Every finite continued fraction with integer terms represents a rational number.

Proof. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() is rational.

is rational.

Inductively, suppose that a finite continued fraction with ![]() "levels" is a rational number. I

want to show that

"levels" is a rational number. I

want to show that

By induction,

So

This is the sum of two rational numbers, which is rational as

well.![]()

I'd like eventually to discuss infinite continued fractions --- things that look like

In preparation for this, I'll look at the effect of truncating a continued fraction.

Definition. The ![]() convergent of the

continued fraction

convergent of the

continued fraction ![]() is

is

![]()

Note that for ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

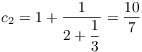

Example. Find the first four convergents of

![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

And ![]() as

well.

as

well.![]()

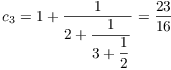

It is tedious to have to compute convergents by doing the algebra to

simplify an enormous fraction. The next result gives an algorithm for

computing the convergents of a continued fraction. It's important for

theoretical reasons, too --- I'll need it for several of the proofs

that follow. For the theorem, I won't assume that the ![]() 's are integers, since I will need the general result

later on.

's are integers, since I will need the general result

later on.

Theorem. Let ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() . Let

. Let

![]()

![]()

![]()

Then the k-th convergent of ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Proof. First, note that

![$$\raise0.61in\hbox{$[b_0; b_1, \ldots, b_k, b_{k + 1}] =$} \matrix{b_0 + \dfrac{1}{b_1 + \dfrac{1}{b_2 + \vphantom{\dfrac{1}{b_3}}}} & & \cr & \ddots & \cr & & + \dfrac{1}{b_{k - 1} + \dfrac{1}{b_k + \dfrac{1}{b_{k + 1}}}} \cr} \raise0.61in\hbox{$= \left[b_0; b_1, \ldots, b_k + \dfrac{1}{b_{k + 1}}\right]$}.$$](finite-continued-fractions45.png)

I got this by regarding the last two terms as a single term.

Note also that ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() and

and ![]() , ...,

, ..., ![]() are the same for

these two fractions, since they only differ in the k-th term.

are the same for

these two fractions, since they only differ in the k-th term.

Now I'll start the proof --- it will go by induction on k. For ![]() ,

,

![]()

And for ![]() ,

,

![]()

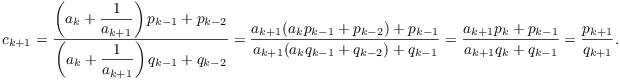

Suppose ![]() , and assume that result holds

through the k-th convergent. Then

, and assume that result holds

through the k-th convergent. Then

![]()

Now this is the k-th convergent of a continued fraction, so by

induction this is ![]() , where

, where

![]() and

and ![]() refer to

refer to ![]() (as opposed to

(as opposed to ![]() ). But what are the

). But what are the

![]() and

and ![]() for this fraction? They're given inductively by

for this fraction? They're given inductively by

![]()

Now ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are the same for

are the same for ![]() and

and ![]() , as I noted at the start. On the other hand, the

k-th term of

, as I noted at the start. On the other hand, the

k-th term of ![]() is

is ![]() . So

. So

(The next to the last equality also follows by induction.) This shows

that the result holds for ![]() , so the induction

step is complete.

, so the induction

step is complete.![]()

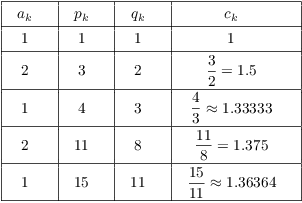

Example. Compute ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

There is a pattern to the computation of the p's and q's which makes things pretty easy. To get the next p, for instance, multiply the current a by the last p and add the next-to-the-last p.

Notice that in the last example, the convergents oscillate, and that the fractions which give the convergents are always in lowest terms. We'll see that this holds in general.

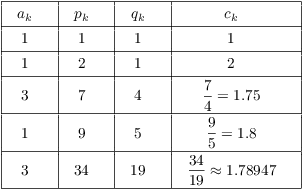

Example. Find ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

Again, notice that the convergents oscillate, and that the fractions

for the convergents are always in lowest terms.![]()

I'll prove that the convergent fractions are in lowest terms first.

Theorem. Let ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() . Let

. Let

![]()

![]()

![]()

Then

![]()

Proof. I'll induct on k. For ![]() ,

,

![]()

Take ![]() , and assume the result holds for

k. Then

, and assume the result holds for

k. Then

![]()

![]()

This proves the result for ![]() , so the general result is true by

induction.

, so the general result is true by

induction. ![]()

Corollary. Let ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() . Let

. Let

![]()

![]()

![]()

Then ![]() is in

lowest terms for

is in

lowest terms for ![]() .

.

Proof. ![]() implies that

implies that ![]() .

.![]()

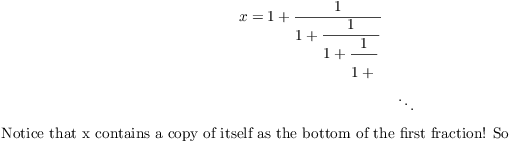

Example. The Golden Ratio ![]() has the

infinite continued fraction expansion

has the

infinite continued fraction expansion ![]() .

.

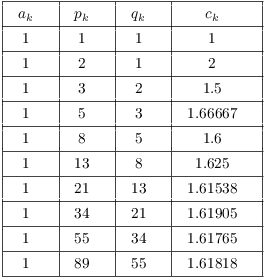

(a) Find the first 10 convergents.

(b) Find an integer linear combination of 89 and 55 that is equal to 1.

(a)

(You might have noticed that the p's and q's are the Fibonacci numbers!)

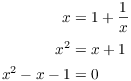

In fact, ![]() . In this case, you can see formally that

. In this case, you can see formally that ![]() should be

should be ![]() . Let

. Let

The roots are ![]() . Since the fraction is positive, take the positive root to obtain

. Since the fraction is positive, take the positive root to obtain

![]() .

.![]()

(b) Applying the Theorem to the last two rows of the table, I have

![]()

Copyright 2022 by Bruce Ikenaga